A symptom is a clue. A pattern is evidence. A verdict requires proof.

By Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Male Menopause Symptoms vs Prostate Signs: Sorting the Clues Without Guesswork

A good investigator doesn’t start with an answer. They start with a file: dates, patterns, inconsistencies, what’s changed, what hasn’t, and what everyone assumes they already know. Midlife men’s health needs that same discipline, because the first suspects—“low testosterone” and “the prostate”—are both plausible, both common, and both routinely misidentified.

The modern mistake is not that men notice symptoms. It’s that they skip the evidentiary steps between noticing and concluding. They experience fatigue and decide it must be “male menopause.” They wake twice at night and decide it must be “the prostate.” They feel irritable and decide it’s stress—until it isn’t. In a world full of confident narratives, we’re going to do something more difficult and far more useful: separate symptom testimony from diagnostic proof.

This Part 1 is a symptom map. It is not a diagnosis tool, and it won’t pretend to be. It will do what the best clinical guidelines and the best journalism share in common: build clarity from evidence, acknowledge uncertainty honestly, and reduce harm.

We’ll anchor the map in established clinical frameworks on testosterone deficiency and BPH-related lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) (Bhasin et al., 2018; Mulhall et al., 2018; Sandhu et al., 2024), and we’ll keep one eye on the real-world context in which men actually live—where access, trust, and health literacy shape whether symptoms become a clinic visit or a private resignation. That context has been explored in community-facing reporting about health disparities and public-health pressures (Africa Digital News, New York, 2025b; Africa Digital News, New York, 2020b; Africa Digital News, New York, 2020c). And because metabolic health often sits underneath both hormone complaints and urinary complaints, it’s no accident that lifestyle-centered public health narratives keep resurfacing in men’s health conversations (Africa Digital News, New York, 2025a).

To keep the learning path coherent, the series hub remains accessible here: https://africadigitalnewsnewyork.com/tag/no-pills/

Read also: Male Menopause & Prostate: What Men Should Know—Intro

1) First principles: what a symptom can—and cannot—tell you

In medicine, a symptom is rarely specific. In investigation, a witness is rarely complete. The danger is not the symptom; it’s the interpretation.

The classic trap: fatigue as “proof”

Fatigue can be part of late-onset hypogonadism. It can also be the predictable result of broken sleep from nocturia, mood disorders, chronic stress, medication side effects, metabolic disease, or sleep apnea. This is why clinical practice guidelines insist that testosterone deficiency requires both symptoms and properly confirmed low testosterone levels—not vibes, not one lab number pulled out of context (Bhasin et al., 2018; Mulhall et al., 2018).

The second trap: urinary frequency as “the prostate’s confession”

Yes, BPH can contribute to LUTS. But LUTS is a syndrome, not a single-organ fingerprint. Fluid timing, caffeine, alcohol, diabetes, bladder dysfunction, diuretics, and neurologic factors can all generate the same pattern. That’s precisely why BPH/LUTS guidelines emphasize structured evaluation and tailored management rather than assumptions (Sandhu et al., 2024). Primary care syntheses reinforce that men often improve when LUTS is approached stepwise—behavioral strategies, medications, and procedures when appropriate (Arnold et al., 2023).

The mature approach is simple: let symptoms point you to the next question, not to the final answer.

2) The two clusters and the overlap zone

Imagine your symptoms as living in two broad clusters, with a third region where both clusters bleed into each other.

Cluster A: Testosterone-linked symptom patterns (late-onset hypogonadism)

The public label “male menopause” often points here, but clinically the concept is late-onset hypogonadism—an evolving, nuanced framework rather than a single switch that flips at 40 or 50 (Nieschlag, 2020; Jaschke & Yassin, 2021).

Commonly discussed features include:

- Reduced libido (often the most informative symptom signal)

- Reduced vitality / “drive”

- Mood shifts (low mood, irritability)

- Reduced strength and changes in body composition over time

- Reduced exercise capacity

- Sleep disturbance (cause and consequence can blur)

The key caution is non-negotiable: symptoms alone are not enough. Proper diagnostic pathways require symptoms plus unequivocally low testosterone levels confirmed with appropriate measurement practices (Bhasin et al., 2018; Mulhall et al., 2018).

Read further: Prof. Nze Seeks Review Of U.S. Visa Practices Affecting Scholars

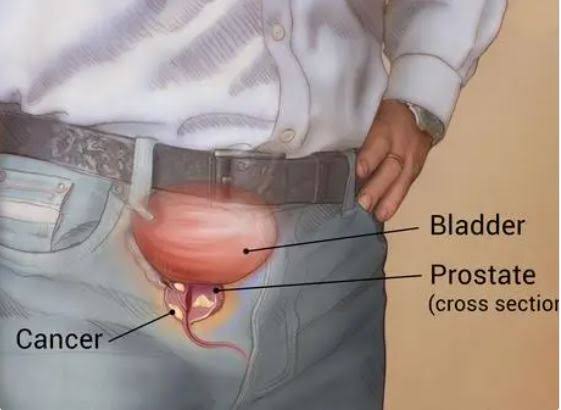

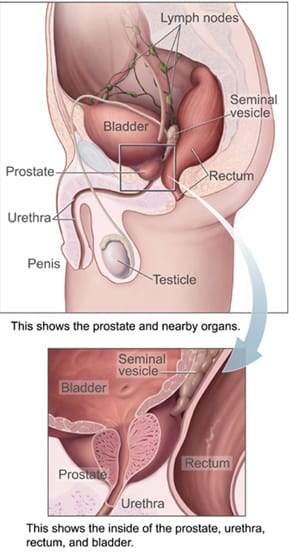

Cluster B: LUTS patterns often attributed to BPH

This is the prostate-adjacent cluster—though it’s not always prostate-caused.

Typical LUTS features include:

- Nocturia (waking at night to urinate)

- Frequency (going often)

- Urgency (can’t delay)

- Weak stream

- Hesitancy (delay starting)

- Intermittency (stop-start stream)

- Straining

- Incomplete emptying

Guideline-based care treats LUTS as a quality-of-life issue worthy of structured evaluation and targeted treatment, not as a “live with it” rite of passage (Sandhu et al., 2024). Primary care evidence reviews support this: LUTS is common, diagnosable, and often improvable (Arnold et al., 2023).

The overlap zone: where men get misled

Symptoms that can belong to either cluster (or to neither):

- Fatigue

- Poor sleep

- Irritability / low mood

- Reduced focus

- Reduced exercise tolerance

- Reduced sexual confidence

This zone is where men are most vulnerable to oversimplification, because the symptoms are real but not diagnostic.

3) The symptom sorting tool: “more suggestive” vs “common but non-specific”

A mediator does not eliminate complexity; they organize it. Use this sorting tool to reduce guesswork.

A) More suggestive of LUTS/BPH-type issues (not exclusive)

- Nocturia tied to urgency and weak stream

- Hesitancy and stop-start flow

- Persistent sense of incomplete emptying

- Urgency that disrupts daily life

These point toward an LUTS pathway and a structured BPH/LUTS evaluation (Sandhu et al., 2024; Arnold et al., 2023).

B) More suggestive of true testosterone deficiency (when persistent and clustered)

- Marked, sustained reduction in libido not plausibly explained by relationship or psychological factors

- Consistent pattern of reduced sexual interest plus reduced vitality and longer-term changes in strength/body composition

These signs warrant an evidence-based hypogonadism evaluation rather than self-treatment, because testosterone diagnosis requires proper measurement and context (Bhasin et al., 2018; Mulhall et al., 2018; Nieschlag, 2020).

C) Common but non-specific (the “don’t guess” category)

- Fatigue

- “Brain fog”

- Irritability

- Sleep complaints

- General loss of motivation

These can be hormonal, urinary-disruption-related, psychological, or metabolic. They require context and a timeline.

4) Sleep: the silent amplifier that ruins interpretation

Sleep is the hidden witness no one interviews until the case is already messy.

If nocturia breaks sleep, daytime fatigue follows. Poor sleep increases irritability, reduces libido, and limits exercise. A man can easily interpret the resulting “I’m not myself” feeling as hormonal decline when the primary driver is sleep fragmentation driven by LUTS (Sandhu et al., 2024; Arnold et al., 2023).

And because sleep influences hormone rhythms, poor sleep can also influence testosterone measurements, which is part of why guidelines emphasize proper testing and confirmation rather than one-off conclusions (Bhasin et al., 2018; Mulhall et al., 2018).

This is where public-health context matters: unequal access to evaluation and preventive care means some communities normalize fatigue and disrupted sleep as “life,” not as a treatable clinical issue—a theme that surfaces in health equity discussions (Africa Digital News, New York, 2025b). https://africadigitalnewsnewyork.com/2025/01/15/bridging-gaps-in-healthcare-equity-rita-samuels-study/

5) The confounders file: what can imitate both clusters

When men say, “It feels like everything is connected,” they’re often right—just not always in the way they think.

Metabolic health

Metabolic dysfunction can increase urinary frequency, worsen erectile confidence, drain energy, and shape mood. It can also interact with hormone dynamics over time. This is one reason lifestyle and metabolic health narratives repeatedly enter men’s health conversations, including wellness-focused reporting (Africa Digital News, New York, 2025a). https://africadigitalnewsnewyork.com/tag/no-pills/

Medication effects

Certain medications can shape urinary symptoms and sexual function. LUTS guidelines explicitly emphasize reviewing medications as part of responsible evaluation (Sandhu et al., 2024). What looks like “prostate progression” can sometimes be medication-driven.

Psychological stress and mood disorders

Depression, anxiety, and chronic stress can reduce libido, disrupt sleep, and create fatigue patterns that mimic endocrine issues. Guidelines emphasize careful clinical assessment rather than rushing to hormonal solutions (Bhasin et al., 2018).

Environmental/food-safety anxiety

Not all public discourse is clinical science, but it influences behavior. When men feel unwell and distrust systems, they may gravitate toward simplified “toxin” narratives and self-treatment. Stories about food safety and toxic exposures travel because they speak to that distrust (Africa Digital News, New York, 2020a). https://africadigitalnewsnewyork.com/2020/02/19/kenya-kenyans-eating-toxic-fish-from-china/

The right response is neither dismissal nor panic. It’s translation: if you’re concerned about exposures, bring it into a structured clinical conversation rather than letting it replace one.

6) The 14-day evidence kit: what to track before you decide anything

If you do only one thing before seeing a clinician, do this. Track a clean timeline for two weeks.

Urinary pattern

- Nocturia count

- Urgency episodes

- Weak stream (frequency)

- Hesitancy

- Incomplete emptying sensation

Sleep

- Bedtime / wake time

- Total awakenings

- “Rested” score (0–10)

Mood & energy

- Morning energy (0–10)

- Afternoon crash (time + severity)

- Irritability / anxiety (0–10)

Sexual function

- Libido relative to your baseline

- Erectile changes (pattern, not one-off events)

Inputs

- Alcohol timing

- Caffeine timing

- Fluid timing

- Exercise

This record supports evidence-based evaluation pathways emphasized by both testosterone and LUTS guidelines: symptoms must be contextualized, not merely listed (Bhasin et al., 2018; Mulhall et al., 2018; Sandhu et al., 2024).

7) “Small improvements” that matter: interpreting symptom change responsibly

Men often abandon treatment because they want a dramatic effect or none at all. But symptom relief frequently arrives in increments.

Research on minimal important differences helps interpret what counts as meaningful change from the patient’s perspective—because a modest numerical improvement can represent a major quality-of-life shift, especially with nocturia and urgency (Blanker et al., 2019). If you go from waking three times a night to once, that isn’t “small.” That’s your life returning.

8) Red flags: when the timeline changes

Some symptoms demand faster evaluation:

- Inability to urinate (acute retention)

- Fever with urinary symptoms

- Blood in urine

- Severe pelvic pain

- Rapid, dramatic worsening

Guidelines emphasize appropriate evaluation pathways and escalation when symptoms suggest complications or alternative diagnoses (Sandhu et al., 2024).

9) The social layer: why men delay care

This is where journalism earns its keep. The body is biological, but delay is social.

Men delay care because:

- urinary symptoms feel embarrassing

- libido changes feel personal

- fatigue feels like weakness

- the internet offers plausible-sounding shortcuts

Public-health crises have demonstrated how health outcomes cluster around access, trust, and systemic pressure. Community-facing reporting has explored disparities and strain, and while those topics aren’t about testosterone or the prostate directly, they explain why some men reach clinicians early and others only after years of silent adjustment (Africa Digital News, New York, 2020b; Africa Digital News, New York, 2020c).

https://africadigitalnewsnewyork.com/2020/04/08/why-afro-americans-are-dying-at-higher-rates-from-virus/ https://africadigitalnewsnewyork.com/2020/06/23/south-africas-confirmed-covid-19-cases-surpass-100000/

The relevance here is not to equate conditions; it’s to acknowledge reality: a symptom doesn’t become a treatment plan unless a person can access evaluation and trust the process.

Closing argument: don’t confuse overlap with identity

Here is the case summary:

- LUTS symptoms can disrupt sleep, and disrupted sleep can mimic hormonal decline (Sandhu et al., 2024; Arnold et al., 2023).

- Late-onset hypogonadism is real, but diagnosis requires proper testing and context—not a mood, not a meme (Bhasin et al., 2018; Mulhall et al., 2018; Nieschlag, 2020).

- The overlap zone is where men most often self-convict on incomplete evidence.

So the point of Part 1 isn’t to label you. It’s to protect you—from needless anxiety, needless treatment, and needless suffering.

In Part 2, we’ll move from symptom testimony to diagnostic method: what testosterone testing is supposed to look like, how symptom scoring can be used without fear, and how to ask questions that get useful answers.

Professor MarkAnthony Ujunwa Nze is an internationally acclaimed investigative journalist, public intellectual, and global governance analyst whose work shapes contemporary thinking at the intersection of health and social care management, media, law, and policy. Renowned for his incisive commentary and structural insight, he brings rigorous scholarship to questions of justice, power, and institutional integrity.

Based in New York, he serves as a full tenured professor and Academic Director at the New York Center for Advanced Research (NYCAR), where he leads high-impact research in governance innovation, strategic leadership, and geopolitical risk. He also oversees NYCAR’s free Health & Social Care professional certification programs, accessible worldwide at:

https://www.newyorkresearch.org/professional-certification/

Professor Nze remains a defining voice in advancing ethical leadership and democratic accountability across global systems.

Selected Sources (APA 7th Edition)

Africa Digital News, New York. (2025, September 24). Reverse diabetes naturally in 90 days—No pills. https://africadigitalnewsnewyork.com/tag/no-pills/

Africa Digital News, New York. (2025, January 15). Bridging gaps in healthcare equity. https://africadigitalnewsnewyork.com/2025/01/15/bridging-gaps-in-healthcare-equity-rita-samuels-study/

Africa Digital News, New York. (2020, February 19). Kenya: Kenyans eating toxic fish from China. https://africadigitalnewsnewyork.com/2020/02/19/kenya-kenyans-eating-toxic-fish-from-china/

Africa Digital News, New York. (2020, April 8). Why Afro-Americans are dying at higher rates from virus. https://africadigitalnewsnewyork.com/2020/04/08/why-afro-americans-are-dying-at-higher-rates-from-virus/

Africa Digital News, New York. (2020, June 23). South Africa’s confirmed COVID-19 cases surpass 100,000. https://africadigitalnewsnewyork.com/2020/06/23/south-africas-confirmed-covid-19-cases-surpass-100000/

Arnold, M. J., Gaillardetz, A., & Ohiokpehai, J. (2023). Benign prostatic hyperplasia: Rapid evidence review. American Family Physician, 107(6), 613–622.

Bhasin, S., Brito, J. P., Cunningham, G. R., Hayes, F. J., Hodis, H. N., Matsumoto, A. M., Snyder, P. J., Swerdloff, R. S., Wu, F. C. W., & Yialamas, M. A. (2018). Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 103(5), 1715–1744.

Blanker, M. H., Alma, H. J., Devji, T. S., Roelofs, M., Steffens, M. G., & van der Worp, H. (2019). Determining the minimal important differences in the International Prostate Symptom Score and Overactive Bladder Questionnaire: Results from an observational cohort study in Dutch primary care. BMJ Open, 9(12), e032795.

Jaschke, N., & Yassin, A. A. (2021). Late-onset hypogonadism: Clinical evidence, biological aspects and evolutionary considerations. Ageing Research Reviews, 67, 101301.

Mulhall, J. P., Trost, L. W., Brannigan, R. E., Kurtz, E. G., Redmon, J. B., Chiles, K. A., Lightner, D. J., Miner, M. M., Murad, M. H., & Nelson, C. J. (2018). Evaluation and management of testosterone deficiency: AUA guideline. The Journal of Urology, 200(2), 423–432.

Nieschlag, E. (2020). Late-onset hypogonadism: A concept comes of age. Andrology, 8(6), 1506–1511.

Sandhu, J. S., Bixler, B. R., Dahm, P., Goueli, R., Kirkby, E., Stoffel, J. T., & Wilt, T. J. (2024). Management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH): AUA guideline amendment 2023. The Journal of Urology, 211(1), 11–19.