A clear guide through hormones, prostate health, and midlife change.

By Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

At 2:17 a.m., the body doesn’t speak in medical terms. It speaks in repetition. Wake. Urge. Walk. Return. Try again. A man can live with a lot—work pressure, family demands, a stiff back after the gym—without calling it a “problem.” But sleep interrupted by the same nightly pattern is different. It rearranges everything that comes after: mood, energy, patience, libido, focus. And because the change arrives quietly, most men do what good citizens of modern masculinity have been trained to do: they minimize. They call it “aging,” as if the word itself were a diagnosis and not a placeholder.

This series begins where many men’s health stories go wrong—not because men are careless, but because the information environment is. “Male menopause” is a popular phrase with a dramatic ring. The prostate is an organ with a fearsome reputation. Between those two words, men are offered a flood of confident claims: quick fixes, miracle boosters, ominous warnings, and one-liners dressed as certainty. The average reader is left to act as their own clinician, investigator, and risk manager while trying not to panic.

Read also: Why Ending Nigeria’s Visa Ban Serves U.S. Interests—Part 7

So we’ll do something different. We’ll handle the topic the way a forensic investigator and a good mediator would: separate symptoms from conclusions, claims from evidence, and anxiety from risk. Not by stripping away the human element—quite the opposite. By giving it structure. You can follow the full series hub as it builds at https://africadigitalnewsnewyork.com/

What “male menopause” really means (and what it doesn’t)

Let’s put the phrase under oath.

Medically, “male menopause” is not a formal diagnosis. Men don’t experience a universal, abrupt transition comparable to menopause. What people often mean is late-onset hypogonadism, sometimes shortened in public conversation to “low T,” or more broadly, age-associated testosterone changes with symptoms that may or may not be attributable to testosterone itself (Nieschlag, 2020). That distinction matters because symptoms are not self-interpreting. A symptom is testimony; it requires corroboration.

The major clinical guardrail is consistent across authoritative guidance: testosterone deficiency is not diagnosed from mood alone, or fatigue alone, or one low lab result taken at a random time. It requires compatible symptoms plus unequivocally low testosterone confirmed with appropriate testing, interpreted in context (Bhasin et al., 2018; Mulhall et al., 2018; American Urological Association, 2024). The reason is not academic fussiness—it’s harm reduction. Testosterone levels fluctuate. They’re affected by sleep, acute illness, stress, caloric restriction, alcohol use, and body composition. A single number, divorced from context, can be misleading. A proper workup protects men from being treated for something they don’t have—and from missing something they do.

Even the symptom list deserves cross-examination. Late-onset hypogonadism can involve reduced libido, changes in erectile function, decreased vitality, and mood shifts, but many of these features overlap with depression, chronic stress, medication effects, and sleep disorders (Snyder, 2022; Bhasin et al., 2018). If you’re tired, irritable, and not “yourself,” testosterone is one hypothesis—not a verdict. The best clinical thinking refuses the easy narrative.

That’s why guideline commentary and updates emphasize process: diagnosis first, careful selection if therapy is considered, and monitoring as a core part of care—not an afterthought (Trost, 2024; American Urological Association, 2024). In other words: don’t confuse availability with appropriateness.

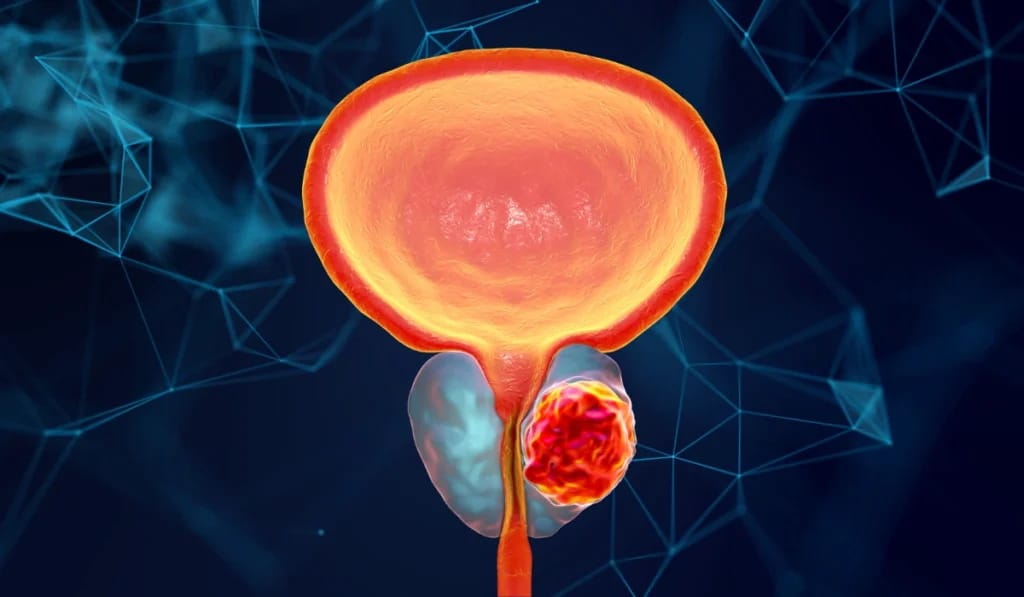

The prostate: why it changes with age

Now place the prostate on the record.

The prostate is small enough to ignore until it becomes large enough to dominate a man’s nights. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is common, increases with age, and is a leading contributor to lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS): nocturia, urgency, frequency, weak stream, hesitancy, and incomplete emptying (Sandhu et al., 2024). But LUTS is a symptom category, not a single cause. A bladder can be overactive. Sleep can be disrupted by apnea. Some medications worsen urinary issues. Metabolic health can amplify the problem. The AUA’s guideline amendment for LUTS attributed to BPH stresses structured evaluation and individualized management rather than assumptions (Sandhu et al., 2024). A rapid evidence review in primary care echoes the same point: many men can improve significantly with a stepwise plan—behavioral strategies, medication when indicated, and procedures for selected cases (Arnold et al., 2023).

Read further: Prof. Nze Seeks Review Of U.S. Visa Practices Affecting Scholars

The larger, public-health view is equally sobering. Global data show that BPH is not a niche inconvenience; it is a substantial burden across countries, rising in absolute numbers as populations age (GBD 2019 Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Collaborators, 2022). That translates into disrupted sleep at scale, reduced quality of life, and increased healthcare utilization. The reason men feel alone with it is cultural. The reason the health system feels it is epidemiological.

If the prostate story were only about urination, it might remain a private inconvenience. But it isn’t. It’s about the downstream effects: fatigue that becomes irritability, irritability that becomes isolation, isolation that becomes shame—and shame that becomes delayed care. You don’t need a pathology textbook to recognize that chain. You need honesty.

You can find the developing series index and updates here: https://africadigitalnewsnewyork.com/

The overlap: fatigue, sleep, mood, libido, urinary symptoms

This is the part that creates confusion—and where misinformation thrives.

Consider two men with the same complaint: “I’m exhausted.”

- Man Awakes three times nightly to urinate. His sleep is fragmented, and daytime fatigue follows. His mood dips. His libido fades. Exercise becomes harder. Weight creeps. He reads about “male menopause” and concludes testosterone must be the culprit. But the primary driver may be LUTS and sleep disruption (Sandhu et al., 2024; Arnold et al., 2023).

- Man Bsleeps through the night but notices a persistent drop in libido, reduced vitality, and changes in body composition. He has minimal urinary symptoms. Here, the hypothesis of testosterone deficiency deserves a structured evaluation (Snyder, 2022; Nieschlag, 2020; Mulhall et al., 2018).

These men can look identical from the outside: tired, less motivated, less engaged. Yet the underlying pathways differ. The clinical stakes are high because mislabeling the problem can lead to misdirected treatment. In forensic work, the first enemy is not malice—it’s premature certainty.

Now layer in the prostate cancer fear, because we have to. Many men hear “prostate” and immediately think “cancer.” Screening has become a public argument, but the best guidance is calmer and more precise than the shouting suggests. The USPSTF recommends individualized decision-making for PSA-based screening for many men aged 55–69, highlighting that benefits and harms are closely balanced and values matter (Grossman et al., 2018). European guidance, including the 2024 EAU prostate cancer update, situates screening and diagnosis within a structured pathway that respects both detection and overdiagnosis risks (Cornford et al., 2024). If you prefer courtroom language: PSA is not a conviction; it is a lead, and leads require corroboration.

And then, inevitably, testosterone therapy enters the conversation—and with it, louder claims than the evidence justifies. There are men for whom testosterone therapy is appropriate and beneficial, and there are men for whom it is inappropriate, risky, or simply irrelevant to their actual problem (Bhasin et al., 2018; Mulhall et al., 2018). The key is not ideology; it is selection and monitoring.

The modern evidence base is more disciplined than pop culture suggests. A major cardiovascular outcomes trial (TRAVERSE) found no significant difference in major adverse cardiovascular events between testosterone and placebo in the studied population, while underscoring that therapy should be used in appropriately selected men and monitored (Lincoff et al., 2023). In parallel, a 2024 meta-analysis reported improvements in erectile function and did not show consistent worsening of prostate-related measures in pooled analyses—again, within the context of appropriate prescribing and follow-up (Xu et al., 2024). This does not mean “testosterone is for everyone.” It means the conversation can be evidence-guided rather than fear-driven.

European urology guidance on sexual and reproductive health likewise emphasizes careful diagnosis, individualized treatment decisions, and monitoring frameworks that reflect real-world complexity (Salonia et al., 2024; Salonia et al., 2025). Across serious sources, the message is consistent: don’t rush; do it right.

What to track before you panic

Before you demand a prescription—or resign yourself to decline—collect clean information. In good investigative work, the timeline is everything. In good medicine, it’s similar: a structured symptom record often reveals what random recall hides.

Here’s a simple, practical checklist to run for 10–14 days:

1) Sleep

- Bedtime and wake time

- Number of awakenings

- “Rested?” rating (0–10)

- Snoring, choking, or witnessed pauses (if relevant)

2) Urinary pattern

- Nocturia count

- Urgency episodes (how often you feel you mustgo now)

- Weak stream or hesitancy

- Sense of incomplete emptying

3) Energy and mood

- Morning energy (0–10)

- Afternoon crash (yes/no, time)

- Irritability/anxiety/low mood (0–10)

4) Libido and sexual function

- Changes from your baseline—not compared to anyone else

- Notice pattern: is it stable, fluctuating, stress-linked?

5) Lifestyle exposures

- Alcohol timing (especially evening)

- Caffeine timing (especially afternoon/evening)

- Exercise frequency

- Meal timing (late heavy meals can worsen sleep)

This record does two things: it reduces guesswork, and it gives a clinician usable data aligned with structured evaluation approaches emphasized in guidelines (Sandhu et al., 2024; Mulhall et al., 2018).

Doctor questions to ask

A strong clinical visit is not a performance; it’s a collaboration. These questions help you convert vague suffering into actionable steps—without sounding confrontational.

If you suspect low testosterone

- “Given my symptoms, what are the most likely explanations besides testosterone?” (Snyder, 2022; Bhasin et al., 2018)

- “If we test testosterone, how should it be timed, and will we repeat it to confirm?” (Mulhall et al., 2018; American Urological Association, 2024)

- “Are sleep, weight, or medications likely suppressing testosterone?” (Bhasin et al., 2018)

- “If treatment is considered, what monitoring plan will we follow?” (Trost, 2024; American Urological Association, 2024)

If urinary symptoms are prominent

- “Do my symptoms fit typical BPH/LUTS, or might bladder or medication factors be contributing?” (Sandhu et al., 2024; Arnold et al., 2023)

- “What behavioral changes can reduce nocturia and urgency before medication?” (Sandhu et al., 2024)

- “If medication is indicated, what benefits and side effects should I expect?” (Arnold et al., 2023)

If screening anxiety is driving decisions

- “How do my age and risk profile shape whether screening makes sense?” (Grossman et al., 2018; Cornford et al., 2024)

- “If PSA is elevated, what are the next steps before we jump to conclusions?” (Cornford et al., 2024)

Test list: what commonly enters the conversation

This is an introduction, not a medical directive—but it helps to know what clinicians commonly consider.

- Testosterone evaluationoften starts with properly timed testing and confirmation when needed, interpreted alongside symptoms and potential confounders (Mulhall et al., 2018; Bhasin et al., 2018; American Urological Association, 2024).

- LUTS/BPH evaluationprioritizes symptom characterization, risk assessment, and stepwise management (Sandhu et al., 2024; Arnold et al., 2023).

- Prostate cancer screening conversationsshould reflect shared decision-making frameworks and guideline structure (Grossman et al., 2018; Cornford et al., 2024).

What matters most is not memorizing test names. It’s understanding that competent care follows a sequence: evaluate, interpret, then act—rather than act and backfill an explanation.

Food and habits: the quiet levers

No serious introduction promises that diet “fixes” hormones or prostate issues outright. But it would be equally irresponsible to ignore that sleep quality, metabolic health, alcohol timing, and activity levels can intensify both hormone-related symptoms and urinary symptoms. Guidance on testosterone therapy repeatedly emphasizes context: obesity, sleep disruption, and systemic illness can influence testosterone levels and symptom expression (Bhasin et al., 2018; Snyder, 2022). And LUTS management frameworks routinely include behavioral strategies alongside medication when appropriate (Sandhu et al., 2024). Think of lifestyle as signal control: reduce the noise, and the real problem becomes easier to identify.

Where we go from here

The intro has one job: to replace fog with a map. The map is not a diagnosis; it is a method. The method is simple and serious: track patterns, test appropriately, and make decisions with evidence rather than pressure.

In Part 1, we open the symptom file properly. We’ll sort which symptoms more strongly suggest hypogonadism, which more strongly suggest LUTS/BPH, which overlap, and which demand urgent evaluation—using the same evidence base cited here (Sandhu et al., 2024; Snyder, 2022; Mulhall et al., 2018; Grossman et al., 2018). Because the real scandal in midlife men’s health is not that bodies change. It’s that too many men are left alone with the wrong explanations—until the avoidable becomes urgent.

The ongoing series hub remains here: https://africadigitalnewsnewyork.com/

Professor MarkAnthony Ujunwa Nze is an internationally acclaimed investigative journalist, public intellectual, and global governance analyst whose work shapes contemporary thinking at the intersection of health and social care management, media, law, and policy. Renowned for his incisive commentary and structural insight, he brings rigorous scholarship to questions of justice, power, and institutional integrity.

Based in New York, he serves as a full tenured professor and Academic Director at the New York Center for Advanced Research (NYCAR), where he leads high-impact research in governance innovation, strategic leadership, and geopolitical risk. He also oversees NYCAR’s free Health & Social Care professional certification programs, accessible worldwide at:

https://www.newyorkresearch.org/professional-certification/

Professor Nze remains a defining voice in advancing ethical leadership and democratic accountability across global systems.

Selected Sources (APA 7th Edition)

Africa Digital News, New York. (n.d.). Africa Digital News, New York. https://africadigitalnewsnewyork.com/

American Urological Association. (2024). Testosterone deficiency guideline.

Arnold, M. J., Gaillardetz, A., & Ohiokpehai, J. (2023). Benign prostatic hyperplasia: Rapid evidence review. American Family Physician, 107(6), 613–622.

Bhasin, S., Brito, J. P., Cunningham, G. R., Hayes, F. J., Hodis, H. N., Matsumoto, A. M., Snyder, P. J., Swerdloff, R. S., Wu, F. C. W., & Yialamas, M. A. (2018). Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 103(5), 1715–1744.

Cornford, P., van den Bergh, R. C. N., Briers, E., Van den Broeck, T., Brunckhorst, O., Darraugh, J., Eberli, D., De Meerleer, G., De Santis, M., Farolfi, A., Gandaglia, G., Gillessen, S., Grivas, N., Henry, A. M., Lardas, M., van Leenders, G. J. L. H., Liew, M., Linares Espinós, E., Oldenburg, J., … Tilki, D. (2024). EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer—2024 update. Part I: Screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. European Urology, 86(2), 148–163.

GBD 2019 Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Collaborators. (2022). The global, regional, and national burden of benign prostatic hyperplasia in 204 countries and territories from 2000 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Healthy Longevity, 3(11), e754–e776.

Grossman, D. C., Curry, S. J., Owens, D. K., Bibbins-Domingo, K., Caughey, A. B., Davidson, K. W., Doubeni, C. A., Ebell, M., Epling, J. W., Jr., Kemper, A. R., Krist, A. H., Kubik, M., Landefeld, C. S., Mangione, C. M., Phipps, M. G., Silverstein, M., Simon, M. A., Tseng, C.-W., & US Preventive Services Task Force. (2018). Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA, 319(18), 1901–1913.

Lincoff, A. M., Nissen, S. E., & TRAVERSE Investigators. (2023). Cardiovascular safety of testosterone-replacement therapy. The New England Journal of Medicine, 389(2), 107–117.

Mulhall, J. P., Trost, L. W., Brannigan, R. E., Kurtz, E. G., Redmon, J. B., Chiles, K. A., Lightner, D. J., Miner, M. M., Murad, M. H., & Nelson, C. J. (2018). Evaluation and management of testosterone deficiency: AUA guideline. The Journal of Urology, 200(2), 423–432.

Nieschlag, E. (2020). Late-onset hypogonadism: A concept comes of age. Andrology, 8(6), 1506–1511.

Salonia, A., Bettocchi, C., Boeri, L., Capogrosso, P., Carvalho, J., Corona, G., … Minhas, S. (2024). EAU guidelines on sexual and reproductive health (2024). European Association of Urology.

Salonia, A., Capogrosso, P., Boeri, L., Cocci, A., Corona, G., Dinkelman-Smit, M., Falcone, M., Jensen, C. F., Gül, M., Kalkanli, A., Kadioğlu, A., Martinez-Salamanca, J. I., Morgado, L. A., Russo, G. I., Serefoğlu, E. C., Verze, P., & Minhas, S. (2025). European Association of Urology guidelines on male sexual and reproductive health: 2025 update on male hypogonadism, erectile dysfunction, premature ejaculation, and Peyronie’s disease. European Urology, 88(1), 76–102.

Sandhu, J. S., Bixler, B. R., Dahm, P., Goueli, R., Kirkby, E., Stoffel, J. T., & Wilt, T. J. (2024). Management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH): AUA guideline amendment 2023. The Journal of Urology, 211(1), 11–19.

Snyder, P. J. (2022). Symptoms of late-onset hypogonadism in men. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, 51(4), 755–760.

Trost, L. (2024). Update to the testosterone guideline. The Journal of Urology, 211(4), 608–610.

Xu, Z., Chen, X., Zhou, H., Ren, C., Wang, Q., Pan, Y., Liu, L., & Liu, X. (2024). An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of testosterone replacement therapy on erectile function and prostate. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 15, 1335146.