“This work traces that architecture — from the hidden wells of power where contracts are traded in silence, to the offshore vaults where public wealth vanishes behind shell companies and numbered accounts. It follows the money, but more importantly, it follows the silence: the journalists jailed, the whistleblowers silenced, the citizens excluded.”

By Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Investigative Journalist | Public Intellectual | Global Governance Analyst | Health & Social Care Expert | International Business/Immigration Law Professional |Strategic & Management Economist

Editorial Summary

The Oil Block Mafia: Africa’s Untold Story is a sweeping exposé of how Africa’s greatest promise—its oil wealth—became its most enduring tragedy. Across twelve meticulously argued parts, it traces the architecture of corruption that has transformed the continent’s natural riches into private empires, revealing how power, secrecy, and global complicity conspired to turn abundance into inequality.

Beginning with the opaque allocation of oil blocks, the series exposes the origins of a shadow economy built on patronage and plunder. It reveals how political elites, foreign corporations, and financial enablers engineered a system where contracts are currency, and public office is the shortest route to private wealth. Each part dissects a different layer of this machinery—from the creation of shell companies and offshore havens to the capture of politics, the silencing of dissent, and the erosion of accountability.

The investigation paints a portrait of the “Oil Block Mafia”—not a cabal of villains, but a self-sustaining network of officials, traders, and intermediaries whose power transcends borders and regimes. It follows the money trail through boardrooms, offshore registries, and tax havens, showing how Africa’s lost billions reappear as luxury assets abroad. The narrative expands beyond national borders, indicting the global financial system that launders corruption behind the façade of legality.

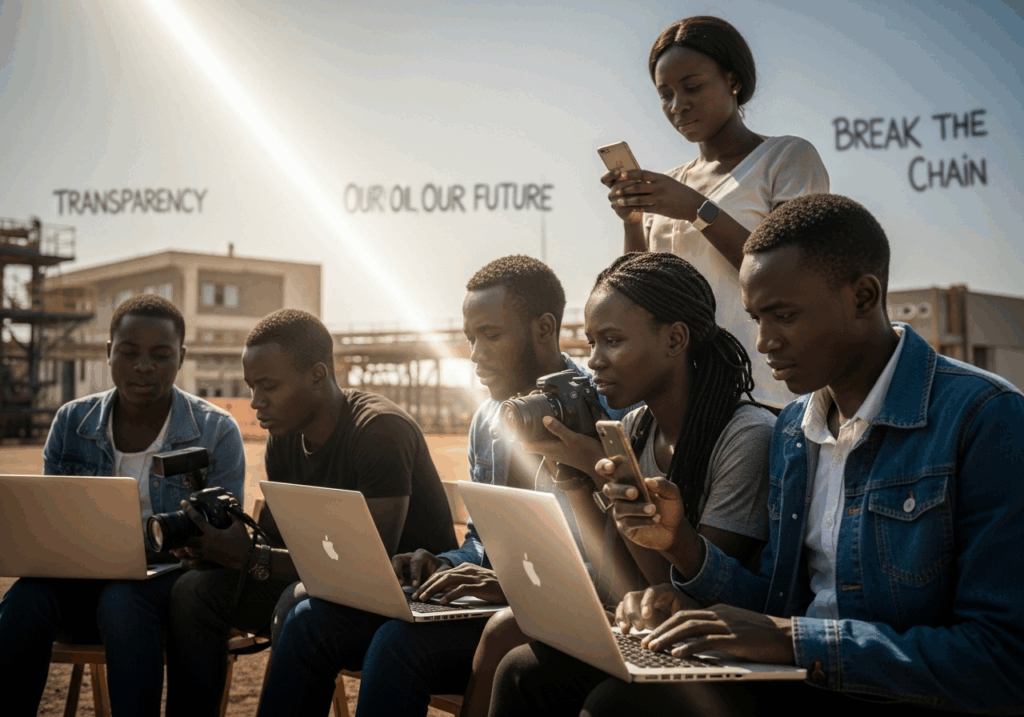

Yet The Oil Block Mafia is more than an autopsy of failure; it is a chronicle of resistance. It documents the rise of reformers—journalists, auditors, activists, and technocrats—who are prying open the once-sealed world of extractive governance. From the EITI’s strengthened anti-corruption standards to the Opening Extractives partnership and citizen data-tracking movements like BudgIT and Connected Development, the work highlights how transparency is emerging as Africa’s new form of sovereignty.

The exposé culminates in The Reckoning, a call for moral and institutional renewal. It argues that Africa’s redemption lies not merely in recovering stolen wealth, but in rebuilding the ethical foundations of governance. The oil curse, it concludes, was never inevitable—it was designed. And because it was designed, it can be undone.

A work of piercing intellect and moral gravity, it dismantles the convenient fiction that Africa’s corruption is cultural inevitability rather than a carefully engineered inheritance. Beneath its forensic gaze, the architecture of plunder is revealed—not as chaos, but as design; not as fate, but as authorship. It traces how systems became syndicates, how governance was hollowed into theater, and how silence became a global currency. Yet, within this unflinching exposé lies a fierce faith in restoration. It insists that corruption is not the continent’s soul but its script—and scripts can be rewritten. This is more than an account of power’s abuses; it is an invocation for moral insurgency, a reminder that reclamation begins where resignation ends.

Part 1: The Hidden Wells of Power

Where Africa’s oil wealth begins—and where transparency ends.

Africa’s oil wealth lies buried not only beneath its soil but deep within the corridors of bureaucracy, secrecy, and influence. Long before a single barrel is drilled or shipped abroad, the fate of billions is decided in quiet offices—where oil blocks are traded like currency among the powerful. Here, within these hidden wells of power, Africa’s resource wealth becomes the private property of the few, long before it can ever belong to the many.

The story of oil in Africa begins, paradoxically, with hope. When global commodity prices soared in the early 2000s, many African nations, from Nigeria to Angola to Ghana, saw their oil reserves as the ticket to transformation. New wealth promised schools, roads, jobs, and energy security. But what followed was a familiar pattern: optimism drowned in the murky waters of corruption, mismanagement, and elite capture.

Across the continent, the process of allocating oil blocks—the licenses that determine who explores and extracts crude—has become one of the least transparent stages in the resource chain. It is here that the true architecture of corruption takes shape. The moment an oil block is “awarded,” wealth and influence shift hands. The winners are rarely technocrats or companies with proven expertise; they are insiders—politically connected firms, family members of government officials, and shell companies registered in faraway tax havens. The losers are the citizens, watching from the margins of an industry that was meant to lift them out of poverty.

Despite years of reform efforts, including the push for contract transparency, the basic equation remains unchanged: access to oil means access to power, and power means control over information. Licensing rounds are often announced with grand rhetoric about openness and competition, yet the details—who bids, who wins, and on what terms—are obscured behind legal technicalities and bureaucratic smokescreens.

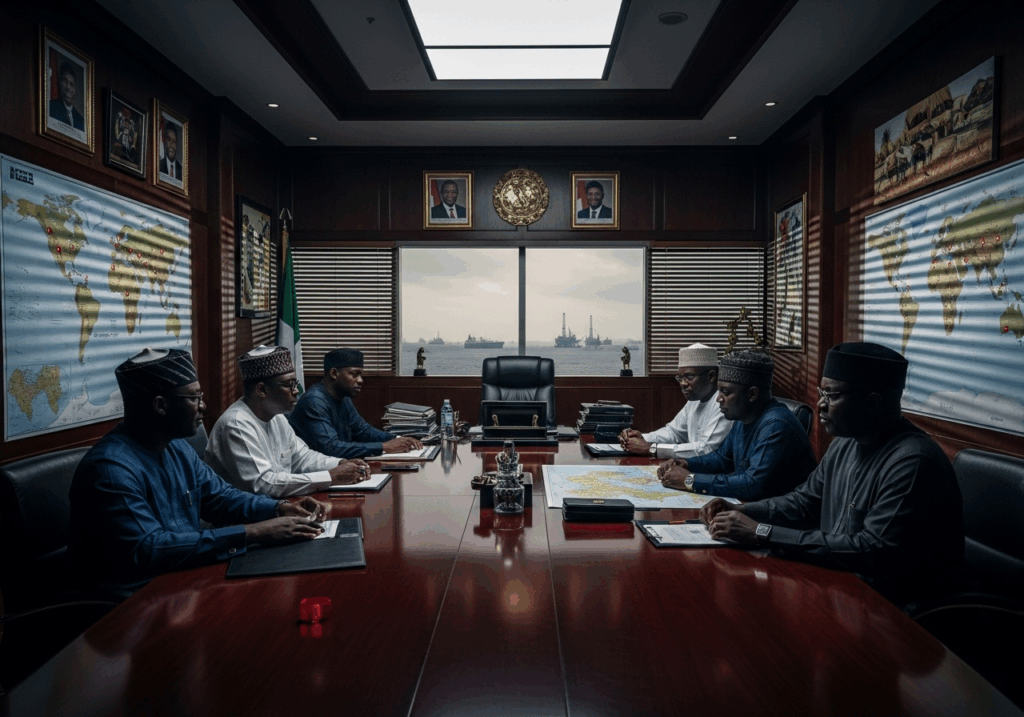

Take, for example, the modern spectacle of oil block licensing. Governments announce tenders, inviting both domestic and international companies to compete. But beneath the surface, decisions are often predetermined. Political loyalists and campaign financiers are quietly rewarded, sometimes through “joint ventures” that disguise patronage as partnership. By the time official results are published, the true dealmaking has already happened—in backrooms, over phone calls, or during quiet visits to ministerial homes in Abuja, Luanda, or Accra.

This entrenched secrecy is not accidental; it is a design perfected over decades. The allocation of oil blocks is not merely an administrative exercise—it is the lifeblood of patronage systems that keep political elites entrenched. In Nigeria, for instance, oil block awards have historically served as both political reward and financial weapon. They fund election campaigns, sustain loyalty networks, and silence dissent. In Angola, the pattern is similar: oil concessions are a mechanism for wealth transfer from the state to a narrow circle of elites. Across borders, the playbook rarely changes—only the actors do.

The real victims of this opacity are the citizens who never see the contracts that determine the value of their national assets. Without access to those agreements, there can be no accountability for how much a company pays, how much the state receives, or how the money is spent. In theory, transparency initiatives have made some headway in forcing disclosures. In practice, many governments release partial data or bury key details under dense bureaucratic language. The result is a system that appears compliant but remains fundamentally opaque.

Behind every opaque contract lies an economic consequence. Billions of dollars in potential revenue vanish into legal loopholes, inflated consultancy fees, and “signature bonuses” that are quietly redistributed among political allies. The public is told the deals were struck “in the national interest,” yet the national accounts tell a different story—one of missing funds, stalled projects, and ghost revenues. When oil prices crash, it is ordinary citizens who bear the brunt, while those who profited from the licensing windfalls retreat behind layers of legal immunity and offshore anonymity.

The struggle for transparency, though persistent, remains an uphill battle. International frameworks such as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) were designed to shine light into this darkness. They advocate for open contracts, full disclosure of ownership structures, and clear reporting of payments between governments and companies. Yet in many African states, compliance is treated as a box-ticking exercise rather than a transformative commitment. Reports are filed, workshops are held, and committees are formed—but the core question remains unanswered: who truly owns the oil blocks?

Ownership, in this context, is not simply about paperwork—it is about sovereignty. When the true beneficiaries of oil licenses are hidden behind shell companies registered in foreign jurisdictions, African nations effectively lose control of their own natural wealth. The oil may be in Nigerian waters or Angolan soil, but the profits flow to bank accounts in London, Dubai, or Zurich. What is left behind is environmental ruin, fiscal instability, and citizens who are told that prosperity is just one oil discovery away.

The moral dimension of this crisis cannot be ignored. Every secret deal erodes public trust; every opaque contract deepens inequality. Citizens, disillusioned by decades of unfulfilled promises, no longer believe in the rhetoric of reform. They see new licensing rounds not as opportunities for progress, but as fresh rounds of plunder. When oil blocks are sold under the guise of development, and revenues vanish into private pockets, democracy itself is weakened. The link between the state and its citizens becomes transactional, defined not by representation but by exploitation.

At the same time, global demand for energy continues to evolve. As the world transitions toward renewables, Africa faces the paradox of abundance and irrelevance. The continent holds vast reserves of oil and gas that could still power economies—but if corruption and secrecy persist, those resources will only entrench inequality rather than bridge it. The race for transparency is not just about moral accountability; it is about survival in a changing global economy.

Yet hope, though fragile, is not extinct. In recent years, investigative journalists, civil society groups, and reform-minded bureaucrats have begun to expose the hidden architecture of oil governance. Leaked documents, whistleblower testimonies, and forensic audits are slowly revealing how billions have been siphoned away. These efforts are not without risk—many who challenge the oil establishment face intimidation, censorship, or worse—but they represent the first cracks in the walls of secrecy that have long protected the oil elite.

To understand Africa’s oil politics, one must therefore start at the beginning—not in the refineries, not at the export terminals, but at the moment of allocation. It is in that single bureaucratic act, the awarding of an oil block, that the future of a nation’s economy can be decided. Transparency at that stage is not optional; it is existential. For without it, oil ceases to be a blessing. It becomes a weapon of control—a resource not for development, but domination.

The hidden wells of power run deep, winding through ministries, offshore banks, and corporate boardrooms. They connect the fate of nations to the greed of individuals. Until those wells are drained of secrecy, Africa’s oil story will remain one of paradox—rich lands, poor people; booming exports, bankrupt states; public wealth, private empires.

The challenge, therefore, is not just to expose these hidden networks but to dismantle them—to make transparency the default rather than the exception. It requires political courage, global accountability, and an informed citizenry that demands more than promises. For as long as the wells remain hidden, the dream of shared prosperity will remain just that—a dream buried beneath the surface of Africa’s most valuable resource.

Part 2: Birth of the Oil Block Mafia

From public servants to private tycoons—the making of Africa’s oil cartel.

Every empire begins with a secret. Africa’s oil empire was no different. In the shadows of newly independent nations, where governments promised prosperity and sovereignty, a new class of power brokers emerged—men and women who learned to convert political privilege into private capital. Over time, they would form what can only be described as the Oil Block Mafia: a network of elites, officials, and foreign intermediaries who mastered the art of turning national resources into personal fortunes.

The story of this mafia is not one of crime in the conventional sense. It is the story of systemic capture—a silent colonization of the state from within. In this new order, oil blocks became the currency of loyalty, and political office the gateway to untold wealth. To understand its rise, one must look beyond the pump price of petrol or the fluctuations of global markets. The roots lie in governance itself—how access, accountability, and information are controlled.

By the early 2000s, the structure of this network had begun to harden. Across oil-producing states in Africa, control of licensing rounds, regulatory approvals, and production-sharing contracts was concentrated in the hands of a few. Ministries of petroleum and national oil companies—originally designed to manage public resources—became instruments of selective enrichment. Officials discovered that the true profit did not come from selling oil, but from selling access to oil.

A minister’s signature could change lives. A presidential decree could transfer billions from the public to the private realm. Shell companies sprang up overnight, often owned by the relatives or associates of political leaders. These entities would receive lucrative oil blocks, only to “flip” them to foreign investors at astonishing profit margins. The transactions were legal on paper, but their morality was indefensible. The resource meant to fund schools and hospitals instead built mansions and campaign war chests.

Transparency International’s assessments of corruption in sub-Saharan Africa tell part of this story. Across the region, corruption is not merely a byproduct of weak governance—it is the governing system itself. In oil economies, the convergence of wealth and power creates an unbreakable loop: political elites use oil wealth to maintain control, and control to secure more oil wealth. Elections become investments, cabinets become boards, and state institutions become subsidiaries in a sprawling, opaque enterprise.

But what makes this mafia uniquely resilient is its sophistication. Gone are the days of simple cash-for-contract bribery. The new generation of oil barons operates globally, moving wealth through offshore networks exposed by investigations such as the Pandora Papers. These leaks revealed an elaborate infrastructure of secrecy—trusts, shell companies, and anonymous holdings that stretch from Lagos to London, from Luanda to the British Virgin Islands. The money trails rarely end where they begin.

Each revelation confirms what citizens long suspected: the faces of power may change, but the system remains constant. Political transitions bring new rhetoric, but the oil licenses quietly pass from one insider to another. A change in administration simply reshuffles the beneficiaries. Those who once denounced corruption become its newest architects, cloaking their operations under layers of legality and national interest.

At the heart of this machinery is information control. In many African states, the press remains the first and last line of defense against secrecy. Yet journalists who venture too close to the oil economy face intimidation, censorship, or worse. Across the continent, press freedom is stifled precisely where the stakes are highest. Reporters uncovering oil-related scandals encounter lawsuits, surveillance, and orchestrated smear campaigns. In some cases, they are silenced permanently. Where transparency should prevail, fear becomes the language of governance.

This suppression is not incidental—it is strategic. The oil mafia thrives on opacity. Every exposed deal threatens the foundation of its power, and every question risks unraveling a billion-dollar network. In such an environment, even reformers within government tread carefully. Civil servants who demand accountability are transferred, demoted, or accused of disloyalty. Oversight institutions are deliberately underfunded, while anti-corruption agencies are politicized into weapons against opponents rather than tools of justice.

Consider the paradox of public reporting. In Nigeria, for instance, national transparency bodies release detailed reports on oil production, exports, and revenues. Yet these same documents often reveal what is not said: the missing contracts, the unaccounted funds, the gaps between declared and actual earnings. The figures are impressive, the charts modern—but behind them lies a deeper narrative of selective disclosure. The truth is told in fragments, never in full.

The international community, for its part, has often played a double role. While Western nations and global organizations preach transparency, many of their corporations are complicit in the very opacity they condemn. Multinationals enter joint ventures with politically connected firms, secure favorable tax terms, and exploit weak oversight mechanisms. For every African official who profits from corruption, there is often a foreign partner helping to structure it, document it, and legitimize it.

Over the decades, this alliance of local and global actors has evolved into a self-sustaining ecosystem. The Oil Block Mafia is not a cabal of villains gathered in secret rooms—it is a system built on mutual interest and maintained by institutional weakness. Its members do not see themselves as criminals; they see themselves as businessmen, patriots even, operating in the grey zones where politics, profit, and power overlap. Their success lies in how seamlessly they blend into the fabric of governance.

Yet the consequences of this collusion are devastating. The concentration of oil wealth among elites has eroded the social contract across the continent. Citizens no longer trust that their governments act in the public interest. National budgets are drafted in deficit while private jets crowd foreign runways. Youth unemployment soars even as oil revenues rise. And amid it all, governments insist that prosperity is “on the horizon”—a horizon that keeps moving further away.

Chatham House and other policy think tanks have long argued that sustainable resource governance requires not just transparency, but institutional independence and civic empowerment. It is not enough to publish data or sign onto global initiatives. Real reform demands dismantling the networks that link political office to private enrichment. Until that chain is broken, the oil sector will remain both the engine and the evidence of Africa’s deeper governance crisis.

Still, there are cracks in the armor. Civil society movements, data journalists, and reform-minded bureaucrats have begun to push back. They are tracing ownership structures, mapping revenue flows, and naming names. The task is immense, and the resistance fierce—but for the first time, the once-invincible oil mafia is facing sustained scrutiny. The myths of invulnerability are beginning to erode under the weight of digital transparency and international collaboration.

Yet reform is dangerous work. Every exposure threatens a powerful interest. Every disclosure risks retribution. Across the continent, courageous individuals—journalists, auditors, activists—are paying the price for asking questions that strike at the heart of entrenched power. Their resilience is the quiet rebellion that keeps democracy alive, even in nations where corruption has become culture.

The birth of the Oil Block Mafia was not a single event—it was a process, nurtured by greed, sustained by secrecy, and legitimized by institutions that forgot their purpose. What began as opportunism matured into an organized economy of extraction, invisible yet omnipresent. It is a system that feeds on silence, thrives on complexity, and hides behind the veneer of legality.

If Part 1 revealed where Africa’s oil wealth begins, Part 2 exposes who claims it first. The Oil Block Mafia is the middleman between the state and the people—a barrier made of contracts, shell companies, and influence. It was born not from chaos, but from design. Its birth certificate is written in every undisclosed contract, every offshore account, every intimidated journalist. And until the system that created it is dismantled, Africa’s oil story will remain not one of production, but of possession.

Part 3: The Godfathers of Crude

Meet the power brokers who turned oil into personal empires.

In every system of power, there are architects—individuals who transform corruption from a moral failure into a governing model. In Africa’s oil industry, they are known by many names: ministers, traders, tycoons, consultants. But together they form a more fitting title—the Godfathers of Crude. They are the faces behind the faceless networks, the men and women who learned to weaponize access, rewrite rules, and convert barrels into billions.

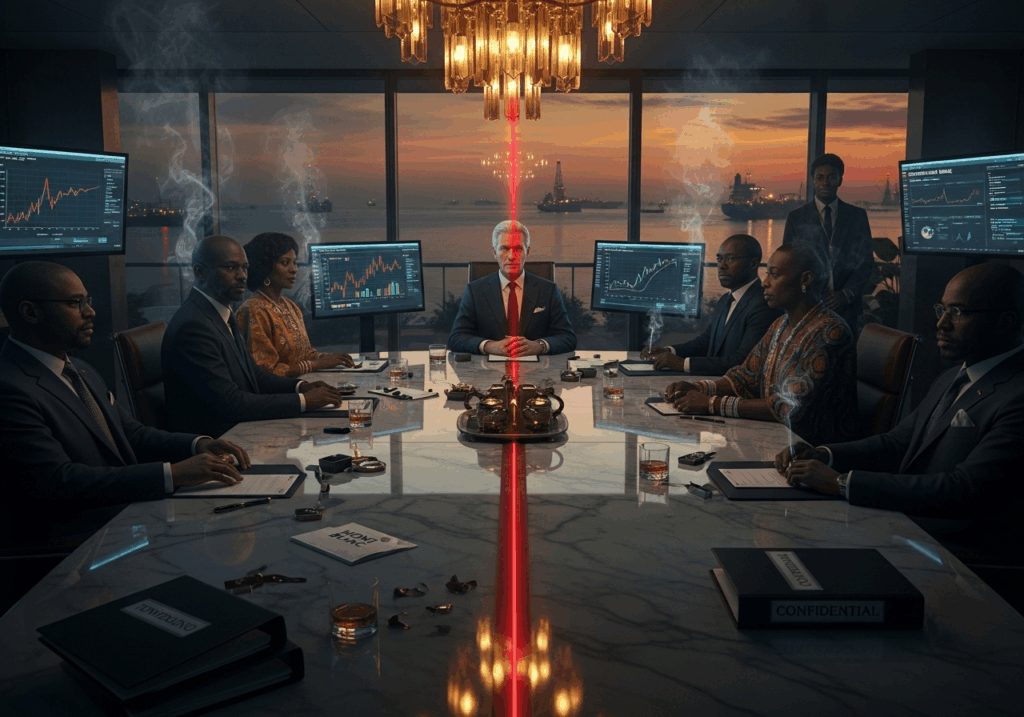

The Godfathers do not drill wells or refine petroleum. They operate in boardrooms, embassies, and offshore banks, orchestrating the flows of contracts and capital. Their genius lies not in technical skill but in political fluency—the ability to navigate, manipulate, and dominate a system where oil is the language of loyalty. Over the past three decades, they have redefined the meaning of public office and privatized the meaning of national wealth.

The rise of the Godfathers can be traced through a pattern of scandals and prosecutions that have rippled across the continent. Each case reveals a fragment of a larger story: a network so deeply entrenched that even when exposed, it regenerates.

In Nigeria, the recent seizure and repatriation of tens of millions of dollars linked to a former oil minister illustrates both the scale and sophistication of this corruption. The funds, scattered across multiple jurisdictions, were part of a fortune allegedly amassed through manipulation of oil block allocations and trading deals. The individuals involved were not petty thieves; they were policymakers—those entrusted with the nation’s most strategic resource. Their crimes were not hidden in secrecy but cloaked in official authority.

Across West and Central Africa, the pattern is eerily consistent. Multinational trading houses—names known on every stock exchange—have been implicated in bribery schemes stretching from Cameroon to Equatorial Guinea. Their executives negotiated “facilitation payments,” disguised as consultancy fees, to secure favorable oil trading rights. In one ongoing case, a prominent international trader faces charges of orchestrating multimillion-dollar bribes to public officials, ensuring his firm’s dominance over the region’s crude exports. The sums involved are staggering, but what’s more staggering is how routine such transactions have become.

For decades, the oil economy has created its own nobility—a transnational elite whose power transcends borders. The Godfathers of Crude are not confined to Africa; they are equally at home in London, Geneva, and Dubai. Some are former ministers who reinvented themselves as “energy consultants.” Others are foreign traders who mastered the art of influencing African bureaucracies. Many are connected through offshore structures exposed in investigations like the Pandora Papers—where private jets, mansions, and trust funds trace back to public wealth.

These revelations show that corruption is not an accident of weak institutions; it is the business model of the oil economy. It survives because it benefits too many powerful players—both local and global. In this ecosystem, African elites provide access, and foreign corporations provide legitimacy. The partnership is mutually profitable, deeply entrenched, and sustained by a shared understanding: secrecy is survival.

What distinguishes the Godfathers from ordinary corrupt officials is their endurance. They outlast regimes, transcend scandals, and adapt to reforms. They are the fixed stars in a rotating constellation of governments. Even when one administration falls, the networks remain intact—waiting patiently to attach themselves to the next. Each new reform effort becomes an opportunity to rebrand. The same individuals who once benefited from opaque licensing now champion “transparency initiatives,” using the language of accountability as a shield.

Behind the public posturing lies a more dangerous dynamic: the entanglement of political finance with oil money. Election campaigns across the continent are routinely underwritten by the proceeds of oil deals. The quid pro quo is simple—fund the race, win the block. Once in office, the cycle repeats. The Godfathers thus become indispensable; they are both the financiers and the beneficiaries of power. In this closed loop, governance ceases to be about service—it becomes a marketplace of influence.

The global dimension of this web cannot be overstated. Western and Asian corporations, desperate for access to crude reserves, often play the game willingly. In exchange for contracts, they offer political cover, legal advice, and, when necessary, plausible deniability. The result is a corruption complex that spans continents—African politicians on one end, foreign financiers on the other, with offshore havens in between. The oil itself is the least invisible part of the trade.

Yet, for all their power, the Godfathers operate on fragile ground. Each investigation, each leak, each indictment exposes a piece of their machinery. The recent wave of international probes into bribery and asset laundering has forced even the most powerful to reckon with accountability. In several African countries, former ministers, state oil executives, and foreign traders now face prosecution in foreign courts. These cases mark a rare reversal—where global financial transparency, long used to protect stolen wealth, begins to turn against its creators.

Still, justice moves slowly. Many of those charged continue to live lavishly, insulated by wealth and political connections. Their networks remain active, their influence intact. The prosecutions, though symbolically powerful, are often treated as isolated scandals rather than symptoms of a systemic disease. Without structural reform—stronger institutions, independent courts, and unflinching journalism—each victory will remain temporary.

The Natural Resource Governance Index paints a grim picture: despite decades of oil extraction, most African producers score poorly on transparency, accountability, and rule of law. The index reads like a ledger of lost potential. The Godfathers of Crude thrive in precisely these weak governance environments, where oversight bodies lack teeth and civic space is constricted. The fewer the questions, the greater the profit.

Behind their wealth lies an economy of silence. Public servants who refuse to sign dubious contracts are sidelined. Civil society organizations investigating oil corruption are defunded. Journalists face lawsuits for “defamation” merely for asking how billions disappeared. The result is a culture of fear and fatigue—a populace conditioned to believe that corruption is inevitable, and resistance futile.

Yet, beneath this despair, a quiet defiance persists. A new generation of African journalists, activists, and technocrats is refusing to inherit the cynicism of the past. Digital leaks, investigative collaborations, and data journalism are eroding the immunity once enjoyed by the oil elite. From Lagos to Nairobi, young professionals are demanding not just accountability but ownership—the right to know how their national wealth is managed and who truly benefits.

But exposing the Godfathers is not enough. The real challenge lies in dismantling the structures that produce them. Each scandal reveals not just individual greed but institutional failure—laws that allow anonymous ownership, regulators who answer to politicians, and political systems that depend on corruption for survival. Reform, therefore, must go beyond prosecution; it must rewire the relationship between resource wealth and political power.

The Godfathers of Crude are not relics of a bygone era—they are the architects of the present. Their empires were built not in defiance of the system, but through it. They embody a deeper truth about the oil age in Africa: that the real battles are not fought over who drills the wells, but over who controls the signatures that decide them.

They are the new aristocracy of postcolonial Africa—untouchable, transnational, and perpetually reinventing themselves. But like all empires built on excess and deceit, their dominion is not eternal. The tide is shifting. Each whistleblower, each court ruling, each public reckoning chips away at the illusion of invincibility.

History will not remember the Godfathers for their riches, but for the ruins they left behind—empty treasuries, polluted deltas, and a generation of citizens robbed not just of wealth, but of faith in governance itself. And when the wells of crude finally run dry, their legacy will remain written not in oil, but in the stain it left on the conscience of a continent.

Part 4: Deals in the Dark

Inside the boardrooms where billion-dollar deals are signed in silence.

Oil is not just a commodity; it is a currency of power. And nowhere is that power more invisible—and more corrupting—than in the dark corners where deals are made. The public sees pipelines, tankers, and exports. What they rarely see are the quiet negotiations behind closed doors—the boardroom bargains, offshore contracts, and handshake arrangements that determine who profits and who is left behind.

In Africa’s oil industry, the true wealth of nations is decided not in parliament or public hearings, but in private meetings between politicians, traders, and intermediaries. These are the “deals in the dark,” where billion-dollar resources are exchanged under the cover of national interest and legal ambiguity. They form the operating core of what has become the continent’s most enduring and elusive system of corruption.

At first glance, the architecture of these deals appears legitimate. There are contracts, legal frameworks, and bidding rounds that mimic international standards. Governments proudly announce new licensing processes, echoing the language of transparency and reform. Yet, beneath the official statements lies a deeper reality—a choreography of deceit, carefully designed to look lawful while concealing its true beneficiaries.

The anatomy of an oil deal in Africa follows a predictable script. A government agency opens a licensing round. A handful of companies—often preselected—submit bids. Then, through an opaque evaluation process, certain firms miraculously emerge victorious. Their success has little to do with merit or capacity; it is the product of influence, patronage, and payment. The contracts that follow are drafted in secrecy, shielded by “confidentiality clauses” that claim to protect commercial interests but, in truth, protect corruption.

Even when transparency frameworks mandate disclosure, governments often comply selectively. They publish summaries, not full contracts. They redact critical details—such as royalty rates, profit-sharing formulas, and ownership structures. The result is a system that appears open but is, in essence, a façade.

The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), which has long championed contract disclosure and anti-corruption measures, has made significant strides in establishing global norms. Yet, many African governments interpret compliance as performance. They release just enough information to appear transparent while keeping the true mechanics of power concealed. For every published contract, there are dozens more buried in the drawers of ministries, beyond the reach of auditors or citizens.

The power of secrecy extends beyond the state. International corporations—trading houses, law firms, and consultancies—play a crucial role in constructing these opaque arrangements. They design the offshore entities, structure the tax loopholes, and provide the legal cover that enables African elites to siphon wealth abroad. It is a collaborative enterprise: politicians offer access; corporations offer expertise; banks offer discretion.

Through this alliance, wealth flows out of Africa as easily as oil flows from its wells. The sums are staggering. Every year, tens of billions of dollars in profits vanish into tax havens—money that could fund infrastructure, healthcare, or education. According to global financial watchdogs, Africa loses more through illicit financial flows and tax evasion than it gains in foreign aid. The oil industry sits at the heart of this equation, its transactions hidden in complex layers of corporate secrecy.

Behind the euphemism of “offshore finance” lies a blunt truth: the world’s financial system is built to enable theft at scale. In the world of oil, this theft is legalized through shell companies, nominee directors, and anonymous trusts. The revelations of the Pandora Papers exposed how deeply entrenched these mechanisms have become. African politicians, business magnates, and foreign intermediaries appeared across the leaks—each connected to secret companies registered in the British Virgin Islands, Mauritius, or Dubai. These firms serve a single purpose: to hide the movement of money from public scrutiny.

The real tragedy is that this system persists in plain sight. Everyone—from regulators to diplomats—knows how the game is played. Yet, it continues because the architecture of global finance rewards opacity. Banks profit from secret accounts; law firms profit from structuring them; governments profit from the illusion of compliance. In the end, the cost is borne by citizens—those who see oil prices rise but never feel the wealth it should create.

In Nigeria, Africa’s largest oil producer, the pattern is both familiar and refined. Investigations into state oil operations reveal a labyrinth of contracts awarded to shell companies with unclear ownership, some linked to serving or former officials. Despite reform efforts and public audits, billions in potential revenue vanish each year through underreported exports, inflated costs, and untraceable payments. Reformers speak of “new transparency standards,” but behind the language lies an old problem: too many people benefit from the darkness.

Chatham House analysts have long observed that anti-corruption strategies in resource-rich states fail not because of a lack of laws, but because of a lack of political will. The decision to disclose—or conceal—contracts is itself a political act. It determines who controls information, and by extension, who controls power. When governments choose secrecy over openness, they are not protecting the state; they are protecting the network of individuals who feed off it.

The Tax Justice Network, in its latest assessment, describes this ecosystem as a “shadow economy of privilege.” It is an economy that transcends geography and ideology. Whether in democratic Ghana or autocratic Equatorial Guinea, the rules of the oil game remain the same: concealment is profit. The opacity is not merely tolerated; it is institutionalized. Ministries of energy, national oil companies, and finance departments operate as silos of secrecy, each guarding data as if it were a state secret.

The implications of these hidden deals go beyond corruption—they distort entire economies. When oil revenues are misreported or diverted, national budgets collapse under debt, exchange rates spiral, and citizens pay the ultimate price through inflation and austerity. The oil that should empower becomes a trap—a resource curse that feeds inequality and erodes faith in governance. Transparency, in this sense, is not a moral luxury; it is an economic necessity.

And yet, amid this landscape of concealment, a quiet revolution is stirring. The global movement for contract transparency is gaining traction. New EITI provisions require governments to publish full-text contracts within six months of signing. Civil society coalitions across Africa are using digital tools to track compliance and expose omissions. Investigative journalists, armed with data leaks and satellite imagery, are piecing together the hidden map of oil wealth.

Each revelation chips away at the myth of secrecy as power. Each published contract, each traced payment, weakens the fortress of privilege that has long defined the oil sector. The challenge now is to sustain momentum—to move from symbolic disclosures to systemic accountability.

Because every deal made in the dark leaves a shadow. And shadows, once illuminated, reveal not just corruption, but complicity. They reveal the uncomfortable truth that Africa’s oil problem is not a failure of capacity, but a failure of will—a deliberate choice to keep the public blind while a few grow rich.

The future of Africa’s oil wealth will not be decided in another round of reforms or summits, but in the decision to confront this darkness. To insist that contracts belong not to governments or corporations, but to the citizens whose resources they govern. The day that light pierces those boardrooms, and those hidden deals are brought fully into the open, will be the day Africa’s oil finally begins to serve its people—and not its godfathers.

Read also: The New Macroeconomics: Africa’s Global Blueprint

Part 5: When Politics Became Petroleum

Oil as a weapon—funding elections, silencing critics, and buying loyalty.

Power in Africa has long been spoken of in metaphors—tribal alliances, ethnic loyalties, patronage networks—but in the modern era, it runs on something far more tangible: oil. Crude has become the lubricant of political survival, the fuel of elections, and the silent architect of governance itself. In the corridors of African power, oil is not just a resource; it is a regime.

To understand how politics became petroleum, one must first understand the alchemy of power in resource-rich states. Oil revenues, once heralded as the key to development, have instead become a parallel political currency—unaccounted for, unbudgeted, and unrestrained. The vast sums generated by the sale of crude flow not into public infrastructure but into political machinery, feeding the same cycle of corruption that has hollowed out governance across the continent.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the periodic ritual of elections. In many oil-producing nations, campaign seasons coincide with spikes in unrecorded expenditures from state-owned enterprises. Official budgets remain flat, but money floods the streets—new vehicles for political loyalists, handouts for voters, construction projects that begin and end in a single week. It is no coincidence. In countries where oil exports are the dominant source of revenue, the line between public funds and political finance is virtually nonexistent.

The system works like a well-drilled rig. Government officials divert oil revenues—sometimes through “special accounts,” sometimes through outright embezzlement—to fund electoral dominance. Contracts are awarded to companies owned by political allies, who in turn funnel kickbacks into campaign coffers. Subsidy programs and fuel allocations become tools of political patronage, rewarding those who support the ruling elite and punishing those who dare to challenge it. Oil money becomes the invisible ink with which election results are written long before a single ballot is cast.

The consequences are profound. Democracy, starved of fairness, becomes an illusion maintained by cash flow. Political competition transforms into a contest of resource control, not of ideas or governance. Candidates no longer need popular legitimacy—only access to the state’s oil-fed treasury. In such a system, the winner’s first act is to consolidate control over oil revenues, ensuring that power never leaves his hands again. It is governance as extraction, politics as refinery.

This dynamic is not hidden—it is an open secret acknowledged in every corruption perception index, every fiscal report, every investigative exposé. Transparency International’s findings over the past decade consistently show that Africa’s most resource-endowed nations rank among its most corrupt. Wealth has not bred accountability; it has entrenched impunity. The richer the state in oil, the poorer it becomes in trust.

In Nigeria, Africa’s largest crude exporter, this paradox is visible in its most recent oil and gas audits. Despite producing billions of dollars annually in petroleum income, the country still grapples with missing funds, unremitted revenues, and unexplained payments. Billions are lost between production and remittance—disappearing through “technical adjustments” and opaque subsidy programs that have long doubled as political slush funds. Every administration vows reform, yet every reform finds its limits at the intersection of transparency and political self-preservation.

The International Monetary Fund’s research on fiscal governance in sub-Saharan Africa captures the macroeconomic consequences of this political economy. When oil money becomes a political tool, fiscal discipline collapses. Governments overspend in election years, neglect savings mechanisms, and plunge into debt when oil prices fall. Public expenditure becomes reactive, not strategic—driven by political cycles rather than national priorities. Economies oscillate between windfall excess and austerity famine, while infrastructure crumbles and poverty persists.

The problem is not simply mismanagement—it is design. Oil-dependent governments treat fiscal policy as political leverage. State-owned oil companies are often insulated from public oversight, operating as cash machines for the ruling class. Their accounts are opaque, their transactions untraceable. Budgets are drafted with optimistic oil price forecasts to justify higher spending, ensuring a steady flow of funds for patronage and loyalty-building. When prices crash, the debt burden is transferred to citizens through taxation and subsidy removal.

This cycle turns every fiscal crisis into a political one. Citizens, angry over fuel shortages or inflation, protest against governments that have long sold them promises of abundance. Yet, behind each crisis lies the same equation: a leadership addicted to oil rents and a political culture built on their distribution. The more governments depend on oil to maintain control, the less incentive they have to diversify their economies or democratize their institutions. Petroleum thus becomes not only a resource curse but a governance curse—a mechanism that turns power itself into a commodity.

This commodification of governance explains why corruption cases linked to oil often reach the highest offices. When U.S. authorities recently returned millions in seized assets connected to a former African oil minister, it was not merely an indictment of individual greed—it was a snapshot of an entire system. Those funds represented the invisible transactions through which oil wealth circulates in the political bloodstream: from state coffers to private accounts, from private accounts to campaign funds, from campaign funds back to state coffers through inflated contracts. The circle closes perfectly, leaving nothing for the public but the residue of promises.

Meanwhile, international institutions, though increasingly vocal, face their own contradictions. They issue stern warnings about fiscal transparency and compliance, but their loans and technical support often flow through the very governments they critique. Reports call for “risk management frameworks” and “compliance modernization,” yet these frameworks are only as strong as the political will to implement them. And that will evaporates the moment it threatens the system that sustains those in power.

In this intricate web of oil and politics, even anti-corruption measures can be weaponized. Whistleblowers are targeted under the guise of “national security.” Anti-graft agencies pursue opposition figures more aggressively than ruling party officials. Compliance offices are created not to monitor corruption, but to manage its exposure. Reform becomes a performance, not a policy. The same officials who sign anti-corruption pledges sign secret contracts the next day.

And the costs are not abstract. Each dollar diverted from oil revenues is a dollar denied to hospitals, schools, and infrastructure. The IMF’s fiscal analyses reveal that oil-rich African countries often spend more on subsidies for political stability than on public welfare. In nations where pipelines cross slums and power outages last for days, citizens live in the paradox of abundance—the sight of wealth they can neither touch nor taste.

When politics becomes petroleum, the moral boundaries of governance dissolve. Public office transforms into a private enterprise, elections into auctions, and leadership into logistics. The people, once seen as sovereign, become shareholders without dividends in an enterprise run for profit by the few.

Yet even within this bleak landscape, the prospect of accountability glimmers faintly. Civil society coalitions are using audit data and fiscal reports to expose hidden flows. Journalists are tracing campaign finances back to oil contracts. Economists are demanding fiscal rules that separate resource revenue from political expenditure. The fight is slow, often perilous, but persistent.

Africa’s political salvation may ultimately depend on its ability to decouple power from petroleum—to ensure that oil funds the state, not the state’s survival. Transparency is not merely about publishing data; it is about dismantling the financial umbilical cord that ties democracy to crude.

For as long as oil money remains the oxygen of politics, reform will suffocate at birth. The wells will keep producing, but what they feed will not be development—it will be dominance. And until that cycle is broken, every drop of oil drawn from African soil will bear not just the scent of wealth, but the stain of power.

Part 6: The Foreign Hand

Global powers and corporations in Africa’s crude game.

Every empire needs enablers. In Africa’s oil story, they wear suits, not uniforms. They sit in boardrooms in London, Paris, Houston, and Beijing—far from the noise of refineries or the fumes of the Niger Delta. Yet their signatures, investments, and trade flows shape the destinies of entire nations. This is the foreign hand: the invisible architecture of global interests that props up Africa’s most enduring and profitable dysfunction—its oil corruption.

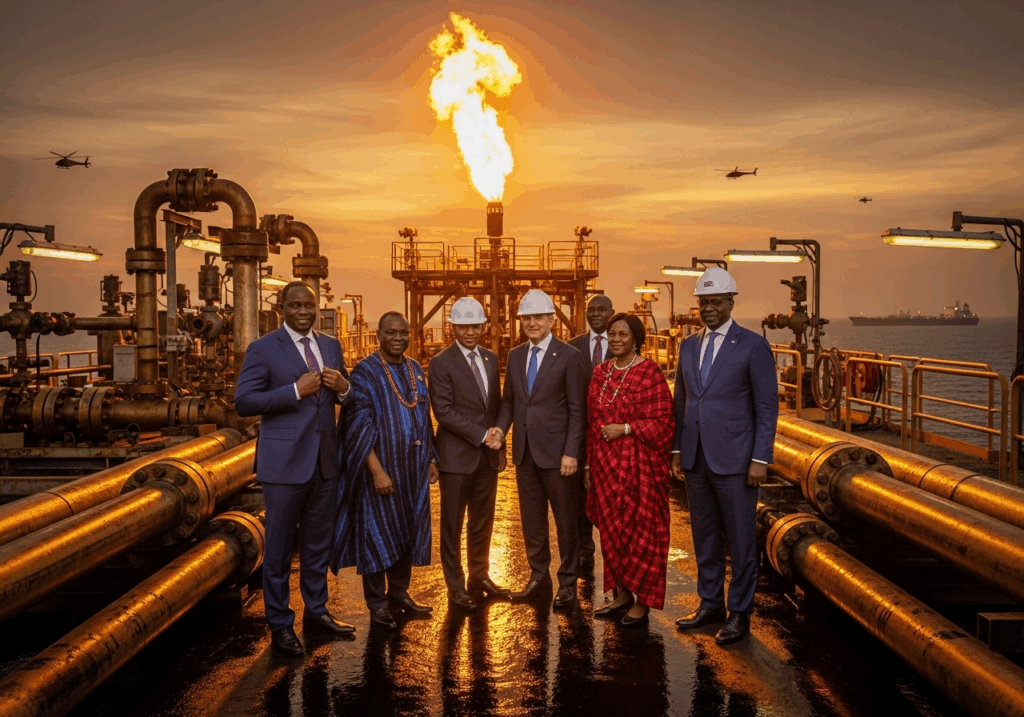

For decades, Africa’s oil has been both a lifeline and a leash. Its vast reserves have drawn foreign capital and influence, but that same interest has entrenched dependence and secrecy. The continent’s oil-producing nations—Nigeria, Angola, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Libya—operate within a global system designed not for empowerment, but extraction. Foreign corporations, investors, and governments present themselves as partners in development. In truth, they are patrons in a global network that thrives on asymmetry.

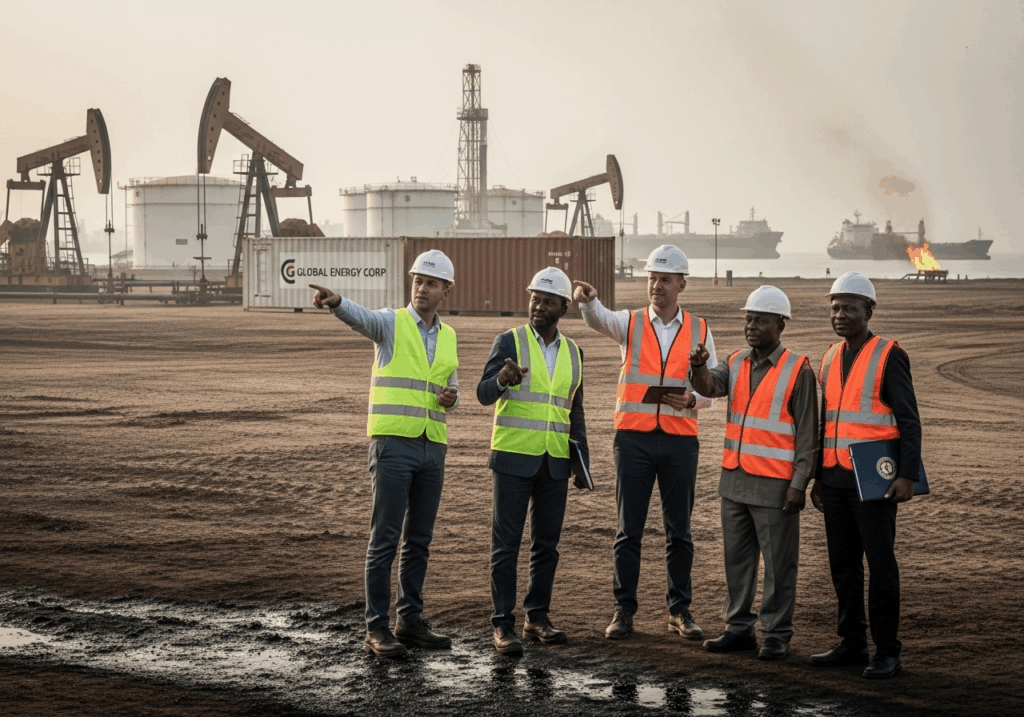

To understand the foreign hand, one must begin with energy demand. Global consumption drives Africa’s production. Every barrel extracted from the continent feeds a chain of refineries, tankers, and trading desks stretching across the Atlantic and beyond. According to the International Energy Agency, Africa now produces roughly 8% of the world’s oil supply, yet consumes barely a fraction of it. The wealth extracted flows outward—to shareholders, lenders, and foreign treasuries—leaving behind only the residue of environmental damage and political decay.

The economic imbalance is not accidental. Oil has always been the instrument through which foreign powers project influence across the continent. During the Cold War, it was a strategic prize; in the postcolonial era, it became a commercial one. Western and Asian corporations alike embedded themselves in Africa’s oil industries, offering technology, loans, and “expertise” in exchange for access. The deals, shrouded in technical jargon and investment clauses, often locked African states into decades of dependence—reliant on external capital, foreign contractors, and imported governance standards.

In this relationship, control is exercised not through force, but through finance. Multinational companies dominate upstream exploration and trading, while global banks structure the loans that fund national oil projects. Each dollar of investment carries conditions—tax exemptions, arbitration clauses, confidentiality guarantees—that favor the investor and constrain the host. The result is a sovereignty that exists in name but not in practice. African governments sign contracts that legally cede control of their own resources to entities domiciled thousands of miles away.

The paradox deepens when one considers the global oil economy itself. According to the International Energy Agency’s most recent analysis, the world’s oil and gas companies now spend half a trillion dollars each year merely to sustain production levels. It is a staggering figure that reveals a deeper truth: the system is addicted to its own inertia. The push for “energy security” in the global North keeps Africa locked in an extractive role—its oil essential to the world’s consumption, yet inconsequential to its prosperity.

This dependency extends beyond legitimate trade. In the Niger Delta, the world’s appetite for crude fuels a shadow industry of theft and smuggling that costs billions annually. Despite military crackdowns and surveillance operations, oil bunkering persists—an elaborate network of insiders, militants, and foreign intermediaries working together to siphon crude into the black market. Tankers with falsified manifests disappear into international waters; refined products reappear in neighboring states. The profits move invisibly through the same global financial arteries that service legitimate trade. Demand creates corruption, and corruption sustains demand.

This convergence of legal and illegal economies is the essence of the foreign hand. The same systems that facilitate billion-dollar corporate transactions also launder stolen oil. The same banks that handle state revenue accounts host private accounts for politically exposed persons. The same international courts that enforce investment protections for foreign companies are silent on the billions lost to illicit financial flows. The line between governance and gangsterism dissolves when profit is the only principle.

Foreign corporations, for their part, justify their presence with the rhetoric of development. They point to jobs, infrastructure, and social responsibility projects. But these gestures are drops in an ocean of asymmetry. The true measure of impact lies not in the schools they build but in the contracts they sign—contracts that grant tax holidays for decades, lock in profit-sharing terms heavily skewed in their favor, and shield commercial data from public view. The “partnerships” they promote are rarely between equals. One side brings resources and sovereignty; the other brings capital and control.

Chatham House has long argued that the future of African resource governance depends on breaking this dependency cycle. True reform, it notes, requires more than national transparency—it requires international accountability. Yet global governance structures have been slow to evolve. The financial secrecy that sustains corruption in Africa is entrenched in the very jurisdictions that preach reform. Western capitals, not African ones, are where stolen oil wealth is hidden, invested, and legitimized.

It is easy to blame African leaders for corruption; harder to confront the global machinery that enables it. Oil traders who bribe ministers operate under the protection of multinational corporations. Lobbyists in Washington and London advocate for regimes that guarantee “stability”—a euphemism for predictable corruption. Development loans flow to governments that promise reform but deliver opacity. And when scandals erupt, the world’s outrage is conveniently selective.

Even the emerging global energy transition exposes this hypocrisy. As developed nations move toward renewables, Africa is being urged to continue producing oil—for export, not for domestic energy security. The continent is asked to power the world’s cars and factories while its own citizens sit in darkness. The International Energy Agency predicts that Africa’s population will nearly double by 2050, driving massive demand for energy access. Yet most of that access remains theoretical, because the infrastructure and revenue to deliver it are siphoned abroad.

The foreign hand, therefore, is not a singular force but a structure—a vast and self-perpetuating system that treats African oil as a means to sustain global consumption while outsourcing its moral cost. It is visible in the offshore companies that hold African contracts, the think tanks that sanitize corporate interests as “development partnerships,” and the diplomats who call corruption “market friction.” It is a form of neo-colonialism refined to perfection—no longer through occupation, but through ownership.

Yet even this architecture is showing cracks. International scrutiny is rising. Data leaks, global tax justice campaigns, and investigative collaborations are exposing how deeply Western and Asian corporations are implicated in African oil corruption. The façade of moral distance is collapsing. The same governments that once turned a blind eye to illicit trade now face domestic pressure to regulate their corporations abroad. Civil society alliances are demanding global standards for transparency in energy investment, corporate taxation, and contract disclosure.

Still, reform will remain hollow unless it is mutual. Transparency cannot be imposed on Africa while secrecy is preserved in the West. The pipelines of accountability must run both ways—from Lagos to London, from Luanda to Geneva. Only then can Africa’s oil wealth cease to be a global feeding trough and become the foundation of domestic prosperity.

For decades, Africa’s oil wells have been the beating heart of a global machine powered by inequality. The foreign hand built that machine—and still controls its levers. But the moment that hand loses its grip, the continent’s resource story could be rewritten: from extraction to empowerment, from dependency to dignity. Until then, the oil will keep flowing, and so will the silence.

Part 7: Paper Empires and Shell Companies

Tracing Africa’s stolen oil money through the offshore maze.

Every empire has its castles. The oil empire’s are made not of stone or steel, but of paper. They exist in the quiet abstractions of corporate registries—in the thin air between a lawyer’s signature and a banker’s code. They have no workers, no factories, no offices. Yet these paper empires control billions in assets, own fleets of tankers, and decide the fate of nations. They are the shell companies and financial havens through which Africa’s oil wealth vanishes into the shadows.

Behind every major corruption scandal in the oil sector lies one common denominator: opacity. Not the kind born of ignorance, but the kind engineered by design. The world’s financial system was built to move capital efficiently—but also to conceal it expertly. What began as a mechanism for global trade evolved into a sanctuary for tax evasion, illicit enrichment, and state looting. In this system, secrecy is not a flaw; it is a feature.

Africa’s oil corruption could not survive without it. The theft of billions in oil revenue each year is only possible because the stolen money has somewhere to go—a destination where questions are not asked and ownership can dissolve like smoke. For decades, that destination has been the global offshore network: a labyrinth of shell companies, trusts, and nominee accounts stretching from London to Dubai, from Mauritius to the British Virgin Islands.

These shell companies are the oxygen of the oil mafia. They are created with a few signatures, registered under the names of lawyers or accountants, and used to hold lucrative contracts, assets, or bank accounts. Their ownership trails end in a maze of legal proxies. Their purpose is not to operate businesses but to obscure who really owns them. Through them, public wealth becomes private, and private accountability disappears.

The Financial Secrecy Index, published by the Tax Justice Network, paints a sobering picture of how deeply entrenched this problem is. The world’s most powerful economies—those that preach transparency—rank among the largest enablers of secrecy. Jurisdictions like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland dominate the index, providing the legal infrastructure through which African elites conceal their oil proceeds. Financial secrecy, as the report notes, is not just an economic distortion; it is a democratic threat. When wealth escapes accountability, so does power.

In Africa, the effect is devastating. Oil revenues that should flow into national treasuries are rerouted into shell firms abroad. These firms—often owned by politically exposed persons—receive inflated payments for “consultancy,” “logistics,” or “brokerage” services. The invoices are fake, the payments real, and the trail cold. Once the funds reach offshore accounts, they are laundered through property purchases, luxury assets, or investment portfolios in Western capitals. By the time investigators notice, the money has changed form a dozen times.

The Pandora Papers offered a rare glimpse behind this curtain. The leaks revealed a web of African politicians, businessmen, and intermediaries using offshore entities to hide wealth derived from public office. Oil contracts awarded to shell companies with no technical capacity turned out to be fronts for ministers, military officials, and their associates. Their justification was always the same: “commercial confidentiality.” In truth, confidentiality meant concealment.

This concealment is not confined to Africa’s borders. The offshore system is a global symbiosis between those who steal and those who protect the stolen. For every African politician hiding money, there is a Western law firm drafting incorporation documents, a foreign bank accepting deposits, and a consultant providing “asset management.” The architecture of secrecy is built in the North, but exploited in the South.

What makes this system particularly insidious is its legitimacy. Shell companies are legal. So are trusts, nominee directors, and cross-border investments. The problem is not legality—it is intent. These instruments are neutral until they are weaponized for corruption. And when they are, they provide perfect cover: complex, technical, and seemingly compliant. This veneer of legality allows billions to move unnoticed, unchallenged, and untaxed.

Efforts to expose beneficial ownership—the real people behind corporate structures—have gained traction in recent years. Initiatives such as the Opening Extractives partnership, a collaboration between the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative and Open Ownership, have pushed for public disclosure of company ownership in the extractive sector. Some African countries have begun publishing registers, naming individuals behind once-anonymous companies. It is a quiet revolution, but one that threatens the very foundation of the paper empire.

Yet progress remains fragile. Even where ownership disclosure is required by law, enforcement is weak. Registers are incomplete, inconsistent, or riddled with loopholes. Companies exploit technicalities to conceal true beneficiaries—using family members, offshore subsidiaries, or “trustees” to mask control. In some cases, national registries are not even digitized, making verification nearly impossible. The opacity is so entrenched that reformers are often forced to rely on leaks and whistleblowers rather than institutional transparency.

The stakes are enormous. According to financial transparency researchers, Africa loses tens of billions of dollars annually through tax evasion, illicit financial flows, and trade misinvoicing—losses that dwarf foreign aid and development finance combined. Oil, with its high value and low traceability, remains the chief vehicle for these flows. Each untraced dollar represents a road not built, a hospital not equipped, a future deferred.

The persistence of this secrecy also has political consequences. Hidden wealth fuels political continuity. The same elites who control oil revenues use their offshore assets to finance elections, buy loyalty, and insulate themselves from domestic accountability. The ability to move money abroad at will transforms power into permanence. Corruption thus becomes not only profitable but sustainable.

The irony is that global financial transparency is technologically possible but politically inconvenient. The world has the data, the tools, and the standards to trace ownership in real time. What it lacks is the will. The same jurisdictions that demand reform from developing nations resist it at home, citing privacy, competition, or national interest. They condemn corruption abroad while profiting from the secrecy that sustains it.

This hypocrisy is not lost on African reformers. Increasingly, civil society organizations are calling for reciprocity in transparency—demanding that Western governments open their own corporate and trust registries to scrutiny. The argument is simple: corruption is a two-way street. If Africa is to expose its thieves, the world must expose its enablers.

Still, the tide is shifting. The pressure for beneficial ownership disclosure is mounting globally. Banks are being forced to tighten compliance; tax authorities are sharing data across borders; and journalists continue to pry open the doors of secrecy. Each revelation—from Panama to Pandora—chips away at the myth of anonymity that once shielded the powerful. The paper empire, once invisible, is slowly becoming transparent.

But until full transparency is achieved, these ghost companies will continue to haunt the continent’s prosperity. They are the vaults of stolen futures, the invisible infrastructure of inequality. Behind every shell company lies a real community deprived of development, a real worker unpaid, a real citizen betrayed.

Africa’s oil story is not only about extraction—it is about evasion. The wells may be local, but the theft is global. The fight for transparency, therefore, cannot stop at the border; it must follow the money to its final destination. Because as long as the world’s financial capitals remain safe havens for stolen wealth, the continent’s paper empires will stand—silent, legal, and lethal to the dream of equitable progress.

Part 8: The Cost of Silence

How whistleblowers disappear and journalists are silenced.

Every corrupt system has its enforcers—but not all carry guns. Some wield laws, others wield fear. In the theater of Africa’s oil corruption, silence is not the absence of sound—it is a strategy of control. It is manufactured, enforced, and, when necessary, bought. For those who dare to pierce that silence—journalists, activists, whistleblowers—the cost is often their freedom, their livelihood, or their lives.

The cost of silence is measured not only in the billions lost to corruption but in the voices lost to intimidation. Across Africa’s resource-rich states, truth-telling has become a dangerous profession. To expose how oil money is stolen is to stand against a machinery that fuses wealth with power and power with impunity. The whistleblower who leaks a document, the reporter who names a minister, the activist who organizes a protest—each becomes a target in a system that treats scrutiny as treason.

The Committee to Protect Journalists’ recent assessment of press freedom paints a grim portrait of this reality. Across the continent, journalists covering corruption, environmental degradation, or state-linked oil scandals face harassment, arbitrary detention, and prosecution under sweeping security laws. The message is clear: there are truths the powerful will not allow to be told.

In Nigeria, for example, the arrest of a journalist who investigated oil-sector kickbacks drew national and international condemnation. His case was not unique—it was emblematic. The state’s response to scrutiny is rarely to refute, but to punish. Journalists are accused of defamation, “cyberstalking,” or spreading “false information.” In some cases, their newsrooms are raided, their equipment seized, their families threatened. The goal is to make the act of questioning so costly that silence becomes the safer option.

This culture of repression extends far beyond the press. Activists documenting oil pollution, land grabs, and revenue diversion are routinely branded as “foreign agents” or “enemies of development.” Community leaders who resist the expropriation of their lands for oil projects are intimidated by security forces. Whistleblowers within state oil companies face dismissal, prosecution, or worse. The message radiates across societies: loyalty is rewarded, dissent punished.

The statistics tell a chilling story. Global Witness has documented the killings and disappearances of more than a hundred environmental and land defenders across Africa and Latin America in a single year. Many of these deaths occur in areas where oil and gas interests overlap with fragile governance and high-value land. These are not random acts of violence—they are systematic acts of erasure. Each murdered activist is a warning to others: the pipeline must flow, the wells must pump, the profits must continue.

In oil-dependent states, repression and extraction are two sides of the same coin. To protect the flow of revenue, regimes must also control the flow of information. Security forces, often trained and equipped under the banner of “protecting critical infrastructure,” are deployed not just against oil thieves, but against communities protesting pollution or demanding compensation. The militarization of the oil economy transforms citizens into threats, and transparency into sedition.

Yet the silence is not always enforced by the state alone. Corporations, too, play their part. Multinationals operating in high-risk environments often contract private security firms that act as de facto paramilitary units. Their mandate is to secure “operational stability”—a euphemism for suppressing unrest. Local journalists who investigate corporate malfeasance are blacklisted from press briefings; activists are excluded from “stakeholder consultations.” Corruption thrives in this choreography of intimidation, where every actor has a role and every risk is managed—except the truth.

The result is a profound moral inversion: those who steal from the public are protected by law, while those who expose them are criminalized. Governments pass whistleblower protection acts, yet whistleblowers continue to vanish. International donors fund “media development,” yet newsrooms remain under surveillance. In this environment, silence becomes not just a survival strategy—it becomes policy.

The human cost is immense. Behind every censored report lies a journalist working under threat, every shuttered NGO an activist forced into exile. Families are left without answers, colleagues without closure. Entire communities, especially in oil-producing regions, are deprived of representation because speaking out has become synonymous with danger.

The Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index for Africa illustrates how this repression corrodes democracy. In countries where oil dominates national income, media freedom consistently ranks among the lowest. The correlation is no coincidence. Where oil rents replace taxation, governments no longer need to be accountable to their citizens—they only need to control them. Information becomes a threat to the stability of the rentier state, and thus, a target.

This pattern creates what analysts describe as a “fear economy.” The price of silence is high, but the price of speech is higher. Citizens learn to censor themselves, journalists to temper their investigations, editors to avoid the oil beat altogether. The result is an epistemic blackout: corruption becomes invisible, normalized, and self-reinforcing. The oil keeps flowing, the money keeps disappearing, and the public remains none the wiser.

But silence, no matter how carefully constructed, is never absolute. Across the continent, a new generation of journalists and activists is finding creative ways to break it. Digital media has become their refuge—an arena harder to police, easier to mobilize. Investigative platforms collaborate across borders, pooling data and publishing from safe jurisdictions. Social media amplifies suppressed stories, turning censorship into a catalyst for innovation.

Still, these gains are precarious. Governments are learning to extend their control online, deploying cybercrime laws and digital surveillance tools to stifle dissent in virtual spaces. Some countries have even introduced licensing regimes for online media, effectively extending censorship from the newsroom to the smartphone. The battlefield has shifted, but the struggle remains the same: who controls the story of power?

The most tragic irony is that those silenced are often the very people trying to protect national interests. Whistleblowers exposing theft in the oil sector are not traitors—they are patriots. Journalists documenting pollution are not saboteurs—they are witnesses. Environmental defenders risking their lives in oilfields are not radicals—they are custodians of the public trust. Yet in the upside-down logic of petro-politics, their courage is treated as criminality.

This inversion speaks to the heart of Africa’s governance crisis. Corruption does not merely survive by hiding the truth—it survives by punishing those who seek it. And in that punishment lies the ultimate deterrent: fear. The silence that blankets Africa’s oil states is not the silence of apathy; it is the silence of intimidation, cultivated by power and fertilized by impunity.

Still, history suggests that silence is never permanent. The truth, however suppressed, leaks—like oil itself—from the smallest cracks. It seeps through documents, through leaks, through the voices that refuse to be buried. The cost of silence is high, but the cost of ignorance is higher. Each journalist arrested, each activist lost, reminds the world of what is truly at stake—not just transparency, but the right of citizens to know how their wealth is spent, how their environment is governed, and how their future is traded.

Africa’s oil story has always been told through power. But it is the silenced voices—the reporters, the whistleblowers, the defenders—who remind us that power, no matter how absolute, is never immune to truth. For every silence imposed, another voice will rise to fill it. The wells of truth may be buried deep, but they are never dry.

Part 9: The People’s Wealth, The People’s Poverty

Why oil-rich nations remain poor and unstable.

Africa is a continent of riches that breeds poverty. Its soil is abundant, its waters deep, its subsoil bursting with minerals and crude oil that the world covets. Yet for millions of Africans, this wealth has translated not into prosperity, but into penury. Roads crumble, hospitals decay, schools fail, and electricity flickers—while the same resources that could build nations instead bankroll opulence for the few. This is the central paradox of Africa’s oil story: the richer the state in natural resources, the poorer its citizens tend to be.

Nowhere is this more glaring than in the oil economies that line the Gulf of Guinea and the Sahel. These nations generate billions of dollars from petroleum exports, yet their people live under the shadow of scarcity. The contradiction is not accidental—it is systemic. Oil has not only distorted Africa’s economies; it has corrupted the very logic of governance. The promise of prosperity that accompanied the discovery of crude has been swallowed by a machinery of mismanagement, secrecy, and political greed.

The Resource Governance Index, which assesses transparency and accountability in extractive sectors, captures this failure with numerical precision. Most sub-Saharan African producers score poorly on revenue management, contract disclosure, and public accountability. The numbers reveal what citizens have long known: the resource sector is governed not for the public good but for private gain. The oil wells enrich elites while entire regions remain untouched by development.

In theory, oil revenue should be the engine of transformation—funding schools, power grids, hospitals, and industrial diversification. In practice, it functions as political lubricant. It sustains patronage networks, funds elections, and props up bureaucracies that exist to preserve themselves. The institutions meant to manage oil wealth—the ministries, national oil companies, and sovereign wealth funds—too often become conduits for corruption rather than guardians of growth.

The results are devastatingly visible. In Nigeria, Africa’s largest producer, billions in oil income pass through public accounts each year, yet nearly half the population lives below the poverty line. Across Angola, Gabon, and Equatorial Guinea, high per-capita revenues coexist with staggering inequality. The pipelines that carry crude to export terminals run through communities without potable water. Villages near oilfields glow with gas flares at night while their children study by candlelight. The oil that illuminates foreign cities leaves darkness at home.

The Africa Energy Outlook notes that nearly 600 million Africans still lack access to electricity, including in countries that export massive volumes of oil and gas. This contradiction underscores how energy wealth has been exported, not shared. The infrastructure built to serve extraction—pipelines, export terminals, refineries—rarely benefits the people living alongside them. Instead, these communities bear the environmental cost: polluted rivers, poisoned soil, and the slow violence of economic exclusion.

This disconnect between wealth and wellbeing is rooted in governance failure. Transparency International’s corruption index has long shown that the most resource-dependent nations rank among the most corrupt. Where oil rents dominate public finance, accountability erodes. Governments rely not on taxation but on the steady inflow of resource rents, severing the fiscal bond between rulers and the ruled. Citizens who do not pay taxes are easier to silence; governments that do not depend on taxpayers are easier to corrupt. In such states, politics becomes a contest over control of oil, not a mandate to serve the people.

The social costs are profound. Oil has created not shared prosperity but stratified societies—tiny islands of wealth amid oceans of want. In capital cities, skyscrapers and luxury cars testify to the reach of oil money. In the rural hinterlands, the same wealth manifests as absence—of roads, schools, clean water, and opportunity. Development budgets leak like punctured pipelines. Funds earmarked for public welfare evaporate through inflated contracts, ghost projects, and “special accounts.”

Organizations like Connected Development (CODE) and BudgIT have documented this hemorrhage of public funds in meticulous detail. Their reports track how allocations for community development projects often exist only on paper. Roads that should connect villages remain sketches in budget documents. Health centers built in name only stand as empty shells, their funds siphoned before a single brick is laid. Transparency portals and fiscal reports provide the illusion of openness, but beneath the data lies a chasm of deceit.

This “paper development” mirrors the “paper empires” of offshore finance: both are constructs of concealment. Budgets are announced, contracts signed, revenues reported—but the impact on citizens remains invisible. The same culture of opacity that hides billions abroad also hides poverty at home. The poor become statistics, their suffering measured in percentages rather than lives.

What makes this tragedy uniquely cruel is its predictability. Economists have long warned of the “resource curse”—the paradox whereby resource wealth breeds economic stagnation, governance decay, and inequality. Yet Africa’s oil states have repeated the pattern with mechanical precision. The influx of petrodollars inflates exchange rates, undermines agriculture and manufacturing, and fosters an economy addicted to imports. When oil prices fall, entire nations plunge into fiscal crisis, revealing how little of their wealth was ever invested in resilience.

The IMF’s fiscal analyses consistently show that these countries spend lavishly in boom years, only to impose austerity when markets tighten. Citizens bear the whiplash of mismanagement—subsidies slashed, taxes raised, social services gutted. Meanwhile, the elite continue to thrive, cushioned by offshore accounts and foreign investments. The cycle repeats with every price shock, deepening a structural inequality that no election or reform slogan can erase.

But this is not only an economic failure—it is a moral one. When governments choose secrecy over transparency, they choose inequality over justice. When they treat oil as a tool of political survival rather than human development, they turn a blessing into a weapon. The wealth of the people becomes the poverty of the people. And the greater the wealth, the greater the poverty it produces.

The social consequences extend beyond material deprivation. Poverty in oil states is not just about income—it is about exclusion. Citizens are locked out of decisions about how their resources are managed. Public consultations are performative; community consent is assumed, not earned. The result is a populace alienated from its own wealth. The oil that was meant to unify nations instead divides them—by class, by geography, by access to power.