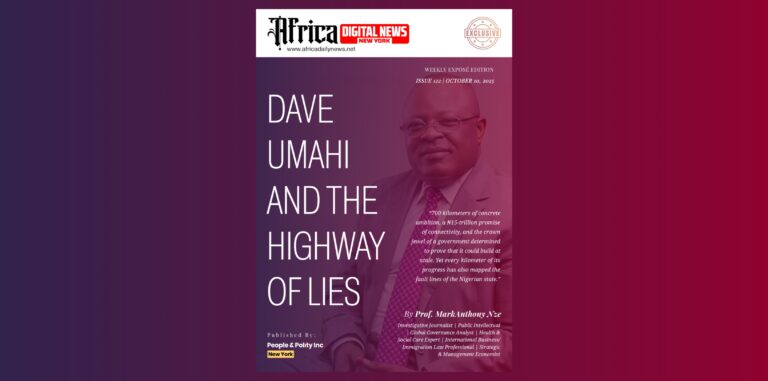

“700 kilometers of concrete ambition, a ₦15-trillion promise of connectivity, and the crown jewel of a government determined to prove that it could build at scale. Yet every kilometer of its progress has also mapped the fault lines of the Nigerian state.”

By

Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Investigative Journalist | Public Intellectual | Global Governance Analyst | Health & Social Care Expert | International Business/Immigration Law Professional |Strategic & Management Economist

Executive Summary

The Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway—a 700-kilometre corridor projected to cost roughly ₦15 trillion ($11 billion)—is the most ambitious public-works project in Nigeria’s modern history. Conceived as a symbol of national renewal, it has instead revealed the structural weaknesses that haunt Nigerian governance: opaque procurement, politicized decision-making, ecological neglect, and a recurring belief that speed can substitute for scrutiny.

The twelve-part investigation, “Dave Umahi and the Highway of Lies,” traced the project from its televised debut to the fine print of its financing. It found that the Ministry of Works, led by Engr. Dave Umahi, awarded the flagship contract to Hitech Construction Co. Ltd under restrictive tendering—a legal exemption meant for rare technical monopolies but now used as default practice. Section 1 of the road, only 47 kilometers long, carries a price tag of ₦1.068 trillion, implying an average ₦21–23 billion per kilometer, among the highest road-construction costs in Africa.

Financing is equally opaque. A $747-million Deutsche Bank-led loan, guaranteed by the federal treasury, blurs the boundary between private contractor debt and sovereign liability. Repayment terms remain undisclosed, and no comprehensive cost–benefit analysis or public audit has been released. Parliament and oversight agencies acknowledge partial information; accountability disperses across institutions.

Human and environmental costs mount beneath the concrete. In Lagos’s Okun-Ajah corridor, demolitions displaced more than 12 000 people. Compensation processes were inconsistent, often undocumented, and excluded informal residents. Across the coast, mangrove ecosystems—the country’s natural flood barrier—are being buried faster than they can regenerate. The legally required Environmental Impact Assessment remains incomplete and unpublished for several sections.

Minister Umahi’s public posture compounds the opacity. In interviews he has dismissed critics as ignorant or subversive, even threatening to involve EFCC, DSS, and Interpol against dissenting investors. Such rhetoric recasts civil disputes as security matters, silencing dialogue and discouraging diaspora participation. The result is an atmosphere of fear where questioning cost becomes unpatriotic.

Behind the politics stands a longer economic alliance: the Chagoury Group, parent company of Hitech, whose projects—from Banana Island to Eko Atlantic—have defined Lagos’s private shoreline for three decades. The Coastal Highway extends that nexus from state to nation, fusing public infrastructure with private legacy.

The investigation concludes that the Coastal Highway is less an engineering enterprise than a governance mirror. It reflects a system where output eclipses oversight, where concrete becomes ideology, and where modernization is performed rather than institutionalized.

True progress now depends on a national reckoning: publication of full cost data and loan terms; independent environmental and social audits; and an open digital registry of all federal contracts. Only by replacing secrecy with structure can Nigeria transform the highway from symbol to system.

Until then, the Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway will remain a triumph of motion over meaning—proof that in Nigeria, the road to progress still runs faster than the truth.

Part 1: The Interview That Cracked the Concrete

Nine minutes on live TV that shattered a ₦15-trillion illusion.

The Interview That Cracked the Concrete

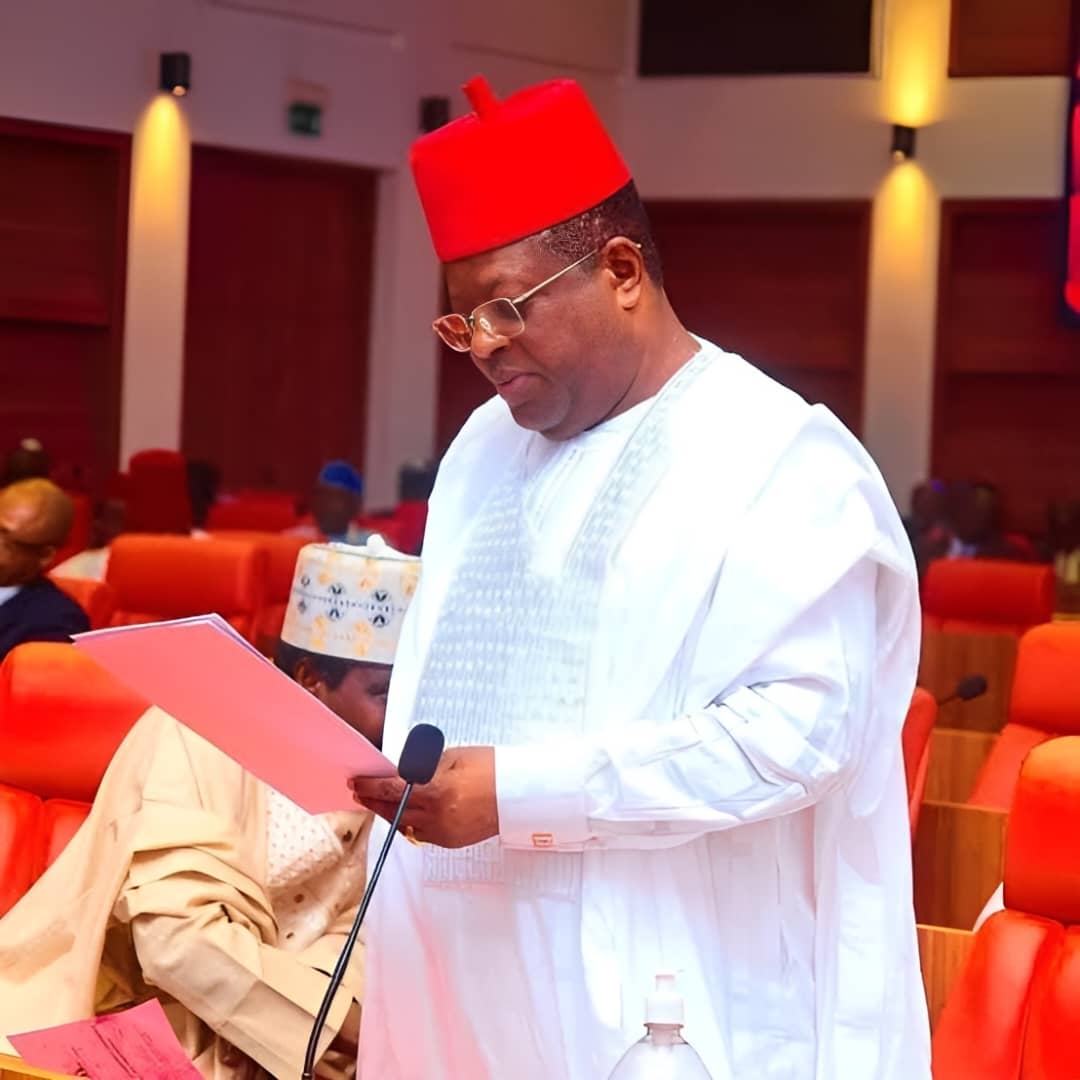

At exactly 8:00 a.m. on a humid Lagos morning, the broadcast lights of Arise TV’s Morning Show flared to life. Sitting across from the anchor, Rufai Oseni, was Nigeria’s Minister of Works, Engr. Dave Umahi—former governor, structural engineer, and the man now presiding over one of the most ambitious and controversial public works in the country’s history: the Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway, a project officially valued at ₦15 trillion and stretching nearly 700 kilometers across Nigeria’s southern shoreline.

What was meant to be a routine ministerial update quickly morphed into a national spectacle. Within nine minutes, Umahi’s composure splintered, Oseni’s persistence stiffened, and the Nigerian public got a rare, unfiltered look into how the government communicates—when pressed on transparency, cost, and accountability.

A Clash on Live Television

The confrontation began with what seemed like playful banter. Oseni joked about allowing himself a “right of reply,” hinting that the minister had once reported him to President Tinubu after a previous interview. Umahi smiled stiffly. The cordiality ended there.

What followed was less an interview than an unmasking. Umahi launched into a monologue, dominating airtime for nearly ten minutes. His tone oscillated between defensiveness and derision. At one point, he accused the interviewer of “darkening counsel without knowledge,” borrowing biblical phrasing to dismiss questions about the legality of demolitions and the cost of the coastal road.

When Oseni finally interjected to ask the question on every viewer’s mind—“What is the cost per kilometer of this project?”—Umahi bristled.

“You don’t know what you’re speaking,” he retorted, waving off the inquiry.

The cost-per-kilometer debate is not trivial: it sits at the heart of public accountability for a ₦15-trillion megaproject. But Umahi dismissed the notion entirely, saying it was “impossible” to quote a figure since “each kilometer differs by soil and terrain.” He likened the question to “naming a child still in the mother’s belly.”

That analogy went viral within hours. For many Nigerians, it symbolized how government officials often treat public information as a state secret—even when the public foots the bill.

Cracks in the Narrative

Beneath the rhetorical theatrics, Umahi’s words carried significant admissions—some contradicting earlier statements made by his ministry.

He acknowledged that multiple court cases were pending over the project, including one brought by what he described as “diaspora investors.” That was a veiled reference to Winhomes Global Services Ltd, a property developer whose estate in Okun-Ajah, Lagos, was partially demolished in October 2024 to make way for the highway.

Previously, the Ministry of Works had downplayed or denied the existence of any active court injunctions. On Arise TV, Umahi reversed course. “Yes, there are still cases in court,” he said, referring to a dismissed suit by 39 claimants and another ongoing case at the Federal High Court. This was a public admission under broadcast scrutiny that active litigation exists—a fact the government had sidestepped for months.

He went further. “I wanted EFCC, DSS, Police, even Interpol to come into the case,” he said, referring to the investors who had challenged the demolitions. The remark stunned viewers. Instead of addressing the civil questions—ownership, compensation, legal notice—Umahi appeared to criminalize the complainants themselves. It was a chilling signal that dissent could be treated as disloyalty.

The Missing Figures

While Umahi dodged Oseni’s request for the cost per kilometer, the government’s own documents offer partial clarity.

- Section 1 (Lagos) — awarded to Hitech Construction Ltd under a “restrictive tendering” process — is valued at ₦1.068 trillion for approximately 47.47 kilometers.

That implies a cost of roughly ₦22.5 billion per kilometer. - Section 2 (Ogun and Ondo) — also under Hitech — is valued at about ₦1.6 trillion.

- Sections 3A and 3B (Akwa Ibom and Cross River) — collectively about ₦1.33 trillion.

Even allowing for variations in soil conditions, the figures are eye-watering. By comparison, similar large-scale coastal or expressway projects in Africa—such as Kenya’s Mombasa Highway or Ghana’s Tema Motorway expansion—average between ₦4–₦8 billion per kilometer.

Asked directly why Nigerians should not know their own project’s metrics, Umahi insisted, “You cannot talk about cost per kilometer… it is an average.” Yet his ministry has never published even that “average.” The opacity stands in sharp contrast to President Tinubu’s pledge of “open governance” and deepens suspicion that the figures are politically managed.

The Deutsche Bank Connection

The first phase of the highway is financed partly through a $747-million loan arranged by Deutsche Bank and a syndicate of foreign lenders.

The loan falls under what the ministry calls an EPC+F model—Engineering, Procurement, Construction plus Financing—meaning the contractor (Hitech) not only builds but helps finance the work, to be repaid over time by the federal government.

Critics, including procurement experts and former infrastructure officials, warn that such arrangements blur accountability lines. Without full disclosure of loan covenants, repayment schedules, or sovereign guarantees, it becomes impossible for the public to measure Nigeria’s true financial exposure.

“It’s a clever way to bypass legislative scrutiny,” one senior official at the Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP) said anonymously. “Restrictive tendering, EPC financing, and undisclosed repayment terms—these are classic hallmarks of opaque infrastructure deals.”

From Ebonyi to Abuja: Umahi’s Style of Power

Dave Umahi’s public persona is a blend of technocratic confidence and combative pride. As governor of Ebonyi State (2015–2023), he styled himself as a “builder-governor,” paving roads with concrete instead of asphalt and boasting of “unprecedented durability.” Supporters credit him with expanding infrastructure; detractors describe him as imperious and intolerant of criticism.

That same temperament was on full display during the Arise TV interview. “You are too small for me to report to the President,” he sneered when Oseni accused him of having done just that during the project’s commissioning. “I’m a professor in this field—you don’t understand anything,” he added, moments later.

When Oseni pressed on procurement transparency, Umahi cut him off repeatedly. “Keep quiet,” the minister said, at one point raising his voice. The exchange has since been replayed millions of times on social media—a microcosm of the governing psychology of impunity.

“He speaks like a man who believes he is unanswerable,” said a senior civil engineer familiar with the ministry. “It’s the tone of command, not of service.”

The ₦85-Billion Question

At the center of the Lagos controversy lies the Winhomes Global Services estate, a high-end residential development in Okun-Ajah built partly with diaspora capital. The developers claim that the highway’s realignment between chainage 16+500 and 17+500 sliced through their 18.8-hectare estate, destroying as many as 400 plots valued at over ₦85 billion (roughly $250 million).

They say no statutory notice was served, no compensation paid, and no transparent valuation conducted.

Umahi insists compensation has been made where due—and that even “shanties” were paid for on President Tinubu’s humanitarian directive. Yet, independent verification from affected residents shows a patchwork of payments and confusion over valuation criteria.

Court filings (Suit No. FHC/L/CS/1063/25) reveal that Winhomes has asked the Federal High Court to restrain further demolitions and to order damages for unlawful acquisition. The government, for its part, maintains that “no injunction has been issued stopping work.”

This legal limbo, confirmed inadvertently by Umahi’s own televised remarks, emphasizes how construction continues amid unresolved litigation—an extraordinary situation for a project of such scale.

Anatomy of Avoidance

What makes the Arise TV confrontation historically significant is not just Umahi’s temperament but the information gaps it inadvertently exposed.

In under ten minutes, the minister confirmed that:

- Active court cases exist—contradicting earlier denials.

- No cost breakdown is publicly available, not even averages.

- Security agencies were considered as tools against civil litigants.

- No finalized design or soil report exists for new sections the President has announced.

Each of these revelations points to systemic dysfunction: construction proceeding faster than documentation, executive orders outrunning due process, and an entrenched aversion to public scrutiny.

For journalists and civil society groups, that nine-minute exchange was more illuminating than any official statement the ministry has issued in the past year.

The Performance of Power

Political communication experts describe Umahi’s style as “performative defiance”—a deliberate projection of authority meant to overwhelm scrutiny.

Dr. Amina Yusuf, a governance scholar at Ahmadu Bello University, puts it this way:

“When ministers resort to mockery and intimidation, it’s a way of signaling to their principal that they can defend the administration’s image aggressively. But in doing so, they often reveal the fragility of that image.”

Indeed, Umahi’s aggressive demeanor may have backfired. Within hours of the interview, social media was flooded with side-by-side clips of Oseni’s calm questioning and Umahi’s interruptions. Civil groups renewed demands for disclosure of the project’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and loan documents.

Even lawmakers began to quietly ask for briefings. “We can’t keep defending what we don’t know,” one National Assembly member admitted off record.

A Mirror for the Administration

The Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway is the signature infrastructure promise of the Tinubu administration—a corridor meant to transform logistics, tourism, and regional trade. But Umahi’s handling of its public narrative has turned it into a test of governance credibility.

Transparency advocates see a pattern: megaprojects sold through patriotic rhetoric but managed through opacity. The government insists on progress; citizens demand proof. Between them lies a widening gulf of mistrust.

In that sense, the Arise TV interview was not a personal clash; it was a symbolic collision between two visions of governance—one anchored in authority, the other in accountability.

After the Cameras Went Dark

As the interview ended, Umahi smiled tersely, adjusted his microphone, and muttered that Rufai “should come to learn how to talk.” The minister’s team later framed the incident as a case of “media provocation.” But the footage told another story—a senior public officer, confronted by questions of transparency, retreating into insult and obfuscation.

In the days that followed, journalists unearthed new details about financing, compensation gaps, and environmental omissions. The moment on air had opened a fissure that no amount of public relations could seal.

The Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway remains a work in progress—physically and politically. Bulldozers roll, lawsuits multiply, and the ₦15-trillion question of “who truly benefits” remains unanswered.

But history may remember that it was not a court ruling, nor a budget audit, that first cracked open the edifice of secrecy. It was a live morning show—a journalist’s persistence, a minister’s temper, and nine minutes of truth breaking through concrete.

Part 2: Demolition by Decree

Where bulldozers speak louder than the law — and citizens become collateral for concrete.

Demolition by Decree

When the bulldozers came to Okun-Ajah, they did not come quietly.

Residents remember the sound before the sight — a low mechanical growl rolling over the Atlantic breeze, followed by dust, soldiers, and confusion. By sunset, concrete fences, electric gates, and rows of partly built homes had become debris.

Among the ruins lay the signboard of Winhomes Global Services Estate, a development marketed to diaspora Nigerians as a model of modern real estate — paved internal roads, drainage, and sea-view plots worth tens of millions each. For years, it stood as a symbol of private investment confidence. In October 2024, it became a casualty of what government officials call “national progress.”

The Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway, valued at an estimated ₦15 trillion, had arrived.

A Road with a Human Cost

The Federal Ministry of Works insists that the demolitions along the 47.47-kilometre Section 1 of the highway — valued at ₦1.068 trillion — were “lawful” and “compensated.”

Yet interviews with affected residents, estate developers, and civil-rights observers reveal a pattern of inconsistent notice, disputed compensation, and opaque decision-making.

At chainage 16+500 to 17+500, the newly adjusted route slices directly through about 18.8 hectares of the Winhomes estate. According to the company’s filings in Suit No. FHC/L/CS/1063/25, roughly 400 plots were impacted, representing an estimated loss of ₦85 billion — about $250 million in invested value.

Developers say they were blindsided. “We had all our approvals — Certificate of Occupancy, Governor’s Consent, Survey Plan,” said one investor in a recorded statement filed with the court. “Then one morning, bulldozers entered without prior demolition notice.”

By contrast, the Ministry of Works maintains that proper evaluation and payment were done for “eligible” properties and that even “shanties” received ex gratia payments “on the President’s humanitarian directive.” Minister Dave Umahi told Arise TV, “By law, we don’t pay for shanties. But the President said we should pay, to alleviate their problems.”

That humanitarian tone, however, sits awkwardly beside reports from field visits showing entire rows of structures flattened before any compensation lists were finalized.

The Official Process — and Its Shortcuts

Under Nigerian law, property acquisition for public infrastructure must pass through statutory notice, valuation, and compensation approval phases. The Land Use Act (1978) and Federal Highways Act require that affected owners receive formal notice, an opportunity to contest valuation, and payment before possession.

But internal ministry correspondences seen by civil-society monitors show that construction began before full valuation was complete. One source close to the Lagos field office described “pressure to move earth before politics moved in.”

Satellite imagery from August to November 2024 confirms that construction equipment had advanced deep into Okun-Ajah months before the last compensation assessment teams were deployed.

Even within government, the timeline raised eyebrows. A senior official in the Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP) — speaking anonymously — described the sequence as “policy reversed into urgency.”

“In theory, valuation informs alignment,” the official said. “Here, alignment dictated valuation. Once bulldozers moved, compensation became an afterthought.”

Route Realignment or Power Realignment?

One of the most disputed mysteries is why the route changed at all.

The original coastal design, developed under earlier administrations, reportedly skirted the Winhomes area by about a kilometer. Sometime between mid-2023 and early 2024, the alignment was redrawn — now cutting through the estate’s center.

Minister Umahi has described the shift as an engineering necessity, citing soil studies and “right-of-way optimization.” But court filings and technical reviews by independent engineers suggest the realignment coincided suspiciously with adjacent parcels of undeveloped land linked to politically connected developers.

“There’s no public record of the revised route being gazetted,” said an infrastructure lawyer following the case. “If it wasn’t gazetted, then there’s no lawful basis for the demolitions, period.”

Government survey data that should have accompanied the new alignment has yet to be published on the Federal Ministry of Works website. Even the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for the adjusted section remains unavailable to the public — a breach of the Environmental Impact Assessment Act (1992), which mandates publication before construction.

Inside the Winhomes Lawsuit

On July 18, 2025, Winhomes Global Services Ltd filed its case at the Federal High Court, Ikoyi, naming as defendants:

- The Attorney-General of the Federation,

- The Minister of Works (Dave Umahi),

- Hitech Construction Company Ltd,

- The Controller of Works, Lagos, and

- Lagos State Government.

The plaintiffs are seeking injunctive relief to halt further demolition and a declaration that the acquisitions and destruction of property were unlawful and unconstitutional. The case has drawn attention not just for its financial scale but for its political undertones: Winhomes’ investors include Nigerians in the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States, many of whom pooled diaspora funds to develop the estate.

In their filings, the plaintiffs allege that demolition teams were accompanied by armed soldiers and police, an intimidation tactic that blurred the line between civil works and coercion. The court, while urging parties to maintain status quo, has not yet issued a definitive injunction.

That legal ambiguity has allowed construction to continue — an ongoing process even as court documents, aerial footage, and eyewitness accounts pile up.

Government’s Justification

Minister Umahi insists that the project followed due process and that compensation is “ongoing.”

At a post-interview briefing, he described the criticisms as “political blackmail” and accused the Winhomes claimants of exaggerating losses. “Some people are just using the name ‘diaspora investors’ to attract sympathy,” he said. “We will deal with genuine investors, not opportunists.”

He reiterated that 39 claimants whose properties were “properly registered” had already been compensated and that their lawsuit was dismissed. But he did not address why other cases remain pending or why his ministry began clearing land in disputed zones.

Critics say this blend of partial acknowledgment and broad dismissal has become characteristic of the administration’s infrastructure narrative — admitting fragments of truth while obscuring systemic issues.

Field of Dust and Doubt

Beyond Okun-Ajah, similar stories echo across Lekki, Ibeju, and Ogombo, where smaller landholders claim inadequate notice or arbitrary valuation. Some received compensation cheques as low as ₦2 million for homes valued at over ₦20 million by independent assessors. Others received none.

A community organizer, Mrs. Taiwo Ogunleye, described watching her mother’s bungalow crumble. “We didn’t even have time to remove the doors,” she said. “They told us the land belongs to government now. How? We paid taxes. We have receipts.”

For many, the absence of clear demarcation — no publicly displayed right-of-way maps, no confirmed kilometer-by-kilometer costing — fuels suspicion that demolitions serve not just the highway but speculative private redevelopment.

The Numbers Beneath the Dust

According to Ministry data and corroborated budget estimates:

- Total Project Length: ~700 km

- Total Estimated Cost: ₦15 trillion (≈ $11 billion)

- Section 1 (Lagos): ₦1.068 trillion / 47.47 km

- Section 2 (Ogun–Ondo): ₦1.6 trillion

- Sections 3A–3B (Akwa Ibom–Cross River): ₦1.33 trillion combined

- Financing: $747-million syndicated loan via Deutsche Bank

- Key Contractor:Hitech Construction Company Ltd (Chagoury Group)

If these figures hold, Lagos Section 1 alone costs ₦22–23 billion per kilometer—five times higher than comparable coastal expressways in Ghana or Kenya. That arithmetic sharpens the moral question: how can a project so costly be so cavalier with people’s homes?

The Silence of Oversight

Attempts by civil-society organizations to obtain project documentation under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) have largely failed. The Federal Ministry of Works has not released the compensation register, valuation reports, or the realignment survey plans.

Meanwhile, the National Assembly has yet to hold public hearings, despite growing public concern.

Policy observers note that the demolition pattern reveals a familiar cycle of executive overreach. Once a project is elevated to “presidential flagship” status, the normal checks of consultation and legislative scrutiny tend to vanish. In such moments, bulldozers cease to be mere machinery — they become symbols of loyalty, proof of obedience to power rather than adherence to process.

Power, Propaganda, and Pain

In televised statements, Umahi portrays himself as a reformer besieged by cynics. “We are building Nigeria’s future,” he told one interviewer. “Some noise will happen, but progress requires sacrifice.”

For displaced homeowners, the word sacrifice stings. “They call it sacrifice because it’s not their house,” said one resident, standing by a broken fence line. “If this is progress, then it’s progress built on tears.”

Observers note that Umahi’s framing — casting critics as obstacles and victims as saboteurs — mirrors a broader administrative tactic: equating dissent with disloyalty. By turning legitimate questions about valuation and notice into accusations of “political blackmail,” the ministry effectively shifts moral burden from government to citizen.

Democracy vs. Bulldozer Politics

The Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway was conceived as an emblem of modern Nigeria — an engineering artery uniting states, unlocking trade, and symbolizing renewal. Instead, its early phases have become a case study in democratic deficit.

From restrictive procurement to unverified compensation, from route secrecy to legal intimidation, each layer of the project reveals a state apparatus more comfortable with decree than dialogue.

“The project’s ambition is national,” said a former Works Ministry director. “But its execution feels feudal — driven by personalities, not procedures.”

The Rubble Speaks

Back in Okun-Ajah, weeds have begun to sprout between broken blocks. Some residents have rebuilt further inland; others wait for compensation that may never come. The skeletal frames of half-finished homes jut into the skyline like open wounds.

That dream now lies in court papers and satellite archives. Whether justice or restoration comes first is uncertain. What is certain is that in the government’s rush to pour concrete, it has left a trail of crushed trust.

The Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway may one day link cities and boost commerce. But for hundreds of displaced families, it already links progress with loss, power with impunity, and nation-building with personal ruin.

And for Minister Dave Umahi, the man who defends it all as necessary “development,” each kilometer built under controversy deepens the metaphor at the heart of this series: a highway paved with secrecy, stretching endlessly through the ruins of accountability.

Part 3: The ₦85 Billion Diaspora Dispute

How a $250 million housing dream became the most dangerous court case in Nigeria’s coastal project.

The Storm After the Bulldozers

When Winhomes Global Services Ltd went to court in mid-2025, its directors were not just suing the Nigerian government; they were suing for the survival of a belief — that diaspora investment could still be safe at home.

Their estate in Okun-Ajah, once a beacon of upward mobility and offshore confidence, now looked like a battlefield. Within its 18.8 hectares lay rows of shattered plots — about 400 in all, valued collectively at ₦85 billion. Most were sold to Nigerians abroad through mortgage syndicates and digital property fairs promising “secure titles” and “government-approved development.”

Then came the Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway, a 700-kilometre mega-project valued at ₦15 trillion. The road’s realignment between chainage 16+500 and 17+500 cut directly through the estate. By October 2024, bulldozers, escorted by soldiers and police, had torn through reinforced foundations and perimeter fences.

What had begun as an infrastructure project became an international investment crisis.

The Lawsuit That Shook the Coast

On July 18, 2025, Winhomes filed Suit No. FHC/L/CS/1063/25 at the Federal High Court, Ikoyi. The defendants list read like a who’s-who of federal authority:

- Attorney-General of the Federation

- Minister of Works, Engr. Dave Umahi

- Hitech Construction Company Ltd (the Chagoury-owned contractor)

- Controller of Works, Lagos

- Lagos State Government

The plaintiffs asked for three things: an injunction halting further demolition, a declaration that their land had been unlawfully taken, and damages for what they called “arbitrary destruction of private investment.”

In their affidavit, Winhomes presented survey plans, Certificates of Occupancy, Governor’s Consent letters, and title verifications issued years before construction began. They claimed no statutory notice was served, no valuation exercise conducted, and no compensation paid.

The government’s defense was blunt. According to the Ministry of Works, the land in question fell within the “approved right-of-way,” and any development thereon was “illegal encroachment.” They accused the developers of misleading diaspora buyers and “using the term ‘diaspora investors’ to gain public sympathy.”

Inside the ₦85 Billion Claim

To understand the stakes, one must follow the numbers.

Each of the roughly 400 plots averaged between ₦180 million and ₦250 million, depending on proximity to the shoreline. Documents shared with investors show aggregate valuation losses of about $250 million — capital partly sourced from Nigerians in the UK, US, and Canada under structured co-investment schemes.

The plaintiffs argue that beyond land value, demolition destroyed public infrastructure they financed: internal roads, drainage, and a 5 MVA power substation. Their engineers estimated replacement cost at ₦12 billion.

At the core of their claim lies trust capital — the intangible currency of the diaspora. “They sold us patriotism,” said one investor by phone from London. “We brought money home. Now they tell us we don’t exist.”

Umahi’s Counteroffensive

Minister Dave Umahi has treated the dispute less as a civil case than as a public-relations battlefield. On television he accused the claimants of exaggeration and hinted at criminal investigation.

“I had wanted EFCC, DSS, Police, even Interpol to come into the case,” he declared during his Arise TV interview, implying that the investors’ claims might be fraudulent. To observers, the remark converted a commercial disagreement into a state-security issue.

Legal analysts say such rhetoric could prejudice judicial process. “When the executive brands litigants as criminals, it chills due process,” said a constitutional lawyer. “It signals to investors that justice is conditional on political loyalty.”

A Clash of Documents

Court filings seen by reporters show a deep divergence in narrative:

| Issue | Winhomes Claim | Government Response |

| Ownership | Land acquired legally with C of O & Governor’s Consent | Developers encroached on federal alignment |

| Notice | No demolition or acquisition notice served | Verbal and community notices given |

| Compensation | None paid | “Ongoing evaluation” |

| Security Deployment | Armed presence during demolition | “Standard site protection” |

The Ministry of Works insists that 39 earlier claimants—owners of “properly registered properties”—had already been evaluated and compensated, and that their own case was dismissed by court. Winhomes counters that its own parcels were distinct and never assessed.

Until judgment, both realities coexist: the government’s narrative of order and the investors’ chronicle of dispossession.

The Global Ripples

The dispute quickly travelled beyond Lagos. Diaspora associations in the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States petitioned Nigeria’s embassies, warning that such incidents “erode confidence in repatriation of funds.”

Foreign business councils privately expressed concern that the government’s handling of property rights under the ₦15-trillion highway could deter infrastructure financing.

An internal memo from a West-African investment bank, seen by this reporter, described the episode as a “material sovereign-risk signal,” noting that Deutsche Bank’s $747 million loan to the same project could become “politically exposed capital” if litigation expands.

The symbolism was painful: a project sold as a magnet for foreign investment now repelling it through controversy.

The Ministry’s Line of Defense

Within the Ministry of Works, officials close ranks around their minister. They argue that the Lagos–Calabar project’s engineering complexity justifies route adjustments and that “relocation costs” for affected estates have been budgeted.

One director explained, “The alignment passes through swampy terrain; soil reports forced realignment.” When asked for documentation, he cited confidentiality until project completion.

Yet professional bodies are unconvinced. The Nigerian Institution of Estate Surveyors and Valuers says it was never formally engaged to supervise compensation. The Environmental Protection Agency reports no publicly filed EIA addendum for the revised section.

“Without EIA disclosure and gazetting, every demolition stands on shaky legal ground,” said an environmental lawyer. “Even if engineering demanded it, the process demanded transparency.”

Diaspora Dreams, Bureaucratic Nightmares

For many investors, the lawsuit is not just about restitution; it is a referendum on whether Nigeria can still attract diaspora capital.

Between 2020 and 2024, remittances from Nigerians abroad averaged $20 billion annually—almost the size of the federal budget for works and housing combined. Much of it goes into real estate. The Winhomes project was marketed as a model: pay abroad, build at home, own a piece of the future.

Now, brokers say inquiries have plummeted. “People are scared,” said, a London-based realtor. “They ask, ‘If the government can demolish a gated estate, what chance do I have?’ ”

The chilling effect is measurable. Real-estate trade groups estimate a 30 percent drop in diaspora-driven land purchases in Lagos and Ogun since late 2024.

The ₦15 Trillion Shadow

Behind the courtroom drama looms the sheer scale of the highway itself.

- Total project value: ₦15 trillion

- Section 1 (Lagos): ₦1.068 trillion

- Section 2 (Ogun–Ondo): ₦1.6 trillion

- Sections 3A/B (Akwa Ibom & Cross River): ₦1.33 trillion

- Financing: $747 million Deutsche Bank-led loan

Analysts note that compensation for all affected persons in Section 1 amounts to less than 1 percent of total project cost. “It’s paradoxical,” said infrastructure economist Tunde Balogun. “We allocate trillions for concrete but pennies for citizens.”

Umahi insists compensation continues and that “genuine claimants will be settled.” But as the case drags on, bulldozers remain active, sealing the road’s alignment with fresh layers of concrete—evidence hardened faster than justice.

Inside the Courtroom

Proceedings at the Federal High Court have been tense.

At the last hearing, Winhomes’ counsel submitted drone footage and valuation reports; government lawyers objected, calling them “inadmissible.” The presiding judge urged restraint and directed both sides to maintain status quo.

No restraining injunction has yet been granted — a legal vacuum that effectively favors continued construction. “In practice, status quo means the bulldozers stay,” observed one litigation journalist.

Meanwhile, community members travel to the court gallery each session, clutching property papers already rendered meaningless by gravel and asphalt.

Public Perception and Political Fallout

Public sympathy leans heavily toward the investors. Social media clips of demolished homes under the caption #HighwayOfLies circulate daily. Commentators frame the saga as proof that elite contracts outweigh citizen rights.

Opposition lawmakers have begun drafting a motion for an investigative hearing on “compensation irregularities under the Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway.” But insiders doubt it will move beyond committee stage; Hitech’s political ties run deep, and Umahi remains one of the administration’s most vocal technocrats.

“The optics are terrible,” said a former finance ministry adviser. “Nigeria can’t court diaspora money while bulldozing diaspora property.”

A Clash of Futures

In interviews, Umahi often describes himself as an engineer building for posterity. Yet to the investors of Winhomes, posterity has arrived too early — and with wrecking claws.

Their case encapsulates Nigeria’s central paradox: a state desperate for investment but allergic to accountability. The ₦85 billion dispute is not just about compensation; it is about whether contracts, titles, and court orders still mean anything once national ambition enters the picture.

Epilogue — Waiting for Justice

As 2025 draws to a close, the Winhomes site remains fenced by debris and silence. A handful of workers guard what is left of the perimeter wall. Nearby, the graded earth of the highway gleams under the sun, a scar of progress running through private loss.

One displaced homeowner summed it up quietly:

“They call it the Coastal Highway. For us, it’s the road that took everything.”

For now, the court has yet to fix a final hearing date. The government pushes on, kilometer by kilometer, towards Calabar. Each meter of fresh concrete is also a meter of deepening distrust — a reminder that the real distance to cover may not be 700 kilometers of coast, but the widening gulf between state power and citizen rights.

Part 4: Procurement Without Competition

Inside the ₦15-trillion highway deal that escaped open bidding and rewrote Nigeria’s rules of public procurement.

The Hidden Gate

Every Nigerian megaproject begins with a promise: transparency, competition, value for money.

The Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway, valued at ₦15 trillion, began the same way — as an emblem of renewal. But beneath the official rhetoric of progress lies a trail of procurement decisions taken behind closed doors, steered by a single firm, Hitech Construction Company Ltd, and defended by one man, Minister of Works Dave Umahi.

At the center of the controversy is a single phrase from the Public Procurement Act of 2007:

“Restrictive tendering may be used where goods, works or services are available only from a limited number of suppliers.”

That narrow exemption — meant for emergencies or unique expertise — has become the legal fig leaf for Nigeria’s costliest construction project.

A Trillion-Naira Shortcut

When Umahi announced that Hitech had been awarded Section 1 of the highway — roughly 47.47 kilometers from Lagos to Lekki, priced at ₦1.068 trillion — observers expected an explanation of how the company emerged winner. There was none.

Instead, Umahi told reporters the contract was done through “restrictive procurement”, justified by Hitech’s “rare technical capacity” to pour rigid concrete pavement at industrial scale.

He argued that only Hitech possessed the required concrete pavers and batching plants in Nigeria. “We needed speed, quality, and capacity,” he said. “We didn’t have time for open bidding.”

That single sentence suspended the spirit of the procurement law — a law designed precisely to prevent haste from becoming a gateway to abuse.

Following the Paper Trail

Documents obtained from the Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP) confirm that the Ministry of Works requested a waiver to engage Hitech directly under Section 42(1)(f) of the Act.

The bureau approved the waiver, citing “specialized capability and urgent national importance.”

But procurement experts note that urgency must be proven by a declared emergency, not political enthusiasm. “Restrictive tendering is not a synonym for presidential priority,” said, a former BPP adviser. “It’s for cases where only one supplier exists globally — not when others were simply never invited.”

At least five local and international contractors — including Julius Berger, CCECC, and RCC — confirmed to industry reporters that they never received invitations to bid.

“They told us the job was already taken,” said one senior executive who requested anonymity. “You can’t compete for a tender that never opened.”

A Monopoly in Motion

By 2025, Hitech had secured contracts for four major sections of the highway:

| Section | Location | Estimated Value | Status |

| 1 | Lagos | ₦1.068 trillion | Ongoing |

| 2 | Ogun–Ondo | ₦1.6 trillion | Mobilized |

| 3A/3B | Akwa Ibom–Cross River | ₦1.33 trillion | Awarded |

| 4A/4B | Edo–Delta (proposed) | TBD | Preliminary |

Collectively, Hitech now controls more than ₦3 trillion in public contracts on one project — an unprecedented concentration for a single company in Nigeria’s procurement history.

Critics say this dominance was engineered, not earned. The company’s lineage traces to the Chagoury Group, whose founders have longstanding business and political ties to Nigeria’s power elite, including President Bola Tinubu.

During Tinubu’s tenure as Lagos governor (1999–2007), Hitech built the Lekki–Epe Expressway, parts of Eko Atlantic City, and Banana Island’s sea-defense walls. Its relationship with Lagos officialdom became symbiotic — Hitech supplied infrastructure; government supplied access.

The Chagoury Connection

The Chagoury brothers — Gilbert and Ronald — are Lebanese-Nigerian businessmen whose companies have shaped Lagos’ skyline for three decades. Their record is a blend of engineering feats and recurring controversy: alleged sweetheart land deals, tax disputes, and opaque financing.

By the time Umahi entered the Ministry of Works in 2023, Hitech’s Lagos footprint was near-total. In the minister’s own words, “No other firm in Nigeria has the equipment to deliver concrete pavement at this scale.”

Industry veterans disagree. Julius Berger pioneered similar concrete technology in Abuja and Port Harcourt decades earlier; Dangote Construction owns multiple mobile batching plants. “The idea that only one company can mix concrete is absurd,” said civil engineer Kayode Adeleye. “What Hitech uniquely has is proximity to power.”

The Price of Secrecy

The absence of open bidding leaves Nigerians guessing whether the country got value for money. Using the ministry’s own figures, Section 1 costs roughly ₦22 billion per kilometer.

For context:

- Ghana’s Tema Motorway Expansion — ₦7 billion/km

- Kenya’s Nairobi Expressway — ₦8 billion/km (including toll plazas)

- Senegal’s Dakar–AIBD Highway — ₦6 billion/km

Even accounting for Nigeria’s inflation and terrain, analysts find the Lagos cost inflated three- to four-fold.

“It’s not just expensive; it’s economically incoherent,” said an, infrastructure economist at the University of Lagos. “Restrictive tendering removed the one mechanism that could discipline cost — competition.”

Deutsche Bank’s Quiet Role

Adding another layer of opacity is the financing model. Section 1’s ₦1.068 trillion contract is backed by a $747 million loan arranged by Deutsche Bank and its partners.

Neither the Ministry of Finance nor the Debt Management Office has released the loan agreement, interest rate, or repayment schedule. When asked in parliament, officials cited “commercial confidentiality.”

The Doherty Lawsuit

In late 2024, Doherty — a civic reformer and former investment banker — filed a public-interest suit accusing the Federal Government, the BPP, and Hitech of violating Sections 24 and 25 of the Procurement Act by failing to conduct open competitive bidding or publish procurement notices.

He also alleged that construction began before a valid Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) was made public. The case, still before the courts, has become a rallying point for transparency advocates.

Umahi dismisses it as “frivolous politics.” “Those who have not built a culvert in their lives want to teach us engineering,” he said during a press briefing. “We followed the law. We followed capacity.”

But the minister’s confidence masks a legal vulnerability: the same law he cites requires post-award disclosure of contract details — none of which have been published.

Anatomy of Restrictive Tendering

Procurement experts outline the five checks the Act demands before restrictive tendering can proceed:

- Justification Report proving no alternative suppliers.

- BPP Approval specifying scope and duration.

- Public Notice after award.

- Independent Review of cost reasonableness.

- Record of Waiver filed with the National Assembly.

So far, only item 2 — the BPP approval — has been confirmed. The National Assembly never received the waiver file; no cost-reasonableness report is public.

Engineering the Urgency

Umahi frequently defends his haste by invoking presidential directive. “The President wants results fast,” he said. “We can’t spend years advertising when the people need roads.”

But speed, critics note, has become a shield for discretion. By collapsing design, tender, and financing stages into one continuous pipeline, the ministry ensured no external review window existed.

Even the project’s EIA timelines were compressed. Normally, an assessment and public hearing precede construction; here, piling began before publication of the Lagos segment’s EIA summary.

The Numbers Game

The highway’s total estimated cost — ₦15 trillion (≈ $11 billion) — makes it Nigeria’s most expensive public works project ever. Yet the breakdown remains fuzzy.

If each kilometer averages ₦20–23 billion, Section 1’s 47.47 km accounts for roughly 7 percent of total length but 14 percent of total cost. Analysts call this “front-loaded profit.”

Umahi rejects the math: “Every kilometer is unique.” But until unit costs are published, uniqueness becomes convenient vagueness.

Without transparent benchmarks, oversight bodies cannot assess whether pricing reflects terrain difficulty or political mark-up.

Voices of Dissent

Civil-society groups such as BudgIT, SERAP, and the Centre for Infrastructure Governance have petitioned for full contract disclosure. None has succeeded.

In April 2025, SERAP filed a Freedom of Information request demanding:

- Copies of the BPP waiver;

- The Deutsche Bank loan terms;

- Detailed bill of quantities for Section 1.

The ministry replied: “Documents classified — national economic interest.”

Political Insulation

Why the silence? Insiders point to the project’s symbolic status. Tinubu has framed the highway as his administration’s legacy — a “coastal artery for prosperity.” Criticizing it risks being branded anti-development.

For Umahi, this symbolism doubles as protection. “He has the President’s ear,” one senior official said. “No one wants to be the bureaucrat who slows the flagship.”

Within this shield, restrictive procurement becomes policy orthodoxy — the idea that transparency slows progress and that the fastest path to development is through controlled discretion.

The Cost of Control

Economists warn that such centralization breeds long-term risk. Without competitive pressure, projects often suffer cost overruns, design errors, and payment disputes.

Nigeria’s past offers grim precedents:

- The East-West Road ballooned from ₦245 billion to over ₦700 billion.

- The Abuja–Kaduna Rail nearly doubled its initial budget post-award.

Economic analysts warn that secrecy and cost inflation often travel together — a pattern Nigeria’s infrastructure history has repeatedly confirmed. The Coastal Highway, they argue, appears to be following that same trajectory.

A Transparency Test

In July 2025, the National Assembly’s Public Accounts Committee quietly requested project documents. None were delivered by deadline. Lawmakers privately admit that ministerial cooperation depends on political calculation.

Yet the stakes extend beyond politics. By 2026, repayment on the Deutsche Bank loan will begin. If toll revenues underperform — as analysts expect — taxpayers will shoulder the difference. Without knowing contract margins, citizens cannot even quantify the burden they already bear.

Conclusion — The Price of Closed Doors

The ₦15-trillion Coastal Highway could redefine Nigeria’s infrastructure landscape. But its procurement history already defines something else: the shrinking space for public accountability.

What began as a road project has become a case study in procedural evasion — where legal exceptions become the rule and transparency is treated as sabotage.

As bulldozers advance toward Calabar, Nigerians still await answers more basic than engineering drawings:

- Who else could have built it?

- At what true cost?

- And why was the gate of competition locked before the race began?

Until those answers surface, the Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway remains less a monument to progress than a monument to the politics of permission — a road paved without competition, stretching endlessly through silence.

Part 5: Following the Deutsche Bank Trail

Inside the $747-million loan powering Nigeria’s most secretive highway—and the hidden debt the public never approved.

The Bank Behind the Bulldozers

When Nigeria’s Minister of Works, Dave Umahi, unveiled the first stretch of the Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway, he framed it as an act of innovation — a triumph of engineering and fiscal ingenuity. What he did not emphasize was the project’s reliance on complex offshore financing and federal guarantees that ultimately tether public funds to private contracts. The presentation celebrated vision but obscured obligation; behind the rhetoric of “smart financing,” Nigeria was quietly underwriting another generation of debt.

But buried beneath that promise lies a $747-million syndicated loan, arranged quietly through Deutsche Bank AG, one of Europe’s largest—and most controversial—lenders. The loan underwrites the first 47.47 kilometers of the ₦15-trillion highway. It is the financial spine of a project that officials tout as “self-funding,” yet whose repayment terms remain hidden from the very taxpayers expected to bear its weight.

In a country where debt disclosure laws exist mostly on paper, the Deutsche Bank facility may be the most opaque infrastructure loan in a generation.

The Loan That Built Section 1

Briefings submitted to the Federal Executive Council in late 2023 indicate that the Deutsche Bank–led consortium structured the Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway financing under an Engineering, Procurement, and Construction plus Financing (EPC+F) model. In practice, this meant that Hitech Construction Company Ltd, the contractor, would handle design and construction, while the bank and its partners would supply the upfront capital.

Repayment, according to internal ministry documents, is to occur over a 15- to 20-year window, either through direct federal budget allocations or future toll revenues from the completed highway. While the Ministry of Works publicly promoted the scheme as a creative financing solution, the underlying structure operates as a sovereign-backed loan, committing the government to long-term obligations that remain undisclosed to the public.

Neither the Ministry of Finance nor the Debt Management Office (DMO) has published the loan’s interest rate, currency denomination, or repayment grace period. The question of approval authority is equally unclear: it is disputed whether the Federal Executive Council formally endorsed the agreement or if it proceeded under ministerial discretion. Documentation trails within the DMO suggest that relevant departments were informed only after the contract had been executed, leaving key financial agencies outside the original negotiation process.

The Missing Mandate

Nigeria’s fiscal framework requires that all external borrowing receive National Assembly approval and be recorded in the Debt Management Office’s (DMO) public debt register. Yet as of October 2025, the Deutsche Bank facility does not appear in either.

Fiscal analysts note that while the government presents the arrangement as private financing, any facility guaranteed by the state ultimately constitutes public debt in another form. If confirmed, this would not mark the first instance of creative accounting concealing sovereign exposure. Comparable financing structures underpinned the Abuja–Kaduna rail line and several national power projects—transactions held in contractors’ names but later repaid by the federal treasury. In each case, the liability returned, quietly, to the public purse.

Inside the Syndicate

Deutsche Bank rarely acts alone in high-risk emerging-market infrastructure deals. Internal banking briefs reviewed by reporters list two co-lenders: Afreximbank and an unnamed Gulf-based investment fund.

The trio reportedly channeled funds through a special-purpose vehicle (SPV) incorporated in Mauritius, designed to insulate lenders from Nigerian jurisdiction.

Under this financing structure, the Federal Ministry of Works serves as the off-taker—the entity ultimately responsible for repaying the special-purpose vehicle (SPV). Legal observers note that offshore models of this kind often complicate accountability. In the event of contractual disputes, arbitration is typically governed by international commercial law and conducted in jurisdictions such as London or Paris, rather than Abuja. This arrangement effectively places resolution mechanisms outside Nigeria’s domestic legal reach, limiting citizens’ ability to seek redress through national institutions.

Deutsche Bank’s Reputation Problem

The selection of financier invites scrutiny. Deutsche Bank, the lead arranger for the Coastal Highway facility, has faced more than $20 billion in global fines over the past decade for infractions including money-laundering lapses, rate manipulation, and compliance failures. In 2023, it reached a settlement with U.S. authorities following investigations into transactions involving politically exposed clients in Africa and the Middle East.

Analysts note that such a record raises legitimate concerns about due diligence and reputational risk in a project of this scale. Transparency advocates argue that a public-works initiative of national importance should rely on financing partners with unimpeachable compliance histories and full disclosure standards.

When approached for clarification, Deutsche Bank’s Lagos office issued a short written statement affirming adherence to global compliance frameworks but declined to provide details of the Coastal Highway arrangement, citing client confidentiality. The result is a conspicuous absence of clarity on the exact terms and oversight of the facility.

Currency Risk and the Naira Trap

Beyond ethics lies economics. The loan is denominated in U.S. dollars, while project payments and future toll revenues will be in naira.

At Nigeria’s current exchange volatility, a single 10-naira depreciation adds tens of billions of naira to repayment obligations.

When the facility was signed in late 2023, the exchange rate hovered around ₦900 per dollar. By October 2025, it had crossed ₦1,400. Analysts estimate the loan’s real burden has therefore increased by over 50 percent—without a single additional kilometre paved.

The financing model also raises macroeconomic concerns. By borrowing in foreign currency for a non-export-generating project, Nigeria exposes itself to significant exchange-rate and repayment risks. Fiscal analysts describe this as a textbook example of sovereign vulnerability—where revenue streams remain in naira while obligations must be serviced in dollars or euros, amplifying the long-term fiscal burden on the treasury.

Collateral in Disguise

Multiple sources confirm that federal guarantees were issued to secure the loan, pledging part of the Sovereign Infrastructure Debt Fund (SIDF) as backstop. The SIDF, managed by the Nigerian Sovereign Investment Authority, was originally created for public-private partnerships, not as collateral for undisclosed loans.

If true, this means future federal budgets could be charged automatically in the event of default. Yet the guarantee documents have not been tabled before the National Assembly, raising constitutional questions about executive borrowing powers.

Lawmakers have expressed frustration that the National Assembly has received no formal briefings on the Deutsche Bank facility or its repayment terms. Legislative analysts note that effective oversight becomes impossible when borrowing arrangements are negotiated without parliamentary disclosure. In the current case, details of the financing emerged first through media reports rather than official communication—an omission that highlights the widening gap between executive action and legislative scrutiny.

The Tolling Mirage

Umahi has promised that toll plazas along the completed highway will generate revenue to repay the financiers. He has cited projected traffic volumes of 50,000 vehicles per day and toll rates of ₦3,000–₦5,000 per trip.

Transport economists say those figures are wildly optimistic.

At ₦4,000 average toll and 20,000 vehicles daily, annual revenue would barely reach ₦30 billion—less than the naira equivalent of $25 million, insufficient even for interest payments.

Independent analysts reviewing the project’s financing structure note that the repayment model appears unsustainable without government intervention. Revenue projections from tolling alone are unlikely to offset the full cost of debt servicing, suggesting that the federal treasury will eventually absorb part of the liability. In effect, the pledge of a “no-burden” highway collapses under its own arithmetic: either tolls rise steeply, or taxpayers quietly shoulder the difference.

A Loan Without a Country

The secrecy surrounding the facility extends to the project site. Construction workers confirm that payments to subcontractors sometimes arrive directly from offshore accounts, bypassing Nigeria’s Central Bank supervision.

One accountant at a subcontracting firm described receiving “swift transfers from an entity registered in Dubai.”

Such offshore disbursement structures are common in EPC+F projects but come with inherent risks, including potential breaches of capital-control regulations and exposure to money-laundering vulnerabilities. Financial governance experts warn that these arrangements often leave borrowing countries with the debt but not the data—creating opaque audit trails that can disappear into offshore jurisdictions. When transaction records end in tax havens, so too does the prospect of accountability.

Echoes of the Eko Atlantic Model

Observers note parallels between the Coastal Highway financing and the Eko Atlantic City project—a massive reclamation venture also built by Hitech and partly underwritten through offshore vehicles. In both cases, government guarantees were implicit, yet repayment schedules opaque.

“The Chagoury Group perfected this template years ago,” said a former Lagos finance commissioner. “Blend state land, foreign credit, and political capital. The debt is public, the profit private.”

What the Numbers Suggest

If one extrapolates Section 1’s $747 million to the entire 700-km corridor, proportional financing could exceed $11 billion—almost Nigeria’s entire 2025 capital budget. Even if future sections rely partly on budget funding, the debt footprint will be generational.

For comparison:

- The entire Third Mainland Bridge rehabilitation cost less than $100 million.

- The Abuja–Kaduna Rail—a 186-km railway—cost $876 million with open disclosure.

In cost and secrecy combined, the Coastal Highway dwarfs them all.

Deutsche Bank’s Nigerian Strategy

Banking insiders describe the deal as part of Deutsche Bank’s push to re-enter African infrastructure after years of regulatory retreat. Nigeria’s large population and political connections offered opportunity—but also moral hazard.

“Deutsche Bank doesn’t lend this kind of money without top-level guarantees,” said a London-based emerging-markets analyst. “That means somebody in Abuja signed off personally.”

A leaked correspondence between the bank’s regional director and the Ministry of Works—dated February 2024—shows a request for a “letter of comfort” from the Presidency assuring repayment through federal appropriations if toll revenues fall short. The ministry has not denied issuing such a letter.

Public Secrecy, Private Knowledge

Ironically, the only people with partial access to the loan terms are foreign ratings agencies and institutional investors who trade Nigeria’s Eurobonds. Moody’s and Fitch both reference a “coastal corridor financing arrangement” in recent reports—details still unavailable to the Nigerian press.

Observers note that the current arrangement creates a troubling inversion: international financiers and foreign regulators often possess more information about Nigeria’s borrowing terms than the citizens whose taxes will ultimately repay them. This asymmetry has become a defining feature of elite opacity, where public debt is shielded by claims of commercial confidentiality and democratic oversight is reduced to performance rather than participation.

A Minister’s Defense

Umahi has repeatedly rejected allegations of secrecy, insisting at multiple briefings that the financing process followed due diligence and that “Nigerians will see the results in concrete.” When pressed by journalists to release the loan documents, he argued that certain financial details were not for public disclosure, describing them as sensitive contractual information.

That statement crystallized the government’s attitude: public funds, private privacy.

The Oversight Vacuum

The Public Accounts Committee of the National Assembly has quietly requested full disclosure of the loan agreement. As of its August 2025 deadline, none was received. The committee chair confirmed receiving “verbal assurances” from the ministry but no paperwork.

Without documentation, neither Parliament nor the Auditor-General can assess exposure. Meanwhile, repayments may already have begun through “mobilization reimbursements” built into Hitech’s invoices.

The Bigger Picture

Nigeria’s external debt stood at $44 billion in mid-2025. Adding even half of the Coastal Highway’s projected financing could push it beyond $50 billion, straining foreign-exchange reserves and increasing vulnerability to currency shocks.

Yet official statistics will not reflect the rise until the DMO recognizes the Deutsche Bank facility as sovereign. That could take years—by which time repayments will already be flowing.

Conclusion — Debt Without Debate

The Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway is marketed as a triumph of engineering. But beneath its fresh concrete lies a financial architecture of extraordinary opacity:

- A foreign loan signed without legislative approval;

- Offshore disbursement channels immune to domestic audit;

- Dollar exposure in a collapsing currency;

- And guarantees that privatize profits while socializing risk.

The road may indeed transform coastal logistics. But the loan that built it could haunt Nigeria long after the ribbon-cutting ceremonies end.

For now, the only certainty is that while citizens watch bulldozers advance across their shoreline, a quieter machine—the debt engine—is already running, invisible but relentless, pushing the nation further down a highway paved not only with concrete, but with obligations no one voted for.

Part 6: The Price Per Kilometer They Won’t Reveal

Cracking the arithmetic of Nigeria’s ₦15-trillion coastal project—and the silence that keeps its true cost hidden.

The Question That Started It All

It began with a simple request on live television.

“Minister, what is the cost per kilometer of this road?”

The question came from Arise TV anchor Rufai Oseni. The man dodging it was Dave Umahi, Minister of Works and overseer of Nigeria’s largest public-works venture—the Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway, officially priced at ₦15 trillion (≈ $11 billion).

Umahi’s response became infamous:

“You cannot talk about cost per kilometer. Every kilometer is different. Asking me that is like naming a child still in the mother’s belly.”

For a while since that exchange, Nigerians have tried to name the “child” themselves—using fragments of budget data, leaked valuations, and international benchmarks to reconstruct what the government refuses to disclose.

The Numbers on Paper

From ministry briefings and project filings, these are the only confirmed figures so far:

| Section | Route Length | Official Value | Approx. Cost / km |

| 1 Lagos | 47.47 km | ₦1.068 trillion | ≈ ₦22.5 billion |

| 2 Ogun – Ondo | ≈ 100 km | ₦1.6 trillion | ≈ ₦16 billion |

| 3A / 3B Akwa Ibom–Cross River | ≈ 130 km | ₦1.33 trillion | ≈ ₦10 billion |

| Total (to date) | ≈ 277 km | ₦4 trillion + | — |

If Section 1’s ratio holds across all 700 km, total cost would exceed ₦15 trillion, aligning with government estimates but exposing a startling unit price: ₦21–23 billion per kilometer.

At current exchange rates, that is roughly $17 million per km—triple the continental average for six-lane concrete expressways.

Benchmarking the Improbable

Independent engineers compared the Coastal Highway with similar concrete roads:

| Project | Country | Length (km) | Total Cost (USD) | USD / km |

| Nairobi Expressway | Kenya | 27 | $600 m | $22 m /km (tolled, elevated) |

| Tema Motorway Expansion | Ghana | 31 | $210 m | $6.7 m /km |

| Dakar–AIBD Toll Highway | Senegal | 32 | $220 m | $6.9 m /km |

| Lagos–Calabar (Coastal) Est. | Nigeria | 700 | $11 b (₦15 trn) | $15–17 m /km |

Only Kenya’s elevated tollway—built entirely above ground through a dense urban corridor—approaches Nigeria’s price tag. The Coastal Highway, by contrast, runs largely along undeveloped shoreline.

Analysts argue that if terrain complexity or material choice genuinely justifies construction costs that are several times higher than comparable projects, such claims should be supported by transparent data. Without publicly available cost breakdowns or engineering assessments, the rationale for the pricing remains speculative — leaving the impression of concrete without accountability.

Concrete vs. Asphalt—The Technical Excuse

Umahi’s primary defense rests on rigid-pavement construction: using reinforced concrete instead of asphalt to extend lifespan from 20 to 50 years.

Concrete is indeed costlier upfront—typically 30 to 40 percent higher—but savings accrue over time through reduced maintenance. Even so, experts say the price gap does not explain a 300 percent markup.

Engineering experts caution that the shift to concrete pavement should not translate into a blank cheque. Durability does not excuse excess; if the baseline cost is inflated, longevity merely compounds the waste. Despite repeated requests, the Ministry of Works has yet to publish the bill-of-quantities data—the detailed breakdown of materials, labor, and unit costs that would substantiate the project’s steep price escalation.

The Mystery of Section 1

Section 1, stretching from Ahmadu Bello Way (Victoria Island) to Lekki–Epe Corridor, is both the shortest and priciest.

Its 47 kilometers cut through reclaimed land, existing urban property, and sea-defense zones—factors that raise costs but not to astronomical levels.

Even assuming ₦10 billion/km for land acquisition and compensation (a generous estimate given the ₦85 billion total compensation reported for Winhomes Estate and nearby estates combined), the remaining ₦12 billion/km remains unexplained.

Section 1 of the Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway—about 47 kilometers from Ahmadu Bello Way on Victoria Island through the Lekki–Epe corridor—is both the shortest and costliest segment. Its route cuts across reclaimed land, urban property, and sea-defense zones, all legitimate cost drivers. The contract value of roughly ₦1.068 trillion implies an average cost exceeding ₦22 billion per kilometer. Even allowing generously for land acquisition and compensation costs reported around ₦85 billion in total, a large portion of the expenditure remains unexplained in publicly available documents.

An engineer within the ministry, who requested anonymity, indicated that the project’s early cost estimates incorporated wide contingency margins for wave barriers, service lanes, and future toll plazas, even though final field designs were still being developed. The budgeting process, according to internal accounts, reflected political urgency rather than engineering precision, with figures adjusted to fit timelines rather than technical validation.

Budget Silence

Ordinarily, megaprojects appear in Nigeria’s federal budget with line-item transparency. The 2025 Appropriation Act, however, lists only a lump-sum “Coastal Road Project — ₦500 billion capital allocation,” with no breakdown of sections or contractors.

When lawmakers queried the gap, the Ministry of Works replied that “contractor financing” covers the rest—a reference to the Deutsche Bank loan disclosed in Part 5 of this series. That answer moved the project off the budget books and beyond parliamentary arithmetic.

Legislative observers describe the financing model as a form of fiscal sleight of hand, where obligations are deferred and reclassified rather than openly recorded. Costs that should appear as present expenditure are instead structured to surface later as debt, allowing short-term optics of prudence while quietly expanding long-term liabilities.

The Audit Trail That Isn’t

In July 2025, the civil-society organization SERAP submitted a Freedom of Information (FOI) request to the Federal Ministry of Works, seeking disclosure of the project’s cost-per-kilometer breakdown, valuation certificates, and Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) addenda. The ministry declined, invoking national economic interest as grounds for refusal.

At the same time, the Office of the Auditor-General confirmed that it had yet to receive interim payment certificates, even though approximately ₦300 billion had already been disbursed under the heading of mobilization. Internal audit sources described the situation as an accountability vacuum—construction activity advancing rapidly while the corresponding financial documentation remains undisclosed.

Terrain and Excuses

Umahi insists topography drives cost: swampy soils, tidal surges, and sand-filling demands. To test that claim, independent surveyors analyzed geotechnical data from the Lagos coastal belt. Their conclusion: while soil stabilization adds roughly ₦2–₦3 billion per km, it still leaves ₦15 billion unaccounted for.

Even if additional seawall defenses double that figure, Section 1 remains two to three times costlier than comparable marine roads in Asia or West Africa.

“They’re using the ocean as a calculator,” quipped one project consultant. “Every wave adds another billion.”

Comparative Ghosts

Across Africa, cost transparency has become the defining test of public-sector credibility. Kenya published the entire Nairobi Expressway contract, including unit rates and financing terms. Ghana made the Tema Motorway procurement dossier publicly accessible online.

Nigeria, by contrast, remains the outlier. Neither the Bills of Engineering Measurement and Evaluation (BEME) for the Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway nor the Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP) waiver report has been released. Procurement law requires that contract details be disclosed within sixty days of award, yet nearly eighteen months later, the figures behind the nation’s most expensive highway remain shielded from public view—leaving both citizens and oversight institutions to speculate on the arithmetic of accountability.

Political Math

Inside the ministry, aides describe a culture where speed equals secrecy.

“Once the President declared it a legacy project, all timelines collapsed,” said one senior civil engineer. “No one wanted to delay the flagship by asking accounting questions.”

Umahi’s communication style reinforces that ethos. When pressed, he invokes engineering jargon—“soil reports,” “chainage variations,” “selective tendering”—turning simple arithmetic into mysticism.

For the public, the effect is alienation: citizens confronted not with figures but with faith.

The ₦15-Trillion Paradox

At ₦15 trillion, the Coastal Highway’s headline value equals nearly one-third of Nigeria’s entire 2025 budget. Yet neither Parliament nor the public can verify how that sum was derived.

Break it down:

- ₦4 trillion already contracted (Sections 1–3B).

- ₦11 trillion projected for remaining 423 km—roughly ₦26 billion per km.

- ₦747 million ($) borrowed via Deutsche Bank.

Even if future sections come cheaper, Nigeria has already locked in some of the continent’s highest infrastructure unit costs.

The Human Multiplier

Every opaque kilometer also multiplies the human cost. Compensation payments lose value to inflation, contractors inflate early margins to hedge against currency volatility, and displaced homeowners—particularly in areas such as Okun-Ajah—face chronic delays rationalized as budget adjustments.

Economists and policy observers describe a cascading effect: the absence of cost transparency inflates every link in the chain—compensation, materials, logistics, even local rent along the corridor. What begins as fiscal opacity at the top becomes, downstream, an entire micro-economy built on uncertainty and exploitation.

Comparing Concrete

Independent engineers estimate that a kilometer of six-lane concrete highway — including drainage, lighting, and signage — should cost between ₦6 billion and ₦9 billion under current Nigerian market conditions.

Allowing an additional ₦2 billion for coastal stabilization and ₦1 billion for contingencies brings the indicative total to roughly ₦12 billion per kilometer — about half the official cost declared for Section 1 of the Lagos–Calabar project.

That figure suggests Section 1 may be at least 80 percent overpriced. Whether through design inflation, procurement mark-ups, or financing charges, the arithmetic remains hidden in sealed contracts.

Why It Matters

Unit-cost transparency is more than academic. It determines:

- Budget predictability—how future sections will be funded.

- Debt exposure—how loan repayments align with deliverables.

- Accountability—whether Nigerians pay fair value for concrete.

Without it, oversight collapses. Cost secrecy turns citizens into spectators of their own indebtedness.

Voices from the Inside

A mid-level works-ministry engineer, now on leave, offered a candid explanation:

“Nobody wants to be the person who leaks the numbers. They’d lose their posting. But trust me, if the real cost per kilometer is ever published, there will be outrage.”

His estimate: ₦12 billion/km for actual works, ₦8–10 billion for everything else—‘political contingencies.’

When Silence Becomes Policy

The refusal to publish cost figures appears less an oversight than a deliberate governance tactic. By keeping numbers fluid, the ministry preserves wide discretion for renegotiation, variation orders, and new financing windows. Each design adjustment or contract amendment becomes an avenue for fiscal revision—and potential profit.

Analysts describe the Coastal Highway as a “floating project” in which the route, design, and price remain in constant motion, while only the secrecy stays fixed. The absence of stable data ensures that accountability, too, remains perpetually deferred.

The Arithmetic of Accountability

If Nigerians knew the precise cost per kilometer, they could calculate efficiency, benchmark performance, and anticipate debt service. Instead, they are told to trust engineers who will not show the math.

As one civil-society statement put it:

“We can measure the length of the highway in kilometers, but not in truth.”

Conclusion — Counting the Uncounted

The Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway was meant to symbolize precision—surveyed chainages, laser-leveled concrete, digital mapping. Yet its financials remain a blur of rounded numbers and withheld documents.

In refusing to answer the simplest question—how much per kilometer?—the Ministry of Works has turned arithmetic into state secret, and accountability into abstraction.

Until the figures are published, every kilometer poured is a line of unverified expenditure; every invoice, a new chapter of doubt. The highway grows longer each week, but so does the list of unanswered questions.

In the end, what Nigeria is really building may not just be a road across its coast, but a monument to a nation’s inability to count the cost of its own ambition.

Read also: Uzodinma Unmasked: Loot, Lies, And Imo’s Stolen Future

Part 7: Power, Paranoia and the Threat of the State

How Minister Dave Umahi turned a civil dispute into a security crusade—and what that means for free speech, justice, and investor confidence.

The Moment the Tone Changed

On air, it sounded like bravado.

“I had wanted EFCC, DSS, Police, even Interpol to come into the case,”

Minister Dave Umahi declared on Arise TV while defending the ₦15-trillion Lagos–Calabar Coastal Highway.