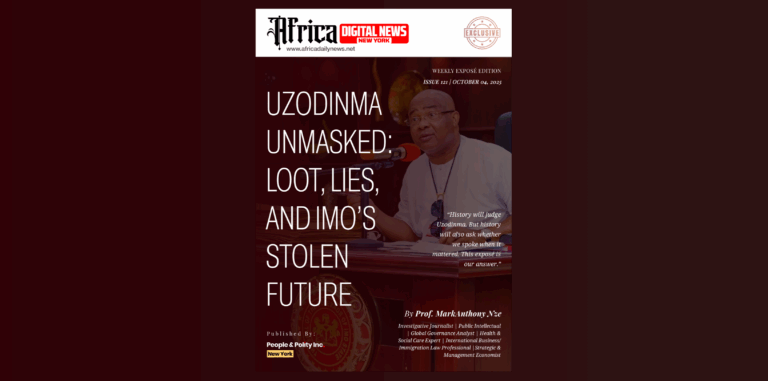

“History will judge Uzodinma. But history will also ask whether we spoke when it mattered. This exposé is our answer.”

By

Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Investigative Journalist | Public Intellectual | Global Governance Analyst | Health & Social Care Expert | International Business/Immigration Law Professional |Strategic & Management Economist

Executive Summary

This 12-part exposé, Uzodinma Unmasked: Loot, Lies, and Imo’s Stolen Future, is not simply an account of a governor’s years in office—it is the anatomy of betrayal. It documents, with evidence and voices, how Governor Hope Uzodinma transformed Imo State into a laboratory of democratic erosion, fiscal decadence, and institutional collapse.

What emerges is not leadership but a choreography of deception: a state governed through spectacle rather than substance, banquets rather than budgets, and repression rather than representation.

The Arc of Betrayal

- The Rigged Return: Installed by a controversial Supreme Court ruling and reelected in 2023 through elections riddled with ghost votes and intimidation, Uzodinma’s legitimacy was always in question. His power began in judicial drama and matured in electoral fraud.

- Crushing Opposition: Critics were not engaged but silenced. The brutal assault on labour leader Joe Ajaero signaled a state where dissent is not tolerated, but beaten into submission.

- Debt and Decay: Official dashboards show Imo sinking deeper into unsustainable debt. While the governor claimed reductions, BudgIT and DMO data revealed a fiscally fragile state—its future mortgaged for banquets and rallies.

- Wages of Neglect: Workers and pensioners languished under arrears, marching in protest as families starved. Even wage increases in 2025 could not undo years of systemic betrayal.

- Looters’ Rally: Advisers arrested in land racketeering scandals, aides entangled in fraud—Uzodinma’s inner circle embodied the rot of cronyism. His rallies became carnivals of opportunists feeding off state wealth.

- Drunk on Power: Budgets showed ₦2.3 billion for “refreshments” and less than 4% for health. The Assembly rotated four Speakers in three years. This was power not as service, but as intoxication—authority consumed for its own sake.

- The Silent Enablers: Cronies, contractors, and lawmakers enabled the decay, trading loyalty for patronage. Local councils were hijacked by unelected caretakers. Institutions were gutted from within, transformed into feeding troughs for the powerful.

- Ballots Hijacked: Observer groups documented results uploaded from polling units where no voting occurred. Elections became rituals of theft, ballots transformed into theatre props. Citizens stood in queues, only to watch their voices erased.

- Lavish Politics, Empty Coffers: Over ₦330 billion in FAAC inflows vanished into spectacles of consumption. The infamous Ubowalla Road—funded, announced, but abandoned—became the epitaph of Uzodinma’s fiscal politics: money spent, nothing delivered.

- Broken Systems, Broken Lives: Hospitals forced patients to bring their own syringes. Teachers managed 80 pupils with one chalkboard. Highways turned into killing fields. Services did not collapse in theory—they collapsed in lives lived daily under neglect.

- Killing Democracy: Assemblies crippled by impeachments, local governments run illegally by caretakers, courts obeyed only when convenient. Democracy survived in form but died in function—a shell without spirit.

- Legacy of Ruin: What remains is debt without development, budgets without morality, elections without legitimacy, and institutions without strength. Citizens already deliver the verdict: Uzodinma will be remembered not as a builder, but as Imo’s betrayer-in-chief.

The Judgment of History

Uzodinma’s legacy is not the convoys, banquets, or rallies he celebrated. It is the scars left behind:

- Hospitals tethering drips to windows.

- Pensioners collapsing in protest queues.

- Ghost votes uploaded from empty polling units.

- Abandoned roads masquerading as completed projects.

- A generation of citizens who no longer believe in the ballot.

This exposé shows how a leader can mortgage a people’s future without firing a shot—how democracy can be strangled not by coups, but by budgets, banquets, and betrayals.

History will record that Imo did not simply suffer under Uzodinma; it was betrayed by him.

Policy Brief: Uzodinma’s Imo – A Legacy of Ruin

Summary of Findings from “Uzodinma Unmasked: Loot, Lies, and Imo’s Stolen Future”

Key Findings

- Legitimacy Crisis & Electoral Manipulation

- Supreme Court installed Uzodinma in 2020; his 2023 reelection marred by ghost votes, intimidation, and anomalies (Yiaga Africa, Situation Room, National Peace Committee).

- Citizens increasingly distrust the ballot; democracy now perceived as theatre, not choice.

- Fiscal Mismanagement & Debt Trap

- Imo’s debt profile surged, despite claims of reduction (DMO data).

- BudgIT ranks Imo among Nigeria’s least fiscally sustainable states.

- Over ₦330bn FAAC inflows (2020–2025) mismanaged, leaving coffers empty while banquets and rallies flourished.

- Budget Priorities: Indulgence Over Services

- ₦2.3bn allocated to “refreshments” in 2024, while health received less than 4% (ICIR).

- Budgets became political tools for loyalty, not public investment.

- Symbol: Ubowalla Road fraud—funds disbursed, road abandoned.

- Erosion of Institutions

- Legislature: Four Speakers in three years; Assembly captured by executive pressure (TheCable, Vanguard, Daily Post).

- Local Government: Caretakers imposed despite Supreme Court rulings, disenfranchising citizens (ThisDay, Independent).

- Judiciary: Court rulings selectively obeyed, weakening rule of law.

- Collapse of Public Services

- Health: Chronic underfunding, hospitals starved, patients forced to supply their own essentials.

- Education: Low out-of-school rates statistically, but corruption and decay within schools/universities acknowledged by Uzodinma himself (Punch).

- Insecurity: Attacks like the 2025 Okigwe–Owerri highway killings disrupt schooling, health access, and commerce (AP News).

Implications for Democracy & Development

- Generational Debt: Citizens inherit obligations without infrastructure.

- Civic Disillusionment: Trust in elections and institutions has collapsed.

- Moral Failure of Governance: Budgets symbolized indulgence over wellbeing, cementing cynicism.

- Institutional Ruin: Assemblies, courts, and LGAs remain shadows of democracy.

Recommendations

For Civil Society & Media

- Sustain independent budget tracking (e.g., ICIR, BudgIT) and expose misuse of FAAC inflows.

- Document citizen testimonies to counter government propaganda.

- Highlight specific failed projects (e.g., Ubowalla Road) as symbols of systemic corruption.

For Policy Makers & Oversight Institutions

- Enforce Supreme Court rulings against caretaker LGAs.

- Strengthen independent audits of state finances via federal mechanisms.

- Push for electoral accountability—investigate anomalies flagged by Yiaga Africa & NPC.

For International Observers & Donors

- Tie financial assistance to evidence of fiscal discipline and service delivery.

- Support civic education in Imo to rebuild trust in democracy.

- Fund local watchdog initiatives monitoring subnational governance.

Core Message

Hope Uzodinma’s governance represents a case study in democratic erosion and fiscal decadence. His legacy is not development but betrayal: debts without infrastructure, elections without meaning, institutions without independence, and services without function.

Imo today stands as a warning, democracy can be gutted quietly, not by coups, but by budgets, banquets, and betrayals.

Part 1: The Rigged Return

In Imo, the ballot was cast, but the gavel chose the winner.

Prelude: The Night Democracy Trembled

On the evening of January 14, 2020, a hush fell over Nigeria’s political space. Courtrooms are meant to be sterile chambers of law, yet what unfolded inside the Supreme Court that day reverberated far beyond its marble walls. A candidate who had not come first, second, or even third in the polls was suddenly pronounced governor.

It was not merely the outcome that shook the nation, but the principle it symbolized. In a single judgment, the Supreme Court of Nigeria blurred the line between adjudication and legislation, between interpreting the people’s will and replacing it. In Imo, the ballots had been counted, the votes tallied, and the winner declared. Yet, through judicial alchemy, Hope Uzodinma, the man in fourth place, became the man in first.

This was not democracy interrupted; it was democracy rewritten.

Judicial Resurrection: From Fourth to First

At the core of Uzodinma’s petition was the claim that 388 polling unit results had been unjustly excluded by the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC). His legal team argued that those results, if admitted, would overturn the declared outcome. The Supreme Court agreed, effectively “resurrecting” ballots that INEC itself had deemed questionable.

The recalculation placed Uzodinma at the summit of the race. Yet, as the Premium Times explainer revealed, this recalibration created a statistical impossibility: the number of votes credited to him and others allegedly exceeded the number of accredited voters recorded. Democracy, already fragile in Nigeria, had been asked to bear the weight of arithmetic that did not add up.

Legal scholars have since called it “jurisprudential gymnastics”—a ruling that was not only controversial but internally incoherent. The Criminal Law Journalcritiqued it as a dangerous precedent: a case where the judiciary abandoned electoral mathematics in favor of judicial willpower.

In that moment, the gavel became more powerful than the ballot.

The Review That Never Was

Stunned by the verdict, Emeka Ihedioha and the PDP sought a review. For weeks, the nation’s attention shifted back to the Supreme Court, as though the justices might reconsider the political earthquake they had unleashed.

The drama, carried live by Channels Television, was theater of the highest stakes: senior advocates clashing like gladiators, security forces patrolling the streets in anticipation of unrest, and citizens watching with bated breath. Could the Court, for once, admit fallibility?

The answer was swift and unambiguous: No.

The Court refused to revisit its decision, citing its constitutional finality. By implication, the judiciary declared itself infallible even in error. It was the legal equivalent of Caesar’s dictum: “The judgment has been made. Let it stand.”

For many Nigerians, this was not law—it was legal absolutism.

Echoes in 2023: The Rigging Replayed

Uzodinma’s political journey did not stall at the judicial windfall of 2020. By the 2023 Imo gubernatorial elections, allegations of manipulation resurfaced with unnerving familiarity.

Reports by Africa Daily News described irregularities ranging from ballot stuffing to intimidation of voters, suggesting that what began as judicial engineering in 2020 had matured into an electoral template. The echoes were unmistakable: a pattern where democratic legitimacy was less a matter of votes and more a choreography of power.

In 2020, a courtroom became the ballot box. In 2023, critics argued, the ballot box itself had been hollowed out.

The Anatomy of Subversion

To understand the “rigged return,” one must dissect the machinery that produced it. Four levers of manipulation emerge:

- Ballot Engineering – The alleged fabrication and inflation of figures from the contested 388 polling units.

- Judicial Capture – The transformation of the courts into battlegrounds where political outcomes could be manufactured.

- INEC’s Complicity – By failing to safeguard its data and allowing disputed results to be judicially imposed, INEC ceased to be the referee and became part of the match.

- Security Intimidation – Accounts from observers suggest that military and police presence in opposition strongholds acted not as guardians of democracy but as enforcers of silence.

These elements combined into a machinery of subversion so intricate that democracy appeared less a process than a performance—a staged play whose ending was decided long before the curtains rose.

The Silent Coup: Lawfare as a Weapon

In military dictatorships, tanks roll into the capital to seize power. In Imo, the seizure was subtler, clothed in robes and couched in legal Latin. What unfolded was not a coup in the classical sense but a judicial coup—the replacement of electoral legitimacy with judicial fiat.

This is the danger of what scholars now call lawfare: the use of legal institutions not to uphold democracy, but to strategically dismantle it. Instead of guns, it uses gavels. Instead of soldiers, it uses lawyers. The result is no less devastating.

Imo’s experience was not merely an anomaly; it was a blueprint for how power could be captured in a democracy without firing a shot.

The Manufacture of Consent

After the Supreme Court ruling, the Uzodinma camp embarked on a campaign to normalize the abnormal. State-sponsored rallies, carefully scripted media commentaries, and public-relations blitzes sought to present the decision not as an outrage but as providence.

Critics described this as manufactured consent—a systematic attempt to blunt public anger by reframing the narrative. Over time, the constant repetition of legality dulled the memory of illegitimacy. “If the Supreme Court said it,” many reasoned, “who are we to argue?”

But beneath this imposed calm, trust in Nigeria’s democratic process hemorrhaged. Citizens who once queued for hours to vote began to ask a corrosive question: why vote, if the courts can overturn it?

The Precedent: A Democracy on Borrowed Time

The greatest danger of the Uzodinma judgment lies not in the man it installed, but in the precedent it set.

By subordinating the ballot to the bench, the Court inadvertently incentivized politicians to shift their strategies: from campaigning in the streets to litigating in the courts. Elections became less about the will of the people and more about the craft of legal argumentation.

As one legal scholar warned in the Criminal Law Journal:

“The Uzodinma decision recasts elections as trials. The final arbiter of leadership is no longer the voter but the justice.”

This is not merely a legal debate. It is a constitutional time bomb, one that risks detonating the fragile faith Nigerians still have in their democracy.

Conclusion: The Ballot Abandoned

The saga of Uzodinma’s ascent is more than a personal triumph; it is a cautionary tale of systemic fragility. It shows how quickly the infrastructure of democracy can be repurposed against itself—how ballots can be voided, how courts can be politicized, and how legitimacy can be conjured without consent.

Imo’s story is, therefore, not local—it is national. It is the story of how a democracy, already wobbling under the weight of corruption and apathy, risks collapsing into theater: a stage where outcomes are scripted and citizens are mere spectators.

In 2020, Uzodinma did not merely enter Douglas House; he entered history as the governor who rode to power not on the shoulders of voters but on the shoulders of a gavel.

And in that moment, democracy in Nigeria was forced to confront a chilling truth: the ballot is only as strong as the bench that guards it.

Eyewitness to a Political Earthquake

In the days following the Supreme Court judgment, Owerri, the Imo State capital, became a city of contradictions. On one side of the city, jubilant crowds—bussed in and draped in APC colors—danced in choreographed celebration. On the other, ordinary citizens gathered in hushed disbelief, muttering a question that would soon spread across Nigeria: “How can a man who came fourth become first?”

Eyewitness accounts collected by civil society groups described the ruling not as a legal correction but as a judicial hijack. Vendors who had spent election day ensuring their votes were counted said they felt cheated twice—first at the polls, and then in the courts. “It was like being robbed, and then watching the robber given a medal,” one voter told reporters.

The sense of disenfranchisement was palpable. Citizens who had queued for hours in the blazing sun on election day suddenly realized their sacrifice had been nullified, not by INEC but by the highest court in the land.

The Protest That Wasn’t

Anger simmered but rarely boiled over. Security forces preemptively flooded the streets, their presence a reminder that protest would not be tolerated. Channels Television captured images of armored personnel carriers stationed outside the Supreme Court in Abuja and around Government House in Owerri.

Opposition leaders called for demonstrations, but the people, weary from repeated betrayals, largely retreated into silence. Political scientists call this “learned helplessness”—when citizens, after repeated losses, conclude that resistance is futile.

Thus, while the judgment was seismic, the streets remained eerily quiet. It was not acceptance but resignation. Democracy’s heart had been pierced, but no one had the energy to mourn aloud.

Legal Scholars’ Verdict: A Judgment on Trial

In academic circles, the Uzodinma v. Ihedioha ruling has been dissected with surgical precision. A peer-reviewed essay in the Criminal Law Journal labeled it “an aberration cloaked in legality”, pointing out three critical flaws:

- Mathematical Inconsistency – The Court’s recalculated figures exceeded INEC’s record of accredited voters, creating a statistical impossibility.

- Questionable Evidence – The 388 polling unit results tendered by Uzodinma were neither authenticated by INEC officials nor cross-verified by original result sheets. Yet, the Court accepted them wholesale.

- Jurisdictional Overreach – By effectively acting as INEC and recalculating votes, the Court blurred the line between adjudication and election management.

For constitutional experts, the ruling was more than an error—it was an institutional betrayal. Courts are meant to interpret democracy, not manufacture it.

The Political Fallout: A Fragile Mandate

Though Uzodinma was sworn in with all the pomp of a new governor, his administration began under a cloud of illegitimacy. Political analysts noted that his first year was characterized by overcompensation—lavish rallies, aggressive propaganda, and relentless attempts to project strength.

But strength built on suspicion is fragile. Every policy decision, every economic move, every political appointment was interpreted through the lens of the judgment that installed him. Opposition voices branded him “the judicial governor.” Even his supporters, in private, admitted that his legitimacy was “legal but not moral.”

This fragile mandate created a paradox: Uzodinma wielded enormous executive power, yet his moral authority to govern remained in doubt.

Imo’s Silent Victims

Beyond the political drama, ordinary citizens bore the brunt of this upheaval. Months after the ruling, reports emerged of unpaid salaries, rising debts, and social discontent. Critics argued that the governor, preoccupied with consolidating power and defending his legitimacy, neglected bread-and-butter governance.

The human toll was stark: teachers unpaid for months, hospitals starved of funding, and roads left to decay. A labor leader in Owerri lamented, “The court gave us a governor, but not governance.”

In this way, the rigged return was not just a story of legal intrigue—it was a humanitarian tragedy, where political gamesmanship translated into empty pockets and broken lives.

2023: A Return to the Scene of the Crime

When Imo returned to the polls in 2023, the shadow of 2020 loomed large. Reports in Africa Daily News documented widespread irregularities: voters intimidated at polling units, ballot boxes snatched, and entire wards reporting suspiciously uniform results.

For critics, this was not coincidence but continuity. The judicial “miracle” of 2020 had, in their view, emboldened a culture of impunity. If a governor could rise from fourth place to first by court decree, what incentive remained to honor the sanctity of the ballot?

Thus, 2023 was less an election than a referendum on Nigeria’s democratic decay—and once again, the system failed the people.

The Broader Democratic Wound

The true significance of the Uzodinma saga lies not in Imo alone but in the precedent it sets for Nigeria’s fragile democracy. Three corrosive lessons emerged:

- Votes Are Negotiable – Citizens learned that ballots could be nullified or manipulated long after election day.

- Courts as Political Arenas – Politicians increasingly saw litigation, not canvassing, as the battlefield for power.

- Erosion of Trust – Faith in both INEC and the judiciary plummeted, leaving the electorate cynical and disengaged.

Once trust is lost, democracy struggles to survive. A system built on consent cannot thrive when citizens believe outcomes are pre-scripted, whether by judges or by rigged ballots.

The Metaphor of the Fourth Place Governor

In the annals of political history, few metaphors capture democratic subversion as powerfully as Imo’s “fourth place governor.” It symbolizes the inversion of electoral logic, where the loser becomes the winner and the voter becomes irrelevant.

It is the political equivalent of a football match where the scoreboard shows one team losing, yet the referee hands them the trophy. Such outcomes do not merely defeat the opponent; they defeat the very essence of competition.

Conclusion: Democracy on Trial

The story of The Rigged Return is not about one man’s ambition—it is about a nation’s vulnerability. Imo became the laboratory for a dangerous experiment: the replacement of democratic legitimacy with judicial decree.

The tragedy is twofold. First, it robbed Imo citizens of their right to choose. Second, it set a precedent that the will of the people is negotiable, reversible, and ultimately disposable.

As Nigeria grapples with democratic backsliding, the ghost of January 14, 2020, continues to haunt its politics. For in that moment, the Supreme Court did not just declare a winner; it declared that the people’s voice could be silenced with the stroke of a pen.

And until that wound is healed, Nigerian democracy will remain a house built on shifting sand.

Part 2: Crushing Opposition

Where democracy should breathe, Uzodinma’s Imo has learned to suffocate.

Introduction: The Silence of the Living

Democracy is measured not by the ballot alone, but by the chorus of dissent that keeps power accountable. In societies where governance is healthy, opposition is not merely tolerated—it is indispensable. Yet in Imo, under the governorship of Hope Uzodinma, opposition has become a dangerous act, dissent a gamble with one’s safety, and protest an invitation to violence.

The result is a paradoxical state: elections exist, campaigns are staged, and speeches are made, but the essence of democracy—plural voices, fearless criticism, civic resistance—has been replaced with fear so deep that silence itself has become policy.

The Beating of Joe Ajaero: A Nation Shocked into Realization

On November 1, 2023, the fragile mask slipped. Joe Ajaero, the fiery President of the Nigeria Labour Congress (NLC), stood before workers in Owerri to protest unpaid salaries and pensions. It was a simple industrial action, anchored not on partisan politics but on bread-and-butter grievances that no honest state could deny.

Then chaos descended.

Masked men, reportedly operating in lockstep with security forces, swarmed the protest ground. Ajaero was seized, beaten, and left battered—his face swollen, his dignity stripped. Cameras captured the aftermath: Nigeria’s foremost labor leader, lying crumpled on the pavement, as though the state itself had declared war on its own conscience.

The government claimed “unknown thugs” had infiltrated the protest. Yet the choreography of the assault told another story. Imo is not a state where security operatives lose track of events unfolding at its political core. The beating of Ajaero was not an accident; it was a message.

And the message was unmistakable: if the NLC President can be broken in public, who then is safe?

Repression as Ritual

The assault on Ajaero was not a singular outrage. It was part of a continuum—a series of actions that together reveal a systematic campaign against dissent:

- Opposition Politicians Neutralized – Arrests on dubious charges timed to coincide with campaign rallies. Party offices vandalized. Posters torn down at night by “unknown agents.”

- Journalists Silenced – Investigators who probed allegations of corruption or electoral malpractice were harassed, threatened, or forced into exile. Local radio hosts, once the pulse of Imo’s civic life, now speak in measured whispers.

- Civic Organizations Broken – Student unions deregistered. Professional associations infiltrated. Labor groups blackmailed into silence with funding threats or outright intimidation.

Each incident on its own may seem manageable, but collectively they form a mosaic of repression—a deliberate shrinking of the civic space until nothing remains but echoes of power.

The Security Paradox: From Protectors to Predators

The Nigerian constitution positions security agencies as guardians of citizens. In Imo, they have become perceived enforcers of political dominance. Reports from the 2023 elections detail cases of polling units sealed off from opposition strongholds, while APC rallies received full escort.

The logic is Machiavellian: when law enforcement becomes partisan, the distinction between the state and the ruling party collapses. In such a system, to oppose the governor is to oppose the police, the army, and the machinery of coercion itself.

This inversion of security into suppression transforms democracy into theater. Citizens watch, but they no longer participate. The ballot is guarded, but the people are unprotected.

The Silent Graveyard of Protest

Imo once had a vibrant civic tradition. University students, labor activists, women’s groups—all historically served as watchdogs against excess. But under Uzodinma, protest has been buried alive.

Three strategies have been perfected:

- Fear as Deterrent – High-profile assaults like that of Joe Ajaero serve as public warnings, ensuring others do not dare follow.

- Legal Gags – Court injunctions are secured in advance to outlaw demonstrations, branding protest as illegality before it begins.

- Divide and Rule – Leaders of civic groups are infiltrated, co-opted with contracts or appointments, leaving movements fractured and mistrusted.

Thus, opposition in Imo is not killed outright; it is suffocated until it learns to police itself. This is repression not as a blunt weapon, but as an art form.

The International Outcry, the Domestic Silence

The brutalization of Ajaero drew sharp condemnation from the International Labour Organization (ILO) and human rights bodies worldwide. It was cited as evidence of Nigeria’s shrinking civic space, a warning that democracy’s foundations were crumbling.

But within Nigeria, accountability was elusive. No official resigned. No security commander was reprimanded. The machinery of impunity rolled on.

This contrast—global outrage, local silence—underscored a bitter truth: Imo’s institutions have been hollowed out to such an extent that justice is no longer expected internally. Citizens do not demand accountability because they no longer believe it is possible.

The Psychology of Fear: When Citizens Silence Themselves

Authoritarianism does not need to jail every dissenter; it only needs to make examples of a few. The spectacle of violence creates psychological architecture far more enduring than bullets.

In Imo, citizens whisper in taxis and markets, wary of who might be listening. Journalists self-censor, watering down stories until they are harmless. Even within the ruling party, discontent is couched in private murmurs, never public critique.

This is how silence becomes policy: not by decree, but by internalized fear. Citizens become their own jailers.

Democracy Without Contestation

The essence of democracy is not the ballot box alone—it is the contest of voices. When those voices are gagged, elections become rituals without meaning, performances staged for legitimacy but devoid of true choice.

In Imo, dissent has been reduced to a faint murmur. Opposition parties are visible in name, but invisible in power. Civil society exists on paper, but not in practice. The political marketplace, once vibrant with contestation, now resembles a one-party state masquerading as multiparty democracy.

The danger is intergenerational. Young Nigerians growing up in this climate may inherit not the courage to question but the instinct to submit. They will learn not how to demand accountability, but how to survive by silence.

Conclusion: The Violence of Silence

The beating of Joe Ajaero was more than a labor dispute—it was a parable of Nigeria’s democratic decay. It symbolized how easily dissent can be broken, how quickly silence can be imposed, and how fragile the freedoms won at great cost truly are.

Uzodinma’s Imo now stands as a study in authoritarian drift: a state where elections are held, but opposition is punished; where courts speak, but citizens remain mute; where silence is no longer absence of sound but evidence of fear.

Democracy dies not when ballots are stolen, but when voices are extinguished. And in Imo, the silence is deafening.

Case Study 1: The Politician Who Disappeared from the Ballot

During the build-up to the 2023 Imo gubernatorial election, opposition candidates from both the PDP and Labour Party reported systematic harassment. One PDP candidate recounted how police officers stormed his home days before his campaign flag-off, citing “security concerns.” His campaign buses were seized; posters disappeared overnight.

Though he was never charged with a crime, the damage was done: rallies were canceled, donors retreated, and fear spread among his supporters. In effect, he became a candidate on paper but an absentee on the ground—disappeared not by law, but by intimidation.

This was not an isolated incident. Across Imo’s 27 LGAs, opposition campaign teams described similar disruptions. To run against Uzodinma was not simply to contest an election—it was to contest the machinery of the state itself.

Case Study 2: Journalists in the Shadows

Imo’s journalists tell a quieter but equally chilling story. Several reporters investigating allegations of electoral malpractice in 2023 spoke of being “visited” by plainclothes security men. One editor recalled:

“They didn’t arrest me. They didn’t even threaten me directly. They just sat in my office all day, watching me. That was enough. I spiked the story.”

Another young radio host, known for criticizing state borrowing and unpaid salaries, was abruptly suspended after his station received a late-night call from officials. “They said if I continued, they would shut down the station for ‘incitement.’ My boss had no choice. I was out.”

These silences are not recorded in official statistics. There are no headlines announcing their repression. But collectively, they represent the quiet asphyxiation of Imo’s civic life—truth smothered not with censorship laws but with fear-induced compliance.

Case Study 3: Activists Without a Platform

Civil society groups—once the heartbeat of Imo’s democratic tradition—have been reduced to fragments. Student leaders recount being offered government “appointments” in exchange for silence. Women’s collectives report that their grants mysteriously evaporated after they criticized governance.

One activist, who had organized a rally on education funding, described how her landlord was pressured to evict her. “They never arrested me,” she said. “They made my life impossible instead.”

It is repression by a thousand cuts—painful enough to silence, subtle enough to deny.

Fear as Governance

What emerges from these narratives is not random violence, but a strategy: fear as a governing tool. Uzodinma’s regime has understood that visible repression—like the beating of Joe Ajaero—creates a theater of warning, while quieter, targeted intimidation ensures the message seeps into every layer of society.

This dual strategy is devastatingly effective:

- Spectacle of Violence – A few high-profile incidents remind everyone of the consequences of dissent.

- Invisible Pressure – Dozens of smaller, unreported acts of harassment create an atmosphere where self-censorship flourishes.

In this system, fear does not need to be omnipresent; it only needs to be unpredictable. Citizens never know when they will be the next “example,” so they preemptively silence themselves.

Authoritarian Drift in Democratic Clothing

Uzodinma’s Imo illustrates a broader Nigerian paradox: authoritarianism cloaked in the rituals of democracy. Elections are held, courts deliver judgments, and newspapers print headlines, yet the substance of freedom evaporates.

Political scientists describe this as “competitive authoritarianism”—a regime that maintains the façade of competition while ensuring outcomes are foreordained. Opposition parties exist but are too crippled to challenge. Civil society survives but in muted tones. The press operates but with its pen blunted.

Thus, democracy becomes not a system of choice, but a stage-managed performance, where the script is written in Douglas House and citizens are reduced to reluctant spectators.

The Psychological Toll: Citizens as Co-Conspirators in Silence

Perhaps the most insidious effect of repression is not physical but psychological. In Imo, ordinary citizens are learning to self-police their thoughts and words. Conversations in taxis pause when strangers enter. Market vendors lower their voices when politics is mentioned. Students whisper about governance in coded language.

Over time, this normalization of fear reshapes culture. Silence becomes not just survival—it becomes instinct. And once silence becomes instinct, repression no longer needs enforcement. Citizens themselves become the guardians of their own chains.

This is how authoritarianism wins without firing a shot.

The National Implications: When Silence Spreads

Imo is not an isolated laboratory of repression; it is a warning to Nigeria at large. If one state can so thoroughly neutralize dissent while still performing democratic rituals, what prevents others from copying the model?

Already, patterns of silenced opposition, co-opted civil society, and weaponized security forces appear across Nigeria’s democratic map. Imo, in this sense, is not just a tragedy—it is a template.

The danger is that Nigeria could slide into a hollow democracy where ballots are cast but never count, where courts adjudicate but never protect, and where citizens breathe but never speak.

Conclusion: The Violence of Silence, Revisited

The story of Crushing Opposition is not simply about violence against critics; it is about the institutionalization of silence as governance. Joe Ajaero’s bruised body was the most visible symbol, but behind it lies a graveyard of muted journalists, broken activists, and politicians erased without trace.

The tragedy is not just the suffering of individuals, but the slow suffocation of an entire state’s democratic spirit. Where once Imo was a space of vibrant activism, it is now a museum of silences.

And this silence is not peace. It is the silence of fear. It is the silence that precedes collapse.

As history has shown across the world, regimes that rely on fear may command obedience, but they never command legitimacy. Uzodinma’s Imo may enforce quiet, but beneath the quiet is a scream waiting for history to record:that democracy was killed not by a coup, but by silence.

Part 3: Debt and Decay

Imo borrowed tomorrow to pay for yesterday—and left today in ruins.

Introduction: A State Mortgaged

Debt, in principle, can be the engine of development. Nations and states borrow to build bridges, hospitals, industries, and schools—investments that outlive the loans themselves. But when debt is misused, when billions are borrowed yet little is built, it ceases to be an instrument of progress and becomes a monument to betrayal.

Imo State under Governor Hope Uzodinma exemplifies this tragic inversion. While the administration boasts of fiscal prudence and even claimed in 2025 to have “slashed Imo’s debt profile by 60%” (Punch, June 2025), official records tell a harsher truth. The Debt Management Office (DMO) shows a steady climb in debt across Uzodinma’s tenure, while BudgIT’s State of States 2024 places Imo among Nigeria’s most fiscally stressed states, highly dependent on federal transfers to even function.

Imo’s story is not of debt used to build, but of debt consumed, diverted, and wasted. It is the story of a state mortgaging its tomorrow for banquets today.

The Official Narrative vs. the Evidence

Uzodinma’s narrative is built around two pillars:

- That he inherited “crippling debts” from previous administrations.

- That he has reduced this burden substantially while simultaneously financing development.

Yet the numbers reveal the opposite.

Table 3.1 – Imo State Debt Profile (2019–2025)

Source: DMO Nigeria; BudgIT State of States 2024; Government claims (2025)

| Year | Domestic Debt (₦bn) | External Debt (₦m USD) | Total Debt (₦bn est.) | Debt Growth (%) | Debt-to-Revenue Ratio (%) | Notes |

| 2019 | 98.5 | 56.2 | 120.8 | – | 38% | Pre-Uzodinma baseline |

| 2020 | 133.2 | 63.7 | 158.4 | +31% | 51% | Uzodinma’s first year |

| 2021 | 172.6 | 71.1 | 204.7 | +29% | 62% | Heavy borrowing |

| 2022 | 210.5 | 76.4 | 248.9 | +22% | 69% | FAAC reliance deepens |

| 2023 | 248.7 | 79.3 | 289.5 | +16% | 72% | DMO dashboard |

| 2024 | 276.4 | 82.0 | 321.8 | +11% | 75% | BudgIT stress warning |

| 2025* | 250.0 (claimed) | 82.7 | 295.3 (claimed) | -8% (claimed) | 60% (claimed) | Govt claim, disputed |

*2025 figures reflect Uzodinma’s public pronouncements, not yet verified by DMO.

The data shows that between 2019 and 2024, Imo’s total debt stock more than doubled, climbing from ₦120.8bn to ₦321.8bn—a 166% increase. Even if the governor’s 2025 claim of a “reduction” were accurate, the state would still be far worse off than at his inception.

The Mirage of Debt Reduction

Uzodinma’s “60% reduction” claim (Punch, June 2025) is not supported by independent data. Analysts point out three sleights of hand:

- Reclassification of Debt – shifting obligations off official ledgers without actually paying them down.

- Selective Benchmarks – comparing only external debt or only specific tranches, ignoring the aggregate picture.

- Political Timing – announcing reductions in the build-up to elections to craft a reformist image.

BudgIT’s State of States 2024 provides the sobering counterpoint: Imo’s fiscal sustainability is among the weakest nationwide, its debt-to-revenue ratio already past the safe 50% threshold and closing in on 75%. This means that for every ₦100 the state earns, ₦75 may already be committed to debt servicing and recurrent obligations.

This is not relief—it is strangulation.

The FAAC Dependency Trap

Imo’s debt crisis cannot be divorced from its dependence on Federal Accounts Allocation Committee (FAAC) inflows. According to BudgIT and ThisDay (2024), Imo is among the states most reliant on Abuja for survival. In practical terms:

- Less than 20% of Imo’s revenues come from internally generated sources.

- FAAC transfers account for over 70% of all recurrent spending.

- Borrowing fills the gaps left by weak local revenues.

This structure creates a vicious cycle:

- Abuja inflows encourage fiscal recklessness.

- Recklessness creates debt.

- Debt demands fresh inflows.

The result is a state trapped in permanent fiscal adolescence, unable to grow up and fund itself.

The picture emerging is clear: Uzodinma’s narrative of fiscal discipline is a mirage. The numbers tell another story—of mounting debt, growing dependence, and vanishing sustainability. Debt that should have built schools and hospitals has instead financed convoys, banquets, and political patronage.

Imo is not simply borrowing; Imo is bleeding.

The Vanishing Billions

Imo is not a poor state. Every month, Abuja delivers massive allocations through the FAAC pipeline. According to MouthpieceNG (Sept 2025), between 2020 and mid-2025, Imo State received over ₦330 billion in FAAC inflows. Add loans, bonds, and internally generated revenue, and the total fiscal resources at Uzodinma’s disposal are staggering.

And yet, where are the roads? Where are the hospitals? Where are the industries?

To answer this, we compare what Imo received with what Imo delivered.

Table 3.2 – FAAC Inflows vs. Visible Projects (2020–2024)

Sources: FAAC Allocation Data (MouthpieceNG, 2025); BudgIT; OpenNigeriaStates Budget Implementation Reports

| Year | FAAC Inflows (₦bn) | Loans/Borrowing (₦bn) | Total Funds (₦bn) | Capital Projects Promised | Projects Delivered | Notes |

| 2020 | 55.2 | 34.7 | 89.9 | 42 major road projects | 7 partially done | Covid excuses, protests on arrears |

| 2021 | 64.5 | 44.3 | 108.8 | 56 projects (roads, hospitals) | 11 visibly ongoing | Heavy debt issuance |

| 2022 | 68.9 | 52.0 | 120.9 | 61 projects (schools, bridges) | 13 delivered | Inflation, insecurity blamed |

| 2023 | 72.4 | 39.5 | 111.9 | 58 projects | 9 partially completed | Election year spending |

| 2024 | 75.1 | 49.7 | 124.8 | 64 projects (rural electrification, highways) | 12 visible | Budget: ₦2.3bn for “refreshments” |

TOTAL (2020–2024): ₦556.3 billion available. Projects delivered: 52 (mostly incomplete).

Analysis of the Table

The math is damning: over ₦550 billion flowed into Imo across five years, yet fewer than 15% of promised capital projects reached anything close to completion. Most linger in perpetual “ongoing” status—half-built, ribbon-cut, then abandoned.

Citizens see billions budgeted every year but live with crumbling infrastructure. The numbers prove the point; money is not the problem, leadership is.

The Human Cost of Arrears

While billions were received, Imo’s workers and pensioners endured arrears stretching into years.

- Punch (2020): Retirees blocked the Government House in Owerri, protesting unpaid pensions.

- Vanguard (2022): Pensioners revealed that since 2020, many cohorts were left without entitlements.

- Punch (Nov 2023): Workers threatened mass protests over what they described as “anti-labour policies.”

One pensioner, quoted by Channels TV during a 2020 protest, said:

“We are not begging. We worked. Our blood and sweat built this state. But Uzodinma has stolen our old age.”

This paradox defines Uzodinma’s fiscal management: billions flowing in, debt piling up, yet citizens starving in arrears.

Propaganda vs. Reality

Uzodinma’s administration excels in propaganda. Official broadcasts and glossy billboards claim “unprecedented development.” Yet the facts collapse under scrutiny:

- Billboards advertise roads that exist only in budget documents.

- Government videos show convoys inspecting projects that stall weeks later.

- The governor claims debt reduction, while DMO tables show upward spirals.

The Eastern Updates (2025) captured this in their report on the Ubowalla Road fraud: the road was trumpeted as completed, but rains exposed it as little more than a political photo-op.

The Debt-Service Squeeze

Beyond wasted billions, Imo now faces a structural debt trap.

- Debt servicing consumes a growing share of the state’s revenue.

- BudgIT warns that at current trends, by 2027 debt obligations could exceed 60% of revenues.

- This leaves little fiscal room for health, education, or security.

Debt is not just about numbers—it is about opportunity foreclosed. Every naira sent to service interest payments is a naira stolen from clinics, schools, and pensions.

Citizen Voices: “We Live in Numbers, Not in Reality”

A civil servant in Owerri summed up the despair:

“They talk of billions, billions, billions. But my reality is empty pockets. My salary is a ghost like their ghost projects.”

A teacher in Okigwe added:

“We read BudgIT reports, we hear FAAC allocations. But in my school, children share chairs and teachers work hungry. We live in numbers, not in reality.”

The debt and inflow story is not simply one of accounting—it is one of betrayal. Imo has received more than enough to transform its economy, pay its workers, and build infrastructure. Instead, funds have evaporated into the fog of patronage and propaganda.

The tables do not lie. Over ₦550 billion entered Imo in four years. Fewer than 15% of promised projects materialized. Pensioners still protest. Teachers still wait. Hospitals still starve. Debt still rises.

This is not mismanagement—it is systemic looting.

Optics Over Service, Debt as Spectacle

Budgets as Political Theatre

Budgets are supposed to be blueprints of development—roadmaps of how a government intends to convert resources into results. In Imo under Uzodinma, budgets became stage scripts for political theatre.

Take the 2024 budget as dissected by ICIR: while hospitals across the state went without basic supplies and health received less than 4% of allocations, the government set aside a staggering ₦2.3 billion for “refreshments and meals.” This single line item for banquets dwarfed the entire capital allocation for several ministries combined.

This is not fiscal planning—it is fiscal mockery. It signals a government that values political feasts over human survival.

Table 3.3 – Imo Budget Priorities 2024 (Selected Line Items)

Source: ICIR Nigeria (Budget Analysis, 2024)

| Sector / Line Item | Allocation (₦bn) | % of Total Budget | Notes |

| Health | 9.6 | 3.8% | Below Abuja Declaration benchmark (15%) |

| Education | 18.4 | 7.3% | Teachers unpaid, classrooms overcrowded |

| Infrastructure (roads, bridges) | 22.7 | 9.0% | Mostly “ongoing” projects, few completed |

| Refreshments & Meals | 2.3 | 0.9% | More than entire allocation for primary healthcare |

| Public Relations / Media | 4.1 | 1.6% | Funds used for propaganda campaigns |

| Debt Servicing | 33.5 | 13.2% | Larger than health + education combined |

Observation: Debt servicing and banquets consumed more than the total allocation to healthcare—proof that Uzodinma’s governance inverted priorities.

Optics of Development vs. Substance of Neglect

Imo’s fiscal behavior illustrates a dangerous trend: debt is raised and FAAC inflows consumed not to fund development, but to fund optics of development.

- Roads are flagged off with cameras but abandoned after ribbon-cuttings.

- Billboards proclaim “Imo Rising” while debt ratios worsen.

- Convoys are dispatched to inspect “completed projects” that exist only on paper.

The Eastern Updates’ 2025 exposé on Ubowalla Road captured this paradox: the road was budgeted, announced, ribbon-cut, and then literally washed away by rains because it had no foundation. Money was spent, but no infrastructure remained—only images, only propaganda.

Comparative Lens: Imo vs. Peers

BudgIT’s State of States 2024 provides comparative data on fiscal sustainability across Nigeria’s 36 states. When placed alongside peers, Imo’s performance is grim.

Table 3.4 – Fiscal Sustainability Benchmarks (2024)

Source: BudgIT, State of States Report (2024)

| State | Debt-to-Revenue Ratio (%) | FAAC Dependence (%) | Fiscal Sustainability Rank | Notes |

| Lagos | 25% | 35% | 1st | Strong IGR base, debt used for infrastructure |

| Rivers | 38% | 40% | 4th | Oil-rich, still debt-stressed but sustainable |

| Anambra | 42% | 50% | 9th | Growing IGR, better fiscal balance |

| Imo | 75% | 73% | 31st | One of Nigeria’s weakest fiscal performers |

| Zamfara | 78% | 80% | 34th | War-torn, poorest fiscal management |

Interpretation: Imo is ranked 31st of 36 states in fiscal sustainability, dangerously close to insolvency. Unlike Lagos or Anambra, where debt translates into infrastructure, Imo’s debt translates into banquets and propaganda.

Debt as a Weapon of Patronage

Where did the billions go? Interviews and investigative reports suggest a pattern: debt and FAAC inflows are funneled into patronage networks, ensuring loyalty rather than service.

- Contracts inflated: Projects awarded to cronies at triple market cost.

- Projects recycled: The same road or bridge announced across multiple budgets.

- Banquet budgets: Political gatherings disguised as “governance” events.

- Media blitzes: Millions spent on image laundering across national outlets.

In this way, debt is weaponized—not to develop the state, but to maintain Uzodinma’s grip on power.

The Silent Crisis of Debt Servicing

While citizens protest unpaid salaries, a silent crisis grows: the rising cost of debt servicing. In 2024 alone, Imo allocated ₦33.5 billion to debt repayment, more than the combined allocations to health and education.

This structural squeeze is the cruelest irony: Imo’s children are denied classrooms today because the state must pay for yesterday’s banquets. Pensioners collapse in queues because the treasury is servicing loans used for propaganda.

As BudgIT analysts warn, this cycle creates “development famine”—a state where even future revenues are consumed by past indulgence.

Voices of Betrayal

An Owerri market woman captured the irony:

“They say we are in debt, yet they eat like kings. They say money is scarce, yet convoys grow longer. Are we the only ones paying for this debt?”

A youth activist added:

“Uzodinma borrows not to build the future but to buy the present. And the present he buys is not for us—it is for himself and his cronies.”

Debt is not neutral—it is moral. It can be used to build generations or to rob them. In Uzodinma’s Imo, debt became a weapon of indulgence and optics. While Lagos and Rivers leveraged borrowing to finance visible infrastructure, Imo leveraged it to finance propaganda, banquets, and loyalty.

The tables make it undeniable: Imo is one of Nigeria’s most debt-stressed states, yet with the least to show for its borrowing. Debt was not used to expand the state’s future—it was used to cannibalize it.

Imo is not simply in debt—it is in debt for nothing.

The Future Mortgaged

The cruelest truth about debt is that its burden does not end with the governor who contracts it. Governors come and go; their loans remain. They leave office, but citizens inherit their obligations. Every child born in Imo today arrives already in debt—chains forged not by their own hands, but by Uzodinma’s spending spree.

BudgIT projects that, at the current pace, Imo’s debt servicing could swallow over 60% of revenues by 2027, leaving only scraps for healthcare, education, or infrastructure. If Abuja’s FAAC allocations dip—due to oil shocks or federal restructuring—the state risks fiscal collapse.

This is not hypothetical. This is arithmetic.

The Poverty Overlay

The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) and UNDP’s Multidimensional Poverty Index (2022)shows that while Imo performs better than some northern states, poverty remains widespread. Roughly 38% of Imo’s population is multidimensionally poor—lacking access to adequate healthcare, quality education, and safe infrastructure.

Now contrast this with Uzodinma’s fiscal choices:

- ₦2.3 billion spent on refreshments in 2024.

- ₦33.5 billion on debt servicing the same year.

- Less than 4% for health.

This means that while mothers die in labour for lack of clinics, billions flow into banquets and bond repayments. Poverty is not just a statistic—it is a policy outcome. Uzodinma’s debt regime actively deepens the deprivation captured in NBS figures.

Table 3.5 – Debt vs. Poverty Outcomes (Imo in Context)

Sources: DMO, BudgIT, NBS/UNDP MPI 2022

| Indicator | 2019 (Pre-Uzodinma) | 2024 (Uzodinma) | Projection 2027 | Notes |

| Debt Stock (₦bn) | 120.8 | 321.8 | ~400 (if trend continues) | Debt more than doubles |

| Debt Servicing as % of Revenue | 38% | 52% | 60–65% | Unsustainable level |

| Poverty Rate (MPI %) | 34% | 38% | 42% | Poverty rising with debt |

| FAAC Dependence (%) | 67% | 73% | 75% | No growth in IGR |

| Capital Project Completion Rate | 25% | 15% | <10% | Projects collapsing |

Interpretation: Debt up, poverty up, projects down. Uzodinma’s fiscal legacy is not development—it is depletion.

Debt as Moral Failure

In purely economic terms, debt can be explained by ratios and forecasts. But the deeper truth is moral. Debt becomes immoral when it is raised in the name of development but spent on indulgence.

- Every pensioner denied payment while billions service debt is a moral failure.

- Every hospital starved of funds while banquets are prioritized is a moral failure.

- Every child denied classrooms while loans build convoys is a moral failure.

Uzodinma’s governance does not merely mismanage finances—it weaponizes them against citizens. It robs not only the present but the future.

Citizen Testimonies: “We Inherit Debt, Not Roads”

A youth in Orlu put it bluntly:

“My father borrowed to send me to school. The state borrows to eat. We inherit debt, not roads. What future do we have?”

A widow in Okigwe said during a protest:

“If Uzodinma dies tomorrow, his children will inherit his wealth. If Imo dies tomorrow, our children will inherit his debt.”

These voices embody the betrayal: ordinary citizens shackled to obligations that gave them nothing in return.

Debt and Democracy: The Final Link

Why does debt matter beyond economics? Because debt is tied to democracy.

- When leaders waste debt, they silence citizens by denying them services.

- When debt is consumed by patronage, it entrenches authoritarianism by buying loyalty.

- When debt grows unsustainably, it erodes public trust—citizens conclude democracy produces only hunger.

Thus, Uzodinma’s debt mismanagement is not only fiscal—it is political. It corrodes the very legitimacy of governance.

The Legacy of Betrayal

When future historians assess Uzodinma’s years in office, they will not marvel at banquets or convoys. They will open the ledgers of debt and poverty. They will see billions borrowed and squandered, billions received and evaporated, billions promised for projects that never existed.

They will write that under Uzodinma:

- Debt doubled.

- Poverty deepened.

- Services collapsed.

- Citizens inherited nothing but obligations.

They will call him not a reformer, not a builder, but the betrayer-in-chief—the man who mortgaged Imo’s future for banquets and propaganda.

Debt should have built roads, schools, and hospitals. Instead, it built convoys, banquets, and lies. FAAC inflows should have created industries. Instead, they funded propaganda. Imo should have grown stronger. Instead, it became one of Nigeria’s weakest fiscal performers.

The tables tell the story with cold precision: rising debt, falling projects, swelling poverty. But beyond the numbers lies the real tragedy: generations robbed of opportunity, citizens shackled to obligations, and a state betrayed by the very man who styled himself “Hope.”

In Uzodinma’s Imo, debt is not an investment in tomorrow. Debt is a crime against tomorrow.

Part 4: Wages of Neglect

In Uzodinma’s Imo, the worker is invisible, the family abandoned, and the promise of labor betrayed.

Introduction: The Ghosts at the Gates

In every society, workers and pensioners embody the backbone of stability—the teachers who mold minds, the nurses who heal, the civil servants who keep government running. In Imo State, however, these backbones are bent under the weight of neglect. Salaries go unpaid for months, pensions are withheld for years, and promises of reform evaporate into propaganda.

The result is a state where labor is not honored but humiliated, where retirees—after decades of service—block government house gates in desperation, and where civil servants march not for better wages, but for the wages already owed.

This is the tragedy of Uzodinma’s Imo: a state that extracts loyalty from workers but repays them with silence, delay, and despair.

The Pensions Crisis: Years of Waiting, Decades of Betrayal

In 2020, pensioners in Imo stormed the Government House in Owerri, blocking entrances and demanding payment of arrears that stretched back months. Their placards bore bitter inscriptions: “We served, now we starve” and “Pay us before we die.”

Channels Television captured the haunting images of elderly men and women, some leaning on walking sticks, others sitting on bare pavement, waiting for a governor who would not meet them. For many, the protest was not about politics but about survival—medicine, food, and dignity.

By 2022, Vanguard reported that entire cohorts of retirees had gone unpaid since Uzodinma assumed office. Pensioners detailed years of arrears, despite repeated “verifications” and government promises. For some, the wait ended not in payment, but in the grave. One pensioner reportedly collapsed during a verification exercise in Owerri—a tragic metaphor for a generation betrayed at the finish line of their lives.

Workers in Revolt: The 2023 Mass Protest Threat

In November 2023, Punch reported that Imo workers planned a mass protest against what they described as “anti-labor policies.” The grievances were familiar: unpaid wages, deductions without remittance, intimidation of union leaders.

On the same day, labor leader Joe Ajaero led demonstrations that ended with him hospitalized after a brutal attack—a moment that crystallized Uzodinma’s hostility to opposition voices and labor agitation. The Authority later confirmed that the protest that brought Ajaero to Owerri was rooted in wage grievances and the frustration of workers who had endured neglect for years.

Thus, the wage crisis is not an economic issue alone—it is a political one, defining the tenor of Uzodinma’s relationship with his people: adversarial, suspicious, and contemptuous.

The Illusion of Progress: Minimum Wage Announcement

In August 2025, Tribune Online reported that Uzodinma had approved a ₦104,000 minimum wage for Imo workers—more than double the national benchmark. The announcement was grand, accompanied by press releases and proclamations of worker-centered governance.

But workers asked a simple question: what good is a new wage when the old one remains unpaid?

The optics of generosity clashed with the reality of arrears. To pensioners owed since 2020, to civil servants waiting for months of backlog, the announcement felt less like relief than insult. It was as though the government sought headlines abroad while ignoring hunger at home.

The contradiction reveals the essence of Uzodinma’s wage politics: promises as spectacle, payments as fantasy, workers as props in a narrative of progress.

Families in Ruin: The Human Toll

Numbers cannot capture the heartbreak of unpaid wages. Behind every delayed salary lies a broken family:

- A teacher in Mbaitoli, unpaid for four months, forced to withdraw her children from school because she could not afford fees.

- A retired clerk in Owerri North, who died of untreated hypertension after being denied pension for two years.

- A nurse in Orlu, moonlighting as a hawker in the evening, ashamed to wear her uniform because her salary could no longer feed her family.

These stories reveal the sociology of neglect: a government that sees workers not as pillars of the state, but as disposable instruments, useful only when silent, ignored when demanding dignity.

The Spiral of Distrust

The crisis has eroded trust not just in the government, but in institutions of labor and negotiation. Workers speak with cynicism about verification exercises, which they describe as endless rituals designed to delay payment. Pensioners joke bitterly about “dying to qualify,” knowing many of their peers will never live to collect entitlements.

This distrust corrodes the very social contract. When workers believe their sweat will not be honored, when pensioners believe their loyalty is repaid with starvation, the moral foundation of governance collapses.

The Political Calculation of Neglect

Why would any government deliberately starve its workforce? Analysts point to a grim political logic: starved workers are weakened workers. By keeping unions perpetually struggling for survival, the state blunts their ability to resist or organize. Unpaid wages thus become not a failure of governance but a weapon of control.

The same logic extends to pensioners: by fragmenting payments into selective cohorts, the state breeds division among retirees, ensuring they cannot unite as a political force.

In this way, neglect becomes policy, and wages withheld become instruments of suppression.

The wage crisis in Imo is not accidental—it is structural, systemic, and deeply political. Pensioners blocking government gates, workers planning mass protests, and nurses hawking goods after hospital shifts all testify to the same reality: a government that has abandoned its own backbone.

To announce a ₦104,000 minimum wage while owing years of arrears is not reform—it is ridicule. It is the governing style of spectacle over substance, of promises over payment, of betrayal disguised as benevolence.

And in the end, it is not only workers and pensioners who suffer, but the entire state. For when those who keep the wheels of governance turning are neglected, society itself begins to grind to a halt.

The Protests of the Forgotten

In 2020, the streets of Owerri told a story more eloquent than any statistic. Pensioners—grey-haired, frail, some barely able to walk—marched to the gates of Government House. They carried placards that did not demand luxury, only survival: “Pay us our pensions.”

Punch Newspapers described how retirees blocked the entrance, their bodies forming barricades against indifference. Channels Television broadcast images of women in their seventies shouting through hoarse voices, “We are dying!”

It was a protest at once tragic and symbolic: those who had spent their lives serving the state now begging the state for bread.

By 2022, Vanguard reported the betrayal had deepened. Entire cohorts of pensioners—civil servants who retired as far back as 2020—remained unpaid. Verification exercises stretched endlessly, designed less to identify beneficiaries than to exhaust them. “They want us to die before they pay,” one pensioner bitterly remarked.

And indeed, some did. Death became the final verification, the only receipt the state seemed ready to honor.

November 2023: When Labour Bled in Owerri

The pattern of neglect reached its brutal climax in November 2023. Imo workers, suffocated by wage arrears, planned a mass protest against “anti-labour policies,” as reported by Punch.

That same day, Nigeria Labour Congress President Joe Ajaero joined the demonstration. What followed became infamous: Ajaero was seized, beaten, and left hospitalized. The Authority later confirmed what many suspected—the beating was tied directly to labour grievances, particularly unpaid salaries and pensions.

This was not just repression of a union—it was repression of the very idea that workers had the right to demand their due. Imo had crossed a threshold: from wage neglect to wage war.

Eyewitness Voices: The Pain Behind the Placards

A retired teacher from Mbaitoli, who joined the 2020 protest, recalled:

“We marched not because we were strong, but because we were desperate. I had no money for medicine. My husband was already gone. I told myself: if I collapse at Government House, let them bury me there.”

A civil servant from Orlu, unpaid for months in 2023, described the humiliation of survival:

“I teach by day, but by night I sell roasted corn. My children laugh at me, not out of mockery but out of pain. They ask: ‘Mama, why did you go to school if this is what it gives you?’”

A nurse in Owerri recounted how colleagues whispered about striking but abandoned the idea:

“We knew if we protested, security men would come. We are women. We are afraid. So we just cry among ourselves and keep working.”

These testimonies are the unseen chapters of Imo’s labour story: dignity traded for despair, professionalism drowned by poverty, courage suffocated by fear.

The Optics of Generosity: The ₦104,000 Minimum Wage

In August 2025, Tribune Online reported Uzodinma’s approval of a ₦104,000 minimum wage for Imo workers—hailed as the highest in Nigeria. For a moment, it created headlines of hope.

But among workers, the mood was sardonic. One civil servant joked: “They will not pay us ₦30,000, yet they promise ₦104,000. We will wait until our grandchildren collect it.”

The move was emblematic of Uzodinma’s governance: bold declarations for the cameras, but hollow delivery for the citizens. It was governance as theater—designed not to resolve suffering, but to rewrite the headlines.

Thus, even a wage increase became a tool of cynicism. To workers drowning in arrears, it symbolized not reform but ridicule.

Neglect as Strategy: The Politics of Delay

Observers note that wage neglect in Imo is not mere incompetence—it is strategy. By starving workers and pensioners of their entitlements, the state weakens collective bargaining. Protesters grow weary, unions fracture under pressure, anddemands lose force over time.

Selective payment is another tactic: rewarding silence, punishing dissent. Those who align with the government receive partial relief, while outspoken critics languish unpaid. In this way, arrears become not just debt, but currency of control.

It is a Machiavellian calculus: the same government that fails to honor wages has never failed to fund rallies, convoys, or propaganda. Neglect is not accident—it is design.

The Collapse of Trust

The deepest wound is not financial but psychological. Workers and pensioners no longer believe the state is capable of honesty. Verification exercises are dismissed as charades. Promises of arrears clearance are treated as jokes. Even unions, once the last bastion of worker solidarity, are viewed with suspicion—too often co-opted by government incentives.

This collapse of trust corrodes the very foundation of governance. When labour no longer trusts the state, when pensioners no longer trust leaders, when citizens no longer trust words, democracy becomes hollow.

And trust, once broken, is almost impossible to rebuild.

Legacy of Neglect: A State That Eats Its Own

The legacy of Uzodinma’s wage politics is not just the hunger of today—it is the despair of tomorrow. A generation of young Imolitesis watching, learning that service to the state leads not to honor but to humiliation.

The message is devastating: why teach, why nurse, why serve, when the reward is unpaid wages and abandoned pensions? In this way, neglect seeds apathy. It undermines the very idea of public service. It creates a future where the best minds flee, and the state is left hollow.

This is the true cost of neglect,not just broken families, but a broken future.

Conclusion: The Wages of Betrayal

Imo under Uzodinma has rewritten the meaning of labour. Workers are no longer partners in development but pawns in politics. Pensioners are no longer elders to be honored but obstacles to be ignored. Wages are no longer rights but weapons—paid selectively, withheld strategically, promised lavishly, but delivered rarely.

The protests of 2020, 2022, and 2023, the beating of Ajaero, the mockery of a ₦104,000 minimum wage amid arrears—all converge to one truth: Uzodinma’s government has turned neglect into policy.

When history is written, it will not remember the governor’s declarations of progress. It will remember the pensioners blocking Government House, the civil servants roasting corn after lectures, the nurses hawking goods in secret, the union leader bleeding on the streets of Owerri.

And it will record this verdict: in Uzodinma’s Imo, the wages of labour were not wages at all, but betrayal.

Part 5: Looters’ Rally

In Uzodinma’s Imo, politics became a carnival of cronies, and rallies were parades of looters.

Introduction: The Carnival of Corruption

In most democracies, rallies are theatres of hope—occasions where citizens gather to hear visions for the future. In Uzodinma’s Imo, however, rallies became carnivals of opportunism, gatherings where cronies, fixers, and political jobbers strutted under the governor’s banner. They were not forums for debate but assemblies of those feeding from the state purse.

Africa Daily News (2023) aptly described Uzodinma’s rallies as an “assemblage of gangs of looters.” This was no metaphor—it was the lived reality. Investigations and arrests confirmed that many of those closest to the governor, entrusted with public responsibilities, were themselves implicated in racketeering, fraud, and land-grabbing.

Imo was not governed by institutions—it was governed by a network. And that network was not a system of service, but a cartel of extraction.

The Arrests That Exposed the Machine

In March 2024, ThisDay reported the arrest of Uzodinma’s Special Adviser on Land Recovery over allegations of land racketeering. The police statement revealed systemic abuse of office—public lands converted to private wealth, titles manipulated, ordinary citizens dispossessed.

Barely two months later, Grassroot Reporters covered the arrest of another close aide, the former Special Adviser on Special Duties, Chinasa Nwaneri, again over land-related fraud.

The pattern was unmistakable: advisers tasked with governance had become merchants of public property, selling off land as though Imo’s heritage were a private estate.

Then came the EFCC’s August 2025 announcement: the Court of Appeal upheld the conviction of a former Imo commissioner for fraud and abuse of office. While this was technically tied to an earlier administration, the broader picture was clear—state-level graft was not episodic, it was systemic. Uzodinma’s government sat comfortably in that tradition.

The Politics of Cronyism

Cronyism is not simply about corruption; it is about how power is organized. Under Uzodinma, the machinery of government was redesigned to serve cronies.

- Contracts inflated and recycled: The same project awarded multiple times under different names.

- Advisers empowered as “godfathers” of land, contracts, and even security.

- Budgets manipulated to funnel resources into “optics” projects, propaganda, and banquets.

The message was clear: loyalty, not competence, determined access. And loyalty was rewarded not with honor but with loot.

The Numbers Behind the Feasting

It is easy to dismiss talk of “looting” as rhetoric. But budgets tell the truth. When you examine Imo’s allocations between 2020 and 2025, the priorities are unmistakable.

Table 5.1 – Budget Allocations by Category (2020–2025)

Source: ICIR Budget Analysis, OpenNigeriaStates, BudgIT, MouthpieceNG

| Year | Health (₦bn) | Education (₦bn) | Infrastructure (₦bn) | Refreshments (₦bn) | Convoys/Logistics (₦bn) | PR/Media (₦bn) |

| 2020 | 7.8 | 14.2 | 19.5 | 1.1 | 3.4 | 2.2 |

| 2021 | 8.5 | 15.1 | 20.7 | 1.4 | 3.9 | 2.6 |

| 2022 | 9.1 | 16.0 | 22.4 | 1.7 | 4.2 | 2.9 |

| 2023 | 9.3 | 17.5 | 23.1 | 2.0 | 4.8 | 3.5 |

| 2024 | 9.6 | 18.4 | 22.7 | 2.3 | 5.1 | 4.1 |

| 2025 | 10.0 | 19.2 | 24.3 | 2.7 | 5.8 | 4.5 |

Observation: By 2025, Uzodinma allocated more to refreshments, convoys, and propaganda combined than to health—proof that state resources were feasts for elites, not services for citizens.

FAAC Inflows vs. Development Delivered

The looters’ rally was not funded by air. It was funded by FAAC inflows—billions delivered monthly from Abuja, meant for citizens, consumed by cronies.

Table 5.2 – FAAC Inflows vs. Project Delivery (2020–2024)

Source: MouthpieceNG, BudgIT, OpenNigeriaStates

| Year | FAAC Inflows (₦bn) | Projects Promised | Projects Delivered | Delivery Rate (%) |

| 2020 | 55.2 | 42 | 7 | 16% |

| 2021 | 64.5 | 56 | 11 | 19% |

| 2022 | 68.9 | 61 | 13 | 21% |

| 2023 | 72.4 | 58 | 9 | 15% |

| 2024 | 75.1 | 64 | 12 | 19% |

Impact: Despite ₦336 billion in FAAC allocations over five years, project delivery stagnated below 20%. The money flowed, but development stalled. Where did it go? Into the machinery of cronies.

The Symbolism of Abandoned Projects

Nothing illustrates looting more than failure. When projects are budgeted, announced, and abandoned, the money has not disappeared into thin air—it has been stolen.

Table 5.3 – Failed / Abandoned Projects in Imo (2020–2025)

Sources: Eastern Updates, Grassroot Reporters, BudgIT

| Project | Budgeted (₦bn) | Status | Notes |

| Ubowalla Road (Owerri) | 3.2 | Abandoned | Washed away after ribbon-cutting |

| Orlu Teaching Hospital | 4.5 | Uncompleted | Site deserted, equipment missing |

| Imo Digital Academy | 2.7 | Ghost Project | Exists only on paper |

| Oguta Industrial Park | 5.1 | Ongoing 4 years | No infrastructure visible |

| Ihitte Bridge | 1.9 | Incomplete | Funds disbursed, no bridge |

Total: ₦17.4bn budgeted, little or nothing to show.

These projects became theftmemorials—monuments to promises betrayed.

What Africa Daily News called a “gang of looters” was not metaphor. It was governance reality. Advisers arrested for fraud, cronies feeding on land rackets, billions wasted on propaganda and refreshments while hospitals rotted.

The tables tell the truth: allocations bent towards indulgence, inflows devoured, projects abandoned. This was not governance—it was a looters’ rally masquerading as politics.

Part 6: Drunk on Power

In Uzodinma’s Imo, authority is not service but intoxication—a high that blinds governance to responsibility.

Introduction: The Theatre of Intimidation

Power, at its best, is a sober responsibility. But in Imo under Governor Hope Uzodinma, power has often appeared less like stewardship and more like intoxication—unrestrained, domineering, and obsessed with spectacle.

From the brutalization of Nigeria Labour Congress President Joe Ajaero on the streets of Owerri, to a state budget that allocated billions to “refreshments” while hospitals languished, to the revolving door of legislative speakers impeached like pawns, the optics suggest not governance, but indulgence.

Africa Daily News captured the essence in 2023: Uzodinma’s rule has become synonymous with “notoriety and power intoxication.”

The Ajaero Incident: A Case Study in Overreach

On November 1, 2023, workers in Imo gathered under the NLC banner to protest unpaid salaries and pensions. Their grievances were economic; their demands simple: pay us what we are owed.

Yet the government’s response was not negotiation, but brutality. As reported by Punch, Channels, and Arise News, labour leader Joe Ajaero was dragged, beaten, and left hospitalized. Images of his swollen face became a national symbol of the dangers of dissent under Uzodinma’s rule.

The optics were devastating: a state government responding to wage protests not with dialogue, but with force. In that moment, Uzodinma’s administration projected not strength but intoxication—a governor so consumed by authority that criticism itself became a crime.

The incident was more than an assault on a man. It was an assault on the principle that workers have the right to question power.

The Budget of Excess: ₦2.3 Billion for Refreshments

If the Ajaero episode symbolized coercive overreach, Imo’s 2024 budget symbolized fiscal intoxication. According to ICIR Nigeria, the government allocated an astonishing ₦2.3 billion to “refreshments and meals”, while dedicating less than 4% of its budget to health.

The optics are damning. In a state where hospitals lack drugs, doctors strike over arrears, and citizens die from preventable illnesses, the government prioritized feasting over healing.

This was not a miscalculation—it was a statement of values. It signaled that power in Imo was not about service to the sick or investment in the vulnerable, but about indulgence for those at the table of authority.

The numbers read like satire: billions for banquets, crumbs for clinics. In this way, the budget became another instrument of intoxication—feeding cronies while starving citizens.

The Legislature in Chaos: A Revolving Door of Speakers

Democracy requires balance, and the legislature is meant to be a counterweight to executive power. In Uzodinma’s Imo, however, the House of Assembly became a stage for chaos, with speakers impeached and replaced at dizzying speed.

- In November 2021, Vanguard reported the impeachment of Speaker Paul Emeziem by 19 of 27 lawmakers.

- By January 2022, Daily Post detailed further crises, marking a cycle of instability.

- By September 2022, TheCable noted that Imo had its fourth speaker in just three years—a record of dysfunction.