“Culture is not entertainment, but power.”

By Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Investigative Journalist | Public Intellectual | Global Governance Analyst | Health & Social Care Expert | International Business/Immigration Law Professional

Prologue: The Man Who Refused Silence

There are artists, and then there are architects of history. Fela Aníkúlápó Kútì belongs to the latter order, those rare visionaries who transform music into movement, rhythm into resistance, sound into sovereignty. To speak of Fela is to speak not of entertainment but of insurgency. His art was never an accessory to power; it was its most persistent adversary.

Born in colonial Nigeria, raised in the turbulence of independence, and forged in the crucible of exile and return, Fela carried within him the contradictions of the African twentieth century. He was at once musician and philosopher, hedonist and ascetic, prophet and provocateur. To some, he was dangerous. To others, divine. But to all who heard him, he was unforgettable.

Afrobeat—his invention, his gospel, his weapon—was more than a genre. It was an operating system for resistance. Built on polyrhythmic grooves, horn blasts, and pidgin invectives, it dismantled the machinery of authoritarianism and mocked the hypocrisies of global imperial power. Every note was a charge sheet, every performance a tribunal, every album a manifesto. Where politicians issued decrees, Fela issued basslines. Where soldiers patrolled streets, his rhythms patrolled memory.

But Fela was not content with music alone. He built a republic, declared independence from a corrupt state, and transformed a nightclub into a parliament of the people. He suffered raids, arrests, imprisonment, and exile, yet refused to be broken. Each assault deepened his defiance. Each scar was another verse. Each silence imposed upon him became another song waiting to be born.

This series, Fela Lives: Afrobeat as Global Political Power, does not approach him as myth or relic. It approaches him as blueprint. For Fela is not finished. His rhythms echo in London jazz clubs and São Paulo favelas, in protest squares from Lagos to Minneapolis, in academic conferences and dance floors alike. His voice is still weaponized against tyranny, still instructing new generations that art must risk everything or risk irrelevance.

Fela lives because he remains necessary. He lives because every age of injustice needs its soundtrack. He lives because Afrobeat is not nostalgia, but a pulse that continues to summon courage where fear thrives. To study Fela is not to look back, but to look forward—toward the futures he insisted were possible.

Part 1: The Immortal Pulse: Why Fela Lives

His music did not end with him — it began with us.

“Fela Lives” is not simply a metaphor. It is a truth born of sound, fury, conviction—and a body of work so charged that, decades after his death, Fela Aníkúlápó Kútì resonates not only across diasporas but into the future. To understand why Fela lives is to understand that Afrobeat is more than music: it is political ontology, aesthetic resistance, and a doctrine of self‑determination.

Early Roots: Family, Education, and the Making of the Dissident

Fela was born in 1938 in Abeokuta, into a family that carried both privilege and pressure. His father, Reverend Israel Oludotun Ransome‑Kuti, was a school principal and a Protestant minister; his mother, Funmilayo Ransome‑Kuti, a women’s rights and anti‑colonial activist. From them, Fela inherited two persistent traits: moral urgency and a disdain for injustice.

Educated abroad, immersed in both Western musical tradition and African heritage, Fela absorbed jazz, funk, highlife, Yoruba rhythms. He studied in London; he responded to the black consciousness movements of his time. These were not mere influences. They were tools. He returned to Nigeria not to reproduce colonial legacies or simply entertain, but to ignite something—an electrified patriotism fused with critique.

The Kalakuta Republic: A Space of Refusal

In declaring independence—symbolic but fiercely real—from the state, Fela established the Kalakuta Republic. It was part commune, part performance space, part studio, part shelter. The edifice of Kalakuta was both literal and symbolic: homes, a recording studio, the gathering place for collaborators and dissenters.

The military government regarded it as subversive. In February 1977, around 1,000 soldiers attacked Kalakuta. They razed it. They brutalized its inhabitants. Fela’s mother—Funmilayo—was thrown from a second‑floor window. She died later, from injuries. Fela himself was injured and imprisoned. Deep wounds, both personal and systemic, yet far from extinguishing Fela’s voice. These tragedies became fuel; they reinforced that his art was inseparable from risk.

The Sonic Architecture: Rhythm as Politics

What distinguishes Afrobeat under Fela is its structure: extended grooves, call‑and‑response, horn blasts, polyrhythmic percussion, interludes of improvisation. There is swing, there is pulse, there is dance—but behind the dance is a searing critique.

Take “Zombie” (1977): it lampoons the Nigerian army by comparing soldiers to zombies—obedient, unthinking. The rhythm is aggressive, the horn section braying, the lyrics cutting. When the state responded with violence, it was not surprised. Fela had set the stage for confrontation.

Or “Sorrow, Tears and Blood,” written in wake of pain. It laments civilian suffering, the betrayal of nation. Its message is both local and universal. The specific becomes symbolic: colonial legacies, postcolonial governance, imperial overreach. Each drum, each horn, each voice becomes part of a political sentence.

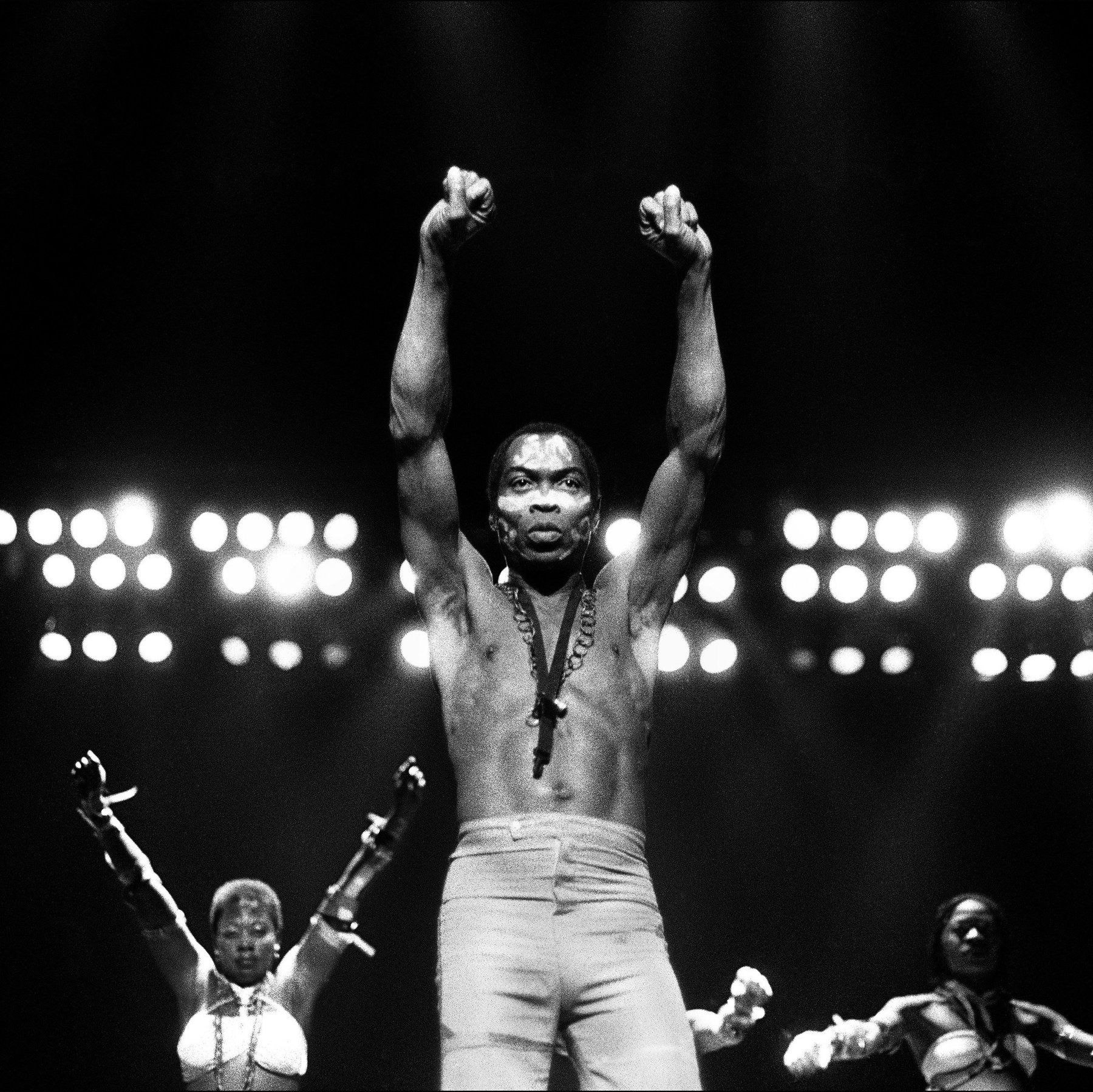

Fela’s Public Self: Performance, Persona, and Embodied Critique

Fela did not merely sing. He staged. His performances were rituals of dissent. The stage was his pulpit; the Shrine his cathedral. He wore flamboyant garb, danced in defiance, invited confrontation with power.

He embraced controversy: polygamy, outspokenness, opposition to religious orthodoxies. These were not calculated for shock alone, though they did provoke. They were woven into his message: that colonial moralities, postcolonial hypocrisies, must be disrupted. The body, the self, the public persona—these were as crucial as the microphone and the stage.

Afrobeat as Political Doctrine

Fela’s lyrics addressed military juntas, corruption, police brutality, economic exploitation. But his doctrine was not confined to lyrics. Afrobeat functioned as embodied political philosophy: rhythm as resistance; sound as sovereignty; culture as refuge and weapon.

For example, when the state tried to silence him, destroying studios and intimidating witnesses, he persisted. Each new album, each live show at the Shrine, was a renewal. He constructed his own digital and analog media channels. He circulated tapes. He held space with his community. His music was not entertainment. It was a living pamphlet.

Global Reverberations: Diaspora, Influence, Legacy

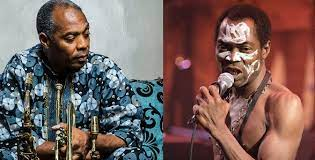

Since Fela’s death in 1997, the grooves of Afrobeat have crossed borders. His sons Femi and Seun carry forward his mission—not as replicas, but as heirs who reinterpret and amplify. Femi’s jazz‑inflected progressive Afrobeat; Seun’s Egypt‑80 continuing the horn sections, the political barbs, the relentless beat.

Artists across continents—Africa, Europe, Americas—sample Fela, reimagine him. Activists invoke his songs in protest movements: his voice is part of chants in EndSARS, part of global Black Lives Matter, part of cultural curricula. His music is taught, archived, critiqued, revered. The Shrine itself (Old and New) holds festivals, laboratories of culture. A museum exists. His influence persists in menus, in art exhibits, in political essays. The local is global. The heritage is urgent.

Why He Still Matters Now

We live in an era where protest songs still terrify regimes; where surveillance, state violence, economic exploitation continue; where race, identity, migration, belonging are contested. Fela’s voice is alive because what he sang is far from resolved.

In a global moment of populism, authoritarian resurgence, digital disinformation, climate injustice, racial inequality—his model of art as political risk, of culture as claim to dignity—is more relevant than ever. When governments silence the press, the musician becomes necessary; when truth is policed, songwriters are witnesses. Fela offered not perfection, but imperative: to speak, to resist, to live.

The Moral Imperative of Listening

To listen to Fela is not passive. One must become attentive. To hear Afrobeat is to hear history, to hear rage, to hear longing, to hear labor. It is to understand that sound is memory. It is to perceive that every drumbeat is a measure of unfreedom, each horn blast a summons toward justice.

Beyond the music lies a doctrine: art must matter. If the artist is not dangerous, why make art at all? That was Fela’s unspoken question. And in that question lies “why Fela lives.” His legacy demands we don’t merely consume, but respond. That we ask: how are we living? In what systems? Under what power? With what courage?

Conclusion of Part 1: Fela’s Eternal Pulse

Fela lives because his pulse is eternal. Because the injustices he stood against persist; because those who hear him are compelled—not simply to nod or dance, but to reckon. He lives in the crack of authoritarianism, in the breath of protest, in the laughter of resistance.

Afrobeat under Fela was never a style only, but a manifesto. It lived in drums, in people, in spaces, in communities that refused erasure. It lives now in younger creators retooling his strategies; in global cities pulsing with diaspora; in festival circuits, academic halls, museum installations. Fela lives, and Afrobeat is global political power because he made it so.

Part 2: Shrine Diplomacy — The Lagos Laboratory of Revolution

A nightclub became a parliament, and rhythm its law.

To fully grasp the insurgent genius of Fela Aníkúlápó Kútì, one must enter the geography of his revolution—not metaphorically, but physically. The Shrine was never just a performance space. It was a cultural embassy, an anti-state, a laboratory where sonic resistance was brewed nightly in full public view. It was the diplomatic capital of Afrobeat, where music became language, ritual became governance, and resistance became form.

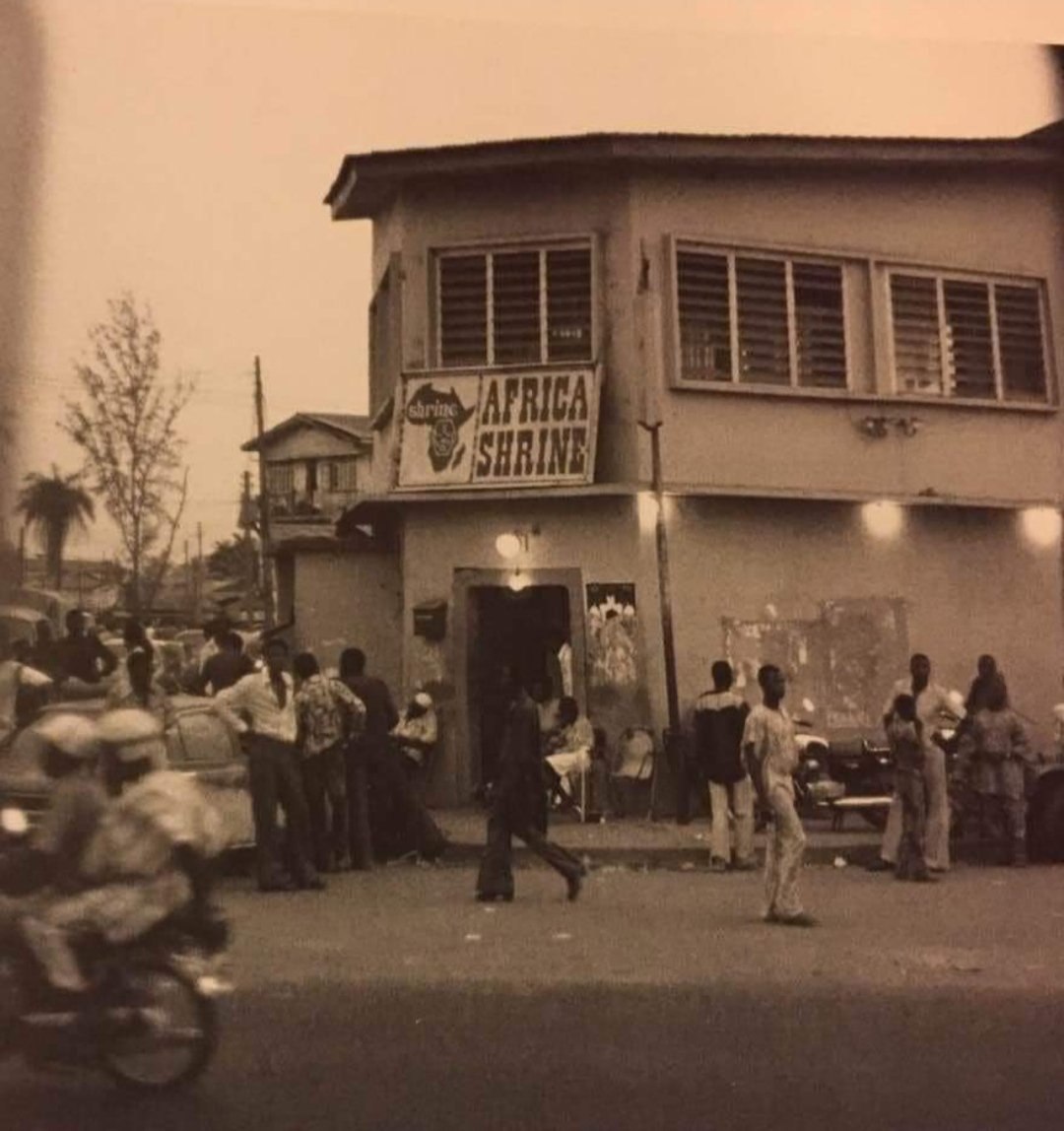

The Shrine as Spatial Resistance

The original Afrika Shrine—established in 1970 on Pepple Street in the Surulere district of Lagos—was neither opulent nor hidden. It was raw, almost ascetic, but vibrated with a frequency unmatched in West Africa’s post-independence artistic scene. Strung together with concrete and plywood, it became the pulsating heart of Afrobeat and the very site where sound was transformed into a political act.

Within its walls, every beat was confrontation. The Shrine was a site of spatial resistance—an arena where Fela built what James C. Scott might have called a “hidden transcript”: a space where the oppressed speak freely, perform their truths, and re-script the master’s narrative. Unlike state-owned cultural institutions, the Shrine was unregulated, uncensored, unsilenced.

The performance nights—especially the legendary “Yabis Nights” held on Saturdays—were less concerts and more public exorcisms. Fela would begin with extended musical introductions, then pause, mid-performance, to offer monologues: satirical, philosophical, often dangerous. These were moments of radical pedagogy, where the crowd learned, unlearned, and re-learned their relationship to power. It was, in every sense, revolution with a rhythm section.

Kalakuta Republic: A Counter-State

Adjacent to the Shrine, Kalakuta Republic functioned as a kind of anti-government in miniature. Declared sovereign by Fela himself, Kalakuta was home to his band members, his family, his multiple wives, and collaborators. It had its own communal governance structure, security, and internal economy. At its peak, Kalakuta was home to over 100 people—a utopian experiment in Afrocentric living, outside state reach.

This act of secession was not symbolic. It was war. By declaring Kalakuta independent, Fela was not merely mocking Nigerian sovereignty; he was rejecting the very legitimacy of post-colonial statehood rooted in corruption and foreign economic dependency. Kalakuta, and by extension the Shrine, became the most subversive architectural idea in Nigeria at the time: a self-sustaining Black microstate.

The Nigerian government, predictably, saw this as an existential threat. What followed were multiple police raids, arbitrary arrests, and the infamous 1977 military attack. During that raid, soldiers set Kalakuta ablaze, threw Fela’s elderly mother out a second-story window, and razed the building. Fela was beaten. The Shrine was desecrated. Kalakuta was destroyed. But the idea? It survived.

Diplomacy Through Drum Patterns

Fela’s form of “Shrine Diplomacy” was different from traditional diplomacy because it did not seek permission. It did not lobby. It declared. His messages were not white papers—they were percussion-driven, bass-heavy, multi-layered compositions that moved like diplomatic cables across urban Lagos, then across oceans.

Take, for example, the way in which Fela would address government officials: he gave them titles—“International Thief Thief” (ITT), “Beast of No Nation,” “Mr. Follow-Follow.” This was satirical diplomacy: naming and shaming, parody as policy. Each song was an open letter, a declaration of disapproval, a communiqué from the “Minister of Vibes & Justice” to the world.

Afrobeat’s structure itself mirrored his political style. Long, improvisational intros—akin to diplomatic overtures—followed by a lyrical blitz of accusations and imperatives. His concerts functioned as summits of dissent where the people came not just to dance, but to be briefed.

The Shrine as Pedagogical Space

More than anything, the Shrine was a school. But not the colonial classroom—this was an African epistemology in real time. Fela would break down the logic of economic exploitation, IMF deals, domestic militarism, religious hypocrisy—all within the rhythm of a 15-minute instrumental break.

Scholars of postcolonial education, such as Paulo Freire and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, would have recognized the pedagogy: dialogic, participatory, culturally rooted. At the Shrine, no one was neutral. The crowd learned politics through movement, through lyrics, through observation. Fela’s dancers—erotic, mythic, powerful—embodied feminism, countering the Western liberal gaze. His use of pidgin English made complex ideas accessible to all. The Shrine taught. Not in the didactic sense, but in the revolutionary one.

Women at the Core: Queens of the Shrine

Fela’s engagement with gender is complex—deeply problematic in parts, progressive in others. His many marriages (27 in one day), his perceived objectification of women, his patriarchal worldview—all have been rightly critiqued. Yet, within the Shrine, women were central: as dancers, vocalists, spiritual leaders, and political anchors.

The Kalakuta Queens, as they were called, were more than stage props. They were cultural ambassadors, each a carrier of the Afrobeat gospel. Their choreography was not ornamental but encoded: movements that referenced Yoruba cosmology, African sexual autonomy, and refusal of colonial femininity. In embodying radical freedom, they became co-architects of Fela’s cultural revolution.

Even Fela’s mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti—matriarch of Nigerian feminism—was a spiritual force in the Shrine, long after her death. Her portraits adorned the walls; her activism shaped Fela’s moral compass. The Shrine was never only male space. It was gendered, yes, but full of contestation and contradiction—just like Fela himself.

The Global Shrine: Diaspora, Digitality, and Reinvention

Today, the physical Afrika Shrine has been rebuilt in Ikeja by Femi Kuti, and functions not only as a live venue but as a pilgrimage site. Presidents, artists, journalists, and global audiences visit it, seeking connection to the legend. But the real Shrine is now global. It lives in the remixes of DJs in Berlin, in the political essays of diaspora writers, in the digital reimaginings of new-age Afrobeat artists.

In São Paulo, Afrobeat collectives play under murals of Fela. In Paris, entire music festivals are structured around the Shrine’s ethos. In Lagos, annual Felabration events draw tens of thousands. The architecture has evolved—but the ritual continues.

The Shrine today is deterritorialized. It is no longer bound by Lagos geography. It is an idea, an exportable ethic. In this way, Fela created not just a space, but an archetype: the counter-cultural institution, free from donor aid, free from Western cultural gatekeepers, beholden only to the people.

Conclusion of Part 2: The Embassy of Dissent

In the end, the Shrine was not just a nightclub. It was a Ministry of Cultural Defense. It was a sovereign state with its own rituals, laws, and liturgies. Fela was not merely an artist; he was its President, philosopher-king, and high priest.

The Nigerian state, despite its tanks and decrees, could never fully conquer it. Because the Shrine was not simply a building. It was an idea—and ideas, once released into rhythm, are impossible to contain.

Fela’s Shrine diplomacy—radical, performative, confrontational—offered a model for cultural sovereignty that transcends geography. In a time when institutions are increasingly co-opted or corrupted, the idea of the people’s embassy of dissent remains not only relevant, but necessary.

Part 3: Sonic Warfare — Afrobeat as Anti-Imperial Strategy

Every horn blast a bullet, every groove a manifesto.

To reduce Afrobeat to music is to misunderstand its purpose. Under Fela Aníkúlápó Kútì, Afrobeat became an arsenal, a sonic armament for African self-determination. It operated not just on the auditory level, but at the level of symbolic power, psychological liberation, and systemic disruption. If the post-colonial state inherited the bureaucratic violence of empire, Afrobeat became its sonic resistance, and a form of cultural warfare more potent than bullets.

Rhythm as Tactic: Compositional Warfare

The first weapon in Fela’s arsenal was the structure of the music itself. Unlike Western pop’s three-minute sugar rush, Afrobeat under Fela often stretched beyond 10, 15, sometimes 20 minutes per track. Each song was a theatre of rhythm, meticulously composed to mirror the long arc of oppression and resistance.

The music did not begin with lyrics; it began with groove architecture. Drums layered atop congas, polyrhythmic percussion counterpointed by syncopated basslines, horn sections erupting like declarations of war. The long intros—far from filler—were tactical: they disarmed the listener, drew them into the trance of resistance before Fela’s voice ever arrived.

In “Colonial Mentality” (1977), the horns declare war. In “No Agreement” (1977), the bassline insists on noncompliance. In “Water No Get Enemy” (1975), the softness of tone masks a deeper critique: submission can be strength when strategically deployed. This was sonic chess, and Fela always played the long game.

Pidgin as Code: Language of the Street, Language of Power

Fela’s choice of Nigerian Pidgin English over Yoruba or Standard English was not aesthetic—it was a revolutionary decision. Pidgin was the lingua franca of the oppressed, accessible to market women, bus drivers, factory workers, and students alike. It undermined colonial linguistic hierarchies and refused the elitism of state officialdom.

But more than accessibility, Fela’s pidgin was coded resistance. His phrases carried layered meanings: “zombie” wasn’t just a slur—it was a metaphor for post-colonial military automatons. “International Thief Thief” (ITT) wasn’t just wordplay—it was an exposé of multinational corruption. Pidgin made it impossible for the elite to hide behind bureaucratic doublespeak.

In this way, Afrobeat became counter-propaganda: where the state spoke in decrees, Fela responded with groove and slang; where they used silence and surveillance, he used street talk and speakers.

The Body as Battlefield: Dance, Discipline, Defiance

Afrobeat is inseparable from movement. Fela’s dancers were not background—they were co-strategists. Their movements were codified language: hips rejecting Victorian morality; footwork drawing from Yoruba ancestral rites; synchronized routines evoking military formations, now repurposed for defiance.

To dance at the Shrine was to reclaim the African body from colonial shame and religious repression. It was to declare: the body is not sin, but sovereignty.

Even Fela’s own stage presence was militant: bare-chested, lean, commanding, with a saxophone slung like a rifle. He moved not to entertain but to command space—to interrupt, to provoke, to decolonize the gaze. In this way, the entire stage became a theatre of anti-imperialism, choreographed in rhythm, lit by resistance.

Afrobeat and the Global South: Transnational Resonance

Afrobeat was born in Lagos, but its message carried across borders. In Cuba, it echoed through Latin jazz and militant salsa. In Brazil, it met samba and candomblé, becoming an anthem of Black consciousness. In South Africa, Afrobeat found kinship with mbaqanga and the protest songs of the anti-apartheid struggle. In Palestine, sampled beats and lyrics appear in youth resistance tracks. Afrobeat was borderless solidarity.

This was not accidental. Fela was deeply aware of the Third World solidarity movements. He referenced Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, Amílcar Cabral. He studied Pan-Africanist theory. His Afrobeat was not isolated—it was plugged into the global struggle against imperialism, capitalism, and cultural erasure.

In this sense, Afrobeat was the soundtrack of the Bandung generation, the sonic articulation of Non-Aligned defiance.

Censorship, Arrest, Surveillance: State Repression as Feedback Loop

The Nigerian state—and its Western-backed apparatus—treated Fela not as a nuisance but as an existential threat. His albums were censored. His concerts surveilled. He was jailed over 200 times. In 1984, under Buhari’s military regime, Fela was sentenced to five years in prison on fabricated currency charges.

The state underestimated something critical: repression only amplified Fela’s message. Every arrest became a lyric. Every raid became a beat. He weaponized victimhood, turning pain into platform.

In the liner notes of Coffin for Head of State (1981), Fela describes placing his mother’s coffin at the doorstep of Nigeria’s military headquarters. That act, symbolic and theatrical, became immortalized in song—a symphony of vengeance without violence.

This was sonic warfare at its most refined: Fela didn’t need guns. His weapons were vinyl, saxophones, speakers, and belief.

Afrobeat vs. Western Soft Power: Culture as Containment

While the West celebrated Fela’s music, its institutions largely sanitized his message. Western journalists marveled at his stagecraft but downplayed his Marxist politics. Western record labels distributed his albums but pressured him to shorten his tracks for radio.

This tension mirrored a broader imperial strategy: commodify dissent to neutralize it. Fela resisted. He refused to dilute his music for airtime. He turned down awards. He walked out of corporate deals. He maintained full control over his output—even when it meant economic hardship.

In doing so, Fela revealed the limits of Western cultural diplomacy. Afrobeat under Fela could not be co-opted, because its integrity was its weapon. His refusal to participate in global capitalist circuits made him a true anti-imperial artist—rare, uncompromising, and therefore dangerous.

Militancy Without Militias: The Philosophy of Sonic Insurgency

Fela’s Afrobeat did not call for armed revolution. It called for cognitive revolution. He wanted his people to think, to question, to feel. His revolution was existential, not paramilitary.

This distinction is crucial. In a post-colonial state marked by coups, guerrilla warfare, and political violence, Fela offered another way: revolution through rhythm. His army was the crowd. His bullets were notes. His slogans became chants. His concerts were protests. His albums were manifestos.

In many ways, he anticipated the tactics of today’s social movements: decentralized, memetic, rhythmic, performative. Afrobeat was militancy without militias, insurgency through syncopation.

Conclusion of Part 3: The Sound that Fights

Afrobeat was never just music. It was a strategy. A weapon. A mode of resistance that bypassed censorship, circumvented borders, and infiltrated minds. Fela understood that empires fall not only through revolution, but through rhythmic disobedience.

In the battle between power and people, sound was his sword. He made music that governments feared. That institutions couldn’t digest. That history cannot forget.

This was sonic warfare. And Fela was its field marshal.

Read also: Shoot Like Hollywood: Make Skits & Films With iPhone

Part 4: Echoes in the Diaspora — The Global Afrobeat Intelligentsia

From Lagos to London, Afrobeat is theory in motion.

Afrobeat was born in Lagos, forged in the crucible of Nigeria’s post-independence struggles and the turbulent reign of military dictatorships. Yet, almost from its inception, the genre was encoded with diasporic DNA. Fela Aníkúlápó Kútì’s Afrobeat was a local insurgency, but its pulse resonated far beyond Nigeria’s borders. It drew from global Black traditions—American jazz, James Brown’s funk, Ghanaian highlife—while speaking back to imperial metropoles with unflinching defiance. It was never meant to stay contained.

Today, Afrobeat lives not only in Lagos but in London, New York, Havana, Bahia, Paris, and Johannesburg. It lives in music festivals, archives, Broadway musicals, academic syllabi, and protest marches. It lives in the work of Fela’s children, in the grooves of new Afro-diasporic bands, in the classrooms of ethnomusicologists, and in the chants of demonstrators who find in his lyrics an inexhaustible arsenal of resistance. Afrobeat has become not just a genre but an intellectual tradition, animated by a global intelligentsia of musicians, writers, activists, and scholars.

This diaspora does not merely imitate Fela; it interprets him. They keep his memory alive, not as static nostalgia, but as a living methodology. The global Afrobeat intelligentsia constitutes a council of voices who consult Fela as one might consult Fanon, Baldwin, or Ngũgĩ. His work is not memorialized—it is mobilized.

London: The Second Capital of Afrobeat

London occupies a special position in Afrobeat’s diasporic geography. It was here that Fela studied trumpet and piano at Trinity College of Music in the late 1950s. It was here that he encountered highlife musicians from Ghana and Sierra Leone, and absorbed jazz from the city’s thriving Black communities. Later, in 1969, his time in Los Angeles—meeting Sandra Izsadore and Black Panther activists—would radicalize his politics, but London provided the early soil.

Decades later, London has become one of the strongest Afrobeat hubs outside Nigeria. Bands such as Kokoroko, Ezra Collective, and Sons of Kemet do not reproduce Fela’s sound note-for-note, but weave Afrobeat’s polyrhythms into a distinctly London-based idiom. They combine jazz improvisation with Afrobeat grooves, grime’s urban urgency, and the political consciousness of diasporic Britain. Kokoroko’s breakout hit Abusey Junction (2018) demonstrates how Afrobeat’s melancholic warmth can be repurposed for new emotional registers. Sons of Kemet, led by Shabaka Hutchings, fuse Afrobeat’s marching rhythms with Caribbean soca and London’s spoken-word tradition, their album Your Queen Is a Reptile (2018) offering a radical critique of monarchy and empire.

Venues such as the Southbank Centre and festivals like We Out Here now regularly stage Afrobeat performances and panel discussions. British-Nigerian intellectuals, including Teju Cole, have invoked Fela in essays and lectures, treating his work as both cultural archive and moral compass. London, in effect, has become Afrobeat’s second capital: a site where its pulse merges with the complexities of diaspora identity, migration, and resistance.

The United States: Afrobeat and Black Radical Continuities

In the United States, Afrobeat has found a home in the Black radical tradition. Fela’s time in Los Angeles during 1969 coincided with the height of the Black Power movement. Under the influence of Sandra Izsadore, a member of the Black Panther Party, Fela absorbed the language of self-determination, Pan-Africanism, and cultural militancy. Afrobeat was forever changed—no longer just sonic experimentation, but a political doctrine.

That connection remains alive in the U.S. today. New York’s Antibalas Orchestra, founded in 1998, has become the leading North American Afrobeat ensemble. Their debut album Liberation Afro Beat Vol. 1 (2000) positioned Afrobeat as a 21st-century language of dissent, while later works such as Who Is This America? (2004) and Where the Gods Are in Peace (2017) connect U.S. imperialism, racial inequality, and global capitalism to Fela’s critique of neocolonial Nigeria. Antibalas even contributed to the Broadway musical FELA! (2008), directed by Bill T. Jones and produced by Jay-Z and Will Smith, which brought Fela’s story to global theatre audiences.

American hip-hop has also absorbed Afrobeat’s DNA. From Mos Def to Questlove, rappers and producers have cited Fela as inspiration. Beyoncé and Jay-Z sampled Fela in their 2018 joint tour, while Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly (2015) resonates with the same ethos of music as manifesto. Afrobeat’s long-form grooves and sharp political critique anticipate the aesthetic strategies of modern Black music in America.

Brazil and Cuba: Afro-Diasporic Dialogues

Afrobeat’s resonance in the Americas extends beyond the U.S. into Brazil and Cuba, where Afro-diasporic traditions have always thrived. In Bahia, home to Brazil’s largest Black population, Afrobeat finds kinship with samba-reggae and axé. Groups such as Afro Ilê and BaianaSystem incorporate Afrobeat’s instrumentation into carnival parades and resistance songs, weaving Fela’s politics into Brazil’s own struggles against racial inequality, police brutality, and economic apartheid.

In Cuba, Afrobeat has entered dialogue with timba, Afro-Cuban jazz, and Santería ritual music. Musicians have reinterpreted Fela’s grooves through the lens of Yoruba spirituality, which remains strong in Cuba’s religious life. Here, Afrobeat feels less like an import than a return—a reunion of separated diasporic siblings across the Atlantic.

These transatlantic echoes demonstrate Afrobeat’s adaptability. Wherever African-descended people confront oppression, Afrobeat offers not just rhythm, but a ready-made lexicon of dissent.

France and the Global Festival Circuit

France has become another stronghold of Afrobeat’s diaspora. Paris, with its large West African communities, has embraced Afrobeat both as music and as political discourse. Festivals such as Banlieues Bleues and Jazz à la Villette have hosted tributes to Fela, while French record labels have reissued his classic albums for new audiences. Murals of Fela adorn Parisian neighborhoods, situating him among the pantheon of diasporic heroes.

Perhaps the most significant diasporic institution is Felabration, founded in Lagos in 1998 by Yeni Kuti, Fela’s daughter. Held annually in October to commemorate Fela’s birthday, Felabration has grown into a global festival, with simultaneous editions in London, New York, Johannesburg, Accra, and beyond. The festival is not simply a celebration of Fela’s memory—it is a convocation of Afrobeat’s living community. Artists, activists, and audiences gather to debate politics, perform resistance, and renew their cultural sovereignty. Felabration embodies the idea that Afrobeat is not a relic, but a ritual: a yearly reaffirmation of freedom through sound.

The Scholars and Writers of the Afrobeat Archive

Afrobeat’s intelligentsia extends beyond musicians into scholarship and literature. Ethnomusicologists such as Michael Veal, whose Fela: The Life and Times of an African Musical Icon remains the definitive academic study, have positioned Afrobeat as central to 20th-century global music. Tejumola Olaniyan’s Arrest the Music! explores Fela’s work as a fusion of aesthetics and politics, while Sola Olorunyomi’s Afrobeat! Fela and the Imagined Continent situates Afrobeat within continental Pan-Africanist thought.

Writers, too, keep Fela alive. Teju Cole has cited Fela as formative to his intellectual development. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has referenced Afrobeat in interviews as part of the cultural landscape that shaped Nigerian identity. Toni Morrison once remarked that Fela’s lyrics rivaled fiction in their immediacy and defiance.

Institutions now preserve his legacy as global heritage. The British Library has archived his recordings, while the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture includes Fela in its collections on transatlantic music and protest. These archives are not mausoleums but living repositories—ensuring that future generations can study Afrobeat not as exotic artifact, but as central cultural philosophy.

The Intelligentsia as Living Council

What emerges from these global echoes is a portrait of the Afrobeat intelligentsia as a living council. Seun Kuti continues his father’s firebrand politics with Egypt 80. Femi Kuti, nominated multiple times for the Grammy Award, has evolved Afrobeat into a jazzier, more globally accessible idiom while retaining its critique of corruption and inequality. Burna Boy, perhaps the most visible contemporary Nigerian artist, channels Fela’s spirit into Afrofusion, bringing political critique into stadiums and Grammys alike. Bands from New York to London reinterpret Fela in their own contexts, while scholars, writers, and festival curators translate his legacy into thought and practice.

This is not a cult of nostalgia. It is not about idolizing a past figure. It is about activating a living methodology. The Afrobeat intelligentsia consult Fela as one consults a theorist, a revolutionary, a prophet. His songs remain blueprints; his life remains a manual. Afrobeat, as carried by its global heirs, remains not entertainment, but power.

Conclusion: Afrobeat as Global Political Language

Fela Kuti once declared that “music is the weapon.” Today, that weapon is wielded by countless hands across the world. From London jazz collectives to New York Afrobeat orchestras, from Brazilian street parades to French festivals, from academic classrooms to digital protest playlists, Afrobeat has become a global political language.

Its diaspora ensures that Fela does not belong to Nigeria alone, nor even to Africa. He belongs to a transnational movement that insists on freedom, justice, and self-determination. Afrobeat’s pulse continues because oppression continues. Its grooves expand because injustice expands. Its intelligentsia multiplies because every generation needs a soundtrack of courage.

The echo is clear: Fela lives. And in the voices of his global heirs, he speaks still—reminding us that rhythm can resist, groove can govern, and music can outlast empire.

The Global Afrobeat Intelligentsia: Who They Are

Today, a constellation of individuals across disciplines carry forward Fela’s DNA. They are not imitators, but interpreters—each extending Afrobeat into new terrains while retaining its militant ethos.

- Femi Kuti: Fela’s first son, and perhaps the most globally recognized custodian of Afrobeat, has spent decades carrying the torch with both fidelity and innovation. Leading his band Positive Force, Femi infused Afrobeat with jazz flourishes, socially conscious lyrics, and an openness to cross-genre collaboration. His multiple Grammy nominations attest not just to musical excellence, but to Afrobeat’s international legitimacy. Unlike his father, Femi has often chosen negotiation over confrontation, but his music remains unflinching in its critique of corruption, inequality, and neocolonial entanglements.

- Seun Kuti: The youngest son, who literally inherited Egypt 80, continues Fela’s firebrand energy with a more radical edge. Seun is not merely a performer but a provocateur, embodying his father’s uncompromising stance against political hypocrisy.

- Burna Boy: With Grammy wins and arena tours, Burna has become the most visible global voice connecting Afrobeat’s rebellious spirit with contemporary Afrofusion. His album African Giant functions as a manifesto of Pan-African pride, channeling Fela’s anti-establishment spirit into a new idiom.

- Antibalas: The New York Afrobeat orchestra, founded in 1998, has become a leading torchbearer of Afrobeat abroad, blending it with critiques of U.S. politics and global inequality. Their involvement in the Broadway musical FELA! brought Afrobeat to mainstream theatre audiences worldwide.

- Ezra Collective and Kokoroko: London-based ensembles weaving Afrobeat with jazz, grime, and soul, representing the sound of the diaspora while keeping the Afrobeat pulse alive for a new generation.

- Scholars and Writers: Ethnomusicologists such as Michael Veal, Tejumola Olaniyan, and Sola Olorunyomi, along with writers like Teju Cole and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, continue to frame Fela’s legacy as both artistic innovation and political philosophy.

Together, this network of musicians, writers, curators, and scholars forms not a cult of memory, but a living council—a posthumous intellectual fraternity where Fela is not merely remembered, but consulted. In their work, Fela is not past tense. He is present, shaping conversations, guiding movements, and haunting stages across continents.

Part 5: State Surveillance & Sonic Dissent — Fela vs. Power

The state could jail his body, but never his rhythm.

If Afrobeat was Fela Aníkúlápó Kútì’s weapon, then the Nigerian state was the adversary that sought relentlessly to silence him. Few artists in modern history have faced such sustained harassment, surveillance, imprisonment, and censorship. Yet paradoxically, it was precisely this constant antagonism that amplified Fela’s stature from musician to myth. The more the state attacked him, the more he grew into a living emblem of dissent, a reminder that even authoritarian regimes tremble before rhythm.

The State as Audience, the State as Enemy

Fela’s music was never meant to flatter power—it was designed to expose it. Songs like Zombie (1977), Coffin for Head of State (1981), and Authority Stealing (1980) directly ridiculed the military regime. Where most artists courted state patronage, Fela weaponized his art against the generals themselves, calling them out by name, shattering the code of silence.

The Nigerian government, accustomed to controlling discourse, suddenly found itself a captive audience. Soldiers attended his concerts not to dance, but to monitor. Spies stood in the back of the Shrine, jotting notes as Fela mocked their masters. His records were scrutinized as though they were leaked intelligence files. Every new release was a threat assessment. In this sense, Fela achieved the impossible: he made the state his unwilling listener.

Kalakuta Under Siege: The Architecture of Repression

The most brutal manifestation of state power came in February 1977, when over a thousand soldiers attacked Fela’s Kalakuta Republic. This was not a raid; it was a siege. The commune was burned. Fela was beaten nearly to death. His elderly mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti—the formidable anti-colonial activist—was thrown from a second-story window, later succumbing to her injuries.

The attack was meant to end Fela. Instead, it immortalized him. His response was not silence, but art as vengeance. He carried his mother’s coffin to the barracks of General Olusegun Obasanjo in a symbolic act of protest, and then released the album Coffin for Head of State. The music was grief turned into indictment, personal tragedy weaponized into public testimony.

This cycle—attack, repression, retaliation through art—became the rhythm of Fela’s life. The state could wound his body, but not his voice.

The Prisoner as Prophet

Fela was arrested over 200 times during his lifetime, often on fabricated charges ranging from currency smuggling to possession of weed. In 1984, under Muhammadu Buhari’s military regime, he was sentenced to five years in prison for allegedly attempting to illegally export money. Amnesty International later declared him a prisoner of conscience, and global campaigns secured his release after 18 months.

Yet prison only elevated his myth. Behind bars, Fela became a prophet. His incarceration exposed the fragility of a state that feared not armies, but melodies. His letters from prison circulated like underground scripture. Each release from jail was staged as a triumphant return, with fans awaiting him as though he were a head of state returning from exile.

Surveillance as Feedback Loop

What is remarkable about the Nigerian state’s relationship with Fela is how much its repression became part of the art itself. The more they censored him, the more dangerous his music became. Each banned record acquired cult status. Each seized album cover became an icon of defiance.

In effect, the government provided Fela with free publicity. By trying to erase him, they canonized him. Surveillance became a feedback loop, ensuring that every confrontation generated new content. The raids were not the end of the song—they were the beginning of the next one.

Global Dimensions of Censorship

Fela’s battles were not confined to Nigeria. His anti-imperial message made Western powers uneasy. Songs like ITT (International Thief Thief) directly accused multinational corporations—particularly ITT, with its deep connections to Henry Kissinger and Nigerian elites—of plundering Africa.

Western media often celebrated his sound while sanitizing his politics. Reviews marveled at the “exotic rhythms” but downplayed the Marxist critique. Record companies pushed him to shorten his tracks for radio play. Fela refused. His resistance was not only to Nigerian generals, but also to Western cultural gatekeeping, which sought to commodify Afrobeat while neutralizing its radicalism.

By rejecting these compromises, Fela became a rare figure: an artist whose work could not be co-opted. His music remained dangerous even in the heart of the West.

Sound as Counter-Surveillance

If the state monitored him, Fela monitored the state. Afrobeat functioned as counter-surveillance: where governments spied on citizens, Fela spied on governments through sound. His songs became archives of misconduct, catalogues of corruption, living documentaries of tyranny.

Authority Stealing accused politicians of embezzlement. Army Arrangement dissected the manipulations of military rule. Beasts of No Nation condemned world leaders like Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, calling them hypocrites complicit in global exploitation.

These tracks are not mere protest songs—they are classified files made public, released on vinyl rather than leaked through whistleblowers. In this sense, Afrobeat was not commentary; it was exposure.

The Body as Evidence

State repression left physical marks on Fela—scars from beatings, injuries from raids. Yet rather than hide them, he displayed them as evidence. His performances were not just artistic—they were testimonial. Each scar was a footnote to a lyric. His half-naked body on stage was not spectacle, but affidavit.

When he appeared gaunt and weakened after imprisonment, it was not defeat—it was indictment. He turned his body into a living archive of state violence, a reminder that repression does not silence, but speaks through wounds.

The Global Witness: NGOs, Media, and Diaspora

By the 1980s, Fela’s persecution drew international attention. Amnesty International, PEN International, and numerous NGOs campaigned for him. Western journalists, initially dismissive, began to recognize the depth of his struggle. African diaspora communities amplified his story, staging concerts, publishing manifestos, and ensuring his voice reached beyond Lagos.

Diaspora solidarity turned Fela from a Nigerian dissident into a global symbol of resistance. He was no longer just a musician under surveillance; he was a witness against authoritarianism everywhere.

Conclusion of Part 5: The State That Could Not Silence

In the contest between Fela and the Nigerian state, the state had guns, prisons, and propaganda. Fela had groove, language, and truth. History has proven whose weapons endured.

Surveillance failed because Afrobeat was not simply sound—it was social memory. You cannot jail a rhythm. You cannot censor a pulse. You cannot burn a groove. Every attempt to silence him only widened his audience.

Fela’s battle with the state demonstrates a universal law: regimes can control bodies, but they cannot control the echoes of dissent once they are set to music. His surveillance file has long been forgotten in government archives. But his albums—Zombie, Sorrow, Tears and Blood, Coffin for Head of State—remain eternal records, still indicting power today.

Fela vs. power was not just a clash of artist and state. It was proof that sound itself can outlast tyranny.

Part 6: Legacy Code — Fela’s Blueprint for Future Creators

Not nostalgia, but a manual for courage.

Legacies often calcify into museums, monuments, and memorials—frozen relics of lives once lived. But Fela Aníkúlápó Kútì’s legacy refuses embalming. It is not a mausoleum; it is a blueprint. What he left behind is not only an archive of music, but a code of living, a philosophy of resistance, a manual for artists seeking to create in defiance of power. Fela lives not because we remember him, but because we still require him.

Art as Risk, Not Ornament

The first and most urgent lesson Fela offers to future creators is this: art must take risks. Too often, art in our time is domesticated, commodified, stripped of its teeth. Fela never allowed his art to be ornamental. He asked not whether a song was beautiful, but whether it was dangerous.

Future creators must resist the seductions of mere entertainment. Beauty without courage is decoration. Fela’s blueprint demands that artists embrace risk: the risk of censorship, the risk of marginalization, the risk of losing markets. For only in risk does art become a weapon, a compass, a shield.

Independence as Infrastructure

Fela built Kalakuta Republic not only as a community, but as a cultural infrastructure independent of state and corporate control. His recording studios, his Shrine, his commune—all were refusals of dependency. He would not wait for grants, record label executives, or cultural bureaucrats. He built his own systems.

Future African creators cannot afford to depend solely on foreign validation, streaming platforms, or state subsidies. Fela’s blueprint insists on building parallel infrastructures: independent studios, community-based distribution, direct-to-audience engagement. Sovereignty begins not with slogans but with structures.

The Local as Universal

Fela wrote in pidgin. He sang about Lagos traffic jams, Nigerian generals, corrupt contractors. His topics were unapologetically local. Yet those songs resonated in Johannesburg, Havana, New York, and London.

The blueprint here is clear: the local is not provincial. It is the doorway to universality. By grounding art in immediate realities—your street, your language, your politics—you paradoxically achieve global relevance. Fela proves that one does not dilute to appeal globally. One deepens, and the world comes closer.

The Body as Medium

Fela taught that the artist’s body is not separate from the art—it is the art. He performed bare-chested, scarred, unfiltered. His body carried the marks of raids and prison beatings, and he turned them into testimony.

For creators, this blueprint is radical: do not outsource your art to abstraction alone. Embody it. Live it. Be willing to let your art inscribe itself on your body—whether through performance, sacrifice, or discipline. The body becomes both canvas and archive.

Defiance as Discipline

Fela was notorious for his excesses: marijuana, polygamy, provocations. But beneath the chaos was discipline—endless rehearsals, meticulous arrangements, relentless performances. He did not stumble into Afrobeat. He engineered it, night after night, horn by horn, beat by beat.

Future creators must recognize that defiance without discipline is noise. The blueprint is to pair militancy with mastery, rebellion with rigor. Only then can art endure.

Global Consciousness, African Sovereignty

Fela was Pan-African, but never naïve. He embraced global solidarity but rejected foreign paternalism. He studied Marx and Lenin, but retranslated them through Yoruba cosmology and African realities.

For future creators, this is the balancing act: to engage globally without losing sovereignty. To collaborate without being co-opted. To build bridges, not dependencies. Afrobeat remains powerful because it is rooted in Lagos soil while branching across oceans.

From Audience to Community

At the Shrine, the crowd was not passive. They were students, comrades, witnesses. Fela blurred the line between performer and audience, turning concerts into assemblies.

For today’s creators, the blueprint is to transform audiences into communities. Fans are not consumers. They are participants, co-creators of meaning. Social media offers new tools for this, but the principle remains: art must organize people, not just entertain them.

Resisting the Temptation of Silence

Every authoritarian regime attempts to silence artists—through fear, censorship, exile, or co-option. Fela’s blueprint is blunt: refuse silence. If censored in newspapers, sing it on stage. If banned from radio, press it on vinyl. If raided at the Shrine, build another Shrine.

For future creators, silence is complicity. Art must speak where others cannot. To be quiet in the face of injustice is to betray the very vocation of the artist.

The Artist as Witness, Prophet, Builder

In the end, Fela’s life crystallizes three roles for future creators:

- Witness: To document the times, to record injustice, to testify.

- Prophet: To see beyond the present, to warn, to dream, to imagine new futures.

- Builder: To construct institutions, communities, and structures that outlast regimes.

Any artist who takes up this triple calling becomes dangerous—and necessary.

The Inheritance: Not a Museum, but a Manual

It would be easy to reduce Fela to nostalgia, to t-shirts, to festival tributes. But his true inheritance is not consumable. It is actionable. His songs are not only grooves but manuals. His life is not only biography but methodology.

Future creators who study him should not merely remix his rhythms but decode his tactics. Afrobeat is not a relic—it is a field guide for surviving and resisting in postcolonial and neo-imperial times.

Conclusion: The Living Blueprint

Fela lives because his blueprint has not expired. Because corruption still thrives, soldiers still march, corporations still loot, and communities still dance as a form of defiance. He lives wherever artists risk careers for truth, wherever creators build institutions outside the state, wherever audiences transform into movements.

For future African creators—and indeed for creators everywhere—Fela’s blueprint demands courage, independence, and imagination. It insists that music must not merely entertain, but liberate. It reminds us that art is not neutral; it is either complicit or resistant.

Fela’s final gift is this truth: the artist’s duty is not to survive power, but to outlast it. And with Afrobeat still pulsing across continents, it is clear that Fela has already won.

Epilogue: The Pulse That Refuses to Die

Legends fade. Monuments erode. Even nations collapse into the rubble of history. Yet Fela Aníkúlápó Kútì endures—not as nostalgia, not as bronze bust or museum artifact, but as vibration. He survives in pulse, in rhythm, in the breath of saxophone and the defiance of drums. His immortality is not metaphor; it is audible. Listen closely—in Lagos traffic, in Brooklyn block parties, in Johannesburg protests—and you will hear it: the refusal to be silenced.

Fela’s life was not tidy. It was chaotic, contradictory, even scandalous. But that was his genius. He was not a saint; he was a storm. He confronted generals with grooves, mocked presidents with pidgin, and built a republic out of rhythm. His failures and excesses make him human, but his courage—unyielding, audacious, uncompromising—makes him eternal.

The lesson for us is simple, though its practice is not: art must matter. In an age when creativity is often domesticated into content, when music is consumed like disposable sugar, Fela reminds us that rhythm can be resistance, that song can be structure, that melody can be manifesto. He challenges us to ask: what good is art if it does not disturb power? What value has beauty if it does not expose brutality?

Around the world, his descendants continue the work. Femi and Seun Kuti extend the Afrobeat republic with fidelity and fire. Burna Boy electrifies arenas with Fela’s irreverent spirit. Writers, scholars, dancers, and filmmakers draw from his arsenal to confront their own regimes, their own empires, their own silences. The global Afrobeat intelligentsia is not a tribute club—it is a parliament in session, still debating, still teaching, still resisting in Fela’s name.

And yet, the greatest tribute to Fela is not to play his music louder, but to live his code. To speak when silence is demanded. To dance when despair dictates stillness. To build when systems collapse. To risk when comfort is offered.

Fela’s life closed in 1997, but his work has no conclusion. Afrobeat is still insurgent, still sovereign, still dangerous. Its pulse carries forward, outlasting coups, outlasting censorship, outlasting every regime foolish enough to believe that rhythm can be jailed.

In the end, Fela’s epitaph is not carved in stone. It is carved in sound. And as long as injustice lives, so too will he. Fela lives—not behind us, but ahead of us.

References

Books

Collins, John. Fela: Kalakuta Notes. Ibadan: Bookcraft, 2009.

Moore, Carlos. Fela: This Bitch of a Life. Expanded edition. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2009.

Olaniyan, Tejumola. Arrest the Music! Fela and His Rebel Art and Politics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004.

Olorunyomi, Sola. Afrobeat! Fela and the Imagined Continent. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2003.

Veal, Michael E. Fela: The Life and Times of an African Musical Icon. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000.

Journal Articles & Essays

Barber, Karin. “Popular Arts in Africa.” African Studies Review 30, no. 3 (1987): 1–78. https://doi.org/10.2307/524162.

Euba, Akin. “Traditional Elements as the Basis of New African Art Music.” African Music 4, no. 3 (1969): 33–39.

Waterman, Christopher A. “Our Tradition Is a Very Modern Tradition: Popular Music and the Construction of Pan-Yoruba Identity.” Ethnomusicology 34, no. 3 (1990): 367–379. https://doi.org/10.2307/851623.

Archival & NGO Sources

Amnesty International. Nigeria: Prisoners of Conscience: The Case of Fela Anikulapo Kuti. London: Amnesty International Publications, 1986.

British Library Sound Archive. “African Popular Music.” Accessed September 2025. https://sounds.bl.uk.

Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. “Afrobeat and the Legacy of Fela Kuti.” Washington, DC: Smithsonian, 2017.