“Insurgency is not marginal. It is the grammar of the present.”

By

Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Investigative Journalist | Public Intellectual | Global Governance Analyst | Health & Social Care Expert | International Business/Immigration Law Professional

Executive Summary

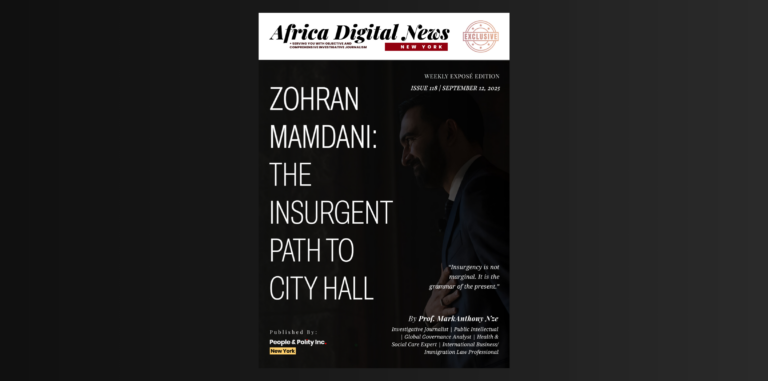

This twelve-part series traces the insurgent rise of Zohran Mamdani — a Ugandan-born, Indian-heritage, Queens-raised assemblyman whose politics embodies both disruption and design. It is not biography but architecture: a literary-political framework that treats Mamdani not as anomaly but as prototype, refracting the contradictions of New York into a blueprint for the American left’s unfinished experiment.

The story opens with Origins of Rebellion, where Mamdani’s diasporic biography — Kampala to Queens — becomes political DNA, echoing Harvard research on how immigrant voices revitalize democracy. The Bronx Crucible follows his adolescence at Bronx Science, where early defeats and cricket-team organizing foreshadow an insurgent trajectory. In Hip-Hop, Housing, and Hustle, Mamdani’s rap persona and tenant counseling reveal the fusion of culture and grassroots struggle that seeds his politics.

The rupture arrives in The Rise Against Empire Politics, where Mamdani topples a four-term Democrat in Astoria, rewriting the grammar of Queens politics. The DSA Blueprint then dissects the machinery behind this victory: Democratic Socialists of America, movement politics, and the translation of anger into power.

Against this backdrop, Cuomo’s Fall, Mamdani’s Surge stages insurgency as counter-empire. As Albany’s prince collapses under scandal, Mamdani advances a politics rooted in fare-free buses and transit justice, framed against Harvard-backed analyses of equity and mobility. The People’s Manifesto extends this insurgency into full architecture: public groceries, a $30 wage, universal health care. Far from utopian, Harvard research grounds these proposals as rational alternatives to systemic collapse.

The battle between Empire City vs. Social City dramatizes the larger conflict: Wall Street panic at the threat of rent justice against tenants’ euphoria at insurgent representation. Harvard studies on housing and eviction provide the statistical spine; Mamdani’s rhetoric provides the insurgent cadence. The Internationalist Mayor widens the lens: Palestine, Modi, and global wage struggles tie Astoria’s streets to diasporic and transnational politics, proving that New York is already a global stage.

But insurgency is also cultural. In The Radical Aesthetic, Mamdani turns politics into performance: memes, scavenger hunts, and rap reframed as instruments of climate justice and collective survival. This insurgency is as much spectacle as statute, aesthetic as administration.

The final arc tests whether insurgency can survive governance. From Aspiration to Administration explores the fragility of turning rebellion into City Hall routine — housing law, racial equity, and bureaucracy as crucibles for insurgent survival. The Future of the American Left closes with a claim: the left’s endurance depends not on Washington gridlock but on cities like New York, where insurgents can embed equity into governance and project it outward.

Mamdani emerges as both product and producer of global currents: an immigrant child turned cultural insurgent, a tenant tribune turned legislative architect. His path to City Hall is more than biography. It is rehearsal for a new grammar of American socialism.

Combining narrative techniques with findings from Harvard research, this approximately 20,000-word series examines a range of political issues from innovative and distinctive viewpoints.

Part 1. Origins of Rebellion

From Kampala to Queens: how displacement, diaspora, and dual heritage forged Mamdani’s political DNA.

1.1 Kampala’s Ghosts

The story of Zohran Mamdani does not begin in Astoria’s rent-burdened apartments or in the chants of a socialist rally. It begins in exile. To understand why a young man would rise to challenge Queens’ entrenched Democratic machine, one must trace the path of rupture that carried his family across continents, through dictatorships, and into the immigrant labyrinth of New York. His insurgency is not accidental; it is inheritance.

The Mamdani name is marked by expulsion. In 1972, Idi Amin ordered the expulsion of Uganda’s South Asian community, uprooting nearly 80,000 people and scattering them across the globe. Among them was Mahmood Mamdani, Zohran’s father — a scholar who would become one of Africa’s most prominent intellectuals. For the young Zohran, this was more than family history. It was a lesson: that citizenship can be revoked overnight, that belonging is fragile, that survival depends on resistance.

The Harvard Law Review (2021) has argued that “race, immigration, and political representation are not separable categories, but constitutive of one another.” This insight is not abstract in Mamdani’s case — it is lived reality. His politics is not the luxury of a safe inheritance but the necessity of a family shaped by exile. Kampala lingers in his speeches, not as nostalgia but as warning: democracy, unless defended, is always provisional.

1.2 Queens as Crucible

Queens offered refuge, but it also demanded reinvention. Here, subway lines stitched together worlds — Colombian bakeries, Bangladeshi mosques, Dominican bodegas. For Mamdani, growing up in this borough meant learning to translate between fragments of identity, to navigate the hyphen of “Ugandan-Indian-American.”

The Harvard Gazette (2020), in its study of children of immigrants, observed that “second-generation leaders are not merely mirrors of their communities; they are active agents transforming them.” Mamdani embodied that transformation. He did not pursue assimilation into the existing order. He used his dual heritage as leverage to imagine a politics that could be at once deeply local and globally resonant.

It is no accident that Queens has birthed some of America’s most disruptive figures — from Donald Trump to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. The borough teaches contradiction: swagger alongside struggle, visibility alongside erasure. For Mamdani, it was both shield and stage, preparing him for a politics that would refuse invisibility.

1.3 The Outsider’s Legitimacy

The Harvard Ash Center (2021) calls outsider candidates “critical to democratic legitimacy,” noting that they often rebuild trust precisely because they do not emerge from entrenched institutions. Mamdani entered politics not as a polished machine loyalist but as a housing counselor, a tenant advocate, a man who had walked Astoria’s streets with clipboards and flyers.

His legitimacy was not inherited through patronage. It was earned, brick by brick, conversation by conversation. The outsider’s paradox defined him: because he did not belong, he could belong more deeply. He represented not just Astoria’s tenants but their sense of exclusion from New York’s political establishment.

But this legitimacy is also precarious. As the Harvard Business Review (2020) notes, outsider leaders “challenge entrenched power structures” while simultaneously being pulled toward the very institutions they seek to disrupt. Mamdani’s insurgency is therefore a balancing act: remaining authentic enough to retain outsider credibility, while learning to navigate the bureaucracies of governance.

1.4 Between Worlds

To live as the child of immigrants is to dwell in an in-between — too foreign for the insiders, too American for the ancestral homeland. But Mamdani transformed this liminality into power. The Harvard Gazette (2022) argued that underrepresented leaders don’t just diversify institutions; they “reimagine the possibilities of governance.”

Mamdani’s speeches bear this dual cadence. When he talks about fare-free buses, one hears not only a local policy proposal but also echoes of broader struggles against dispossession — from Kampala’s exiles to Palestine’s stateless. His identity does not tether him; it expands him. Queens is his home base, but his politics carries the weight of a global diaspora.

1.5 America’s Insurgent Tradition

America has often demanded assimilation from its immigrants: silence your accent, bury your old world, become a citizen who fits. Mamdani flips this script. His trajectory follows what Harvard Kennedy School researchers (2021) describe as the “future of democratic socialism” in America — a movement disproportionately advanced by immigrants and second-generation leaders who refuse absorption.

In this sense, Mamdani is not only Astoria’s assemblyman. He is a chapter in America’s longer insurgent tradition: the outsider who enters the inside without surrendering his rupture, the immigrant who insists that his very difference is the source of renewal.

The Harvard Gazette (2021) summarized it bluntly: “Immigrants are vital to U.S. democracy because they redefine who belongs.” Mamdani’s politics is precisely that redefinition — a refusal to let the lines of belonging be drawn by machine Democrats or Wall Street elites.

1.6 Insurgency Finds Its Vehicle

For Mamdani, the leap from tenant counseling to insurgent politics required a vessel. That vessel was the Democratic Socialists of America — a network that, as Harvard Kennedy School (2021) observed, represents “a reconstitution of political imagination rather than a mere platform of policy.”

Astoria in 2020 became the theater of this insurgency. At a moment when national politics was paralyzed between Trumpian reaction and Bidenite moderation, Mamdani and his comrades offered something that felt both ancient and brand-new: socialism, revived not as Cold War nostalgia but as neighborly survival. Free buses, public groceries, tenant protections — policies that sounded utopian to elites but felt tangible to Astoria’s rent-burdened households.

The DSA’s strength, as HKS notes, lies in its ability to “transform anger into organizing, and organizing into power.” This was Mamdani’s genius: translating the outrage of rent hikes and wage theft into the cadence of canvassing, into the logistics of voter turnout, into an election-night upset that left New York’s political class scrambling.

1.7 The Outsider Within

Thus, the child of Kampala and Queens becomes the insurgent of Astoria. His origins are not a footnote to his politics; they are its foundation. The outsider within carries rupture as inheritance and rebellion as vocation.

This is why Mamdani’s story matters beyond Astoria, beyond New York, beyond even America. He is not merely an assemblyman on the make. He is a symptom of democracy’s restless evolution, proof that exile can become blueprint, that diaspora can become insurgency, that the outsider within may yet become the architect of a new city.

Part 2: The Bronx Crucible

Inside the Bronx High School of Science — where cricket teams, failed elections, and a taste for resistance foreshadowed his insurgency.

2.1 The Bronx as Paradox

Bronx High School of Science is a palace of intellect built in a borough scarred by disinvestment. Its corridors echo with future Nobel laureates, math prodigies, and debate champions. Yet outside, the Bronx breathes a harsher air: subways thick with neglect, public housing towers bearing the scars of decades of austerity, tenants forever bargaining with landlords.

This paradox — elite excellence within a landscape of inequality — would shape Zohran Mamdani’s adolescent imagination. He absorbed the privileges of an elite school while walking daily through neighborhoods where families faced eviction notices or crowded apartments. It was here, in this crucible, that Mamdani’s insurgent sensibility began to take form.

The Harvard Gazette (2022) warned that “housing policy fuels inequality in America” by determining access not just to shelter but to education, health, and opportunity. The Bronx was a living exhibit of that thesis. Mamdani was fortunate enough to step into Bronx Science’s classrooms, but he could not unsee the ways in which housing instability shaped his peers’ lives beyond those walls.

2.2 Cricket, Campaigns, and Failure

Within Bronx Science, Mamdani gravitated toward two passions: cricket and politics. Cricket was his inheritance from diaspora, a game played in immigrant enclaves more than in American suburbs. He organized, recruited, led — discovering the rhythms of building a team, a precursor to canvassing crews he would one day mobilize in Astoria.

Politics, however, did not come easily. Mamdani ran for student government and lost. And then lost again. These defeats mattered. They inoculated him against the myth of inevitability and taught him resilience. Where others might retreat, Mamdani developed a taste for contest.

Failure, in his case, was not the opposite of politics. It was its apprenticeship. To lose at Bronx Science was to gain the muscle memory for insurgency: persistence after rejection, strategy after setback, voice after silence.

2.3 Housing as Background Radiation

Even if Bronx Science cloaked itself in the aura of meritocracy, the borough reminded Mamdani that inequality was more structural than personal. Families across the Bronx spent disproportionate shares of income on rent. The Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies’ Renters Report 2023 found that half of U.S. renter households were “cost burdened” — spending more than 30 percent of income on housing, with the burden falling hardest on immigrant and working-class families.

By the time Mamdani was navigating student elections, Bronx households were already prototypes of this national crisis. Substandard apartments, doubled-up families, and long waiting lists for public housing etched themselves into his political awareness. The Bronx was not abstract inequality; it was embodied in friends who moved apartments mid-year, in teachers who whispered about students sleeping on couches, in the quiet anxiety of classmates balancing AP courses with household instability.

The State of the Nation’s Housing 2024 report confirms what the Bronx already foreshadowed for Mamdani: housing was becoming the defining inequality of American life.

2.4 The Bronx as Curriculum

To call Bronx Science a school is only half-true. For Mamdani, the Bronx itself was a second curriculum. The subway stations, the housing towers, the grocery stores where EBT cards stretched thin — all of these taught lessons as vivid as textbooks.

The Harvard Law Review (2021) framed this tension starkly: “Housing is not merely a commodity; it is a human right that determines access to citizenship in practice.” For a child of immigrants, watching neighbors live that contradiction — possessing papers but lacking stable shelter — revealed the limits of legal belonging. Citizenship on paper did not equal dignity in life.

Thus, Bronx Science gave Mamdani the vocabulary of excellence, but the Bronx gave him the vocabulary of injustice. The former made him fluent in elite grammar; the latter made him fluent in insurgency.

2.5 Culture as Rehearsal

If Bronx Science was Mamdani’s laboratory of resilience, the Bronx itself offered another stage: culture. Between cricket tournaments and homework, Mamdani experimented with hip-hop — an alter ego that freestyled frustration and ambition in equal measure. These verses foreshadowed the performance politics he would later master: the blending of rhythm, rebellion, and representation into a political art form.

Hip-hop in the Bronx was never merely entertainment. It was protest, memory, and demand. By picking up the mic, Mamdani placed himself inside a lineage of working-class creativity — one that insisted on visibility against erasure. That sensibility would follow him into canvassing scripts and floor speeches: politics as performance, performance as politics.

2.6 The Housing Question

Even as he played with beats and ballots, the shadow of housing loomed larger. New York’s affordability crisis was metastasizing by the early 2000s, and the Bronx felt it acutely. Waiting lists for public housing grew longer, while private rents crept higher. Friends moved mid-semester, teachers whispered about homelessness, and the borough’s inequality widened.

The Harvard Kennedy School (2023), in its report Reimagining Public Housing for Equity, argued that cities must “treat housing as foundational infrastructure, not a residual welfare program.” This principle was already visible in the Bronx’s daily life. Where housing was stable, communities flourished. Where it faltered, everything else collapsed.

Mamdani absorbed this lesson intuitively. Long before he quoted housing policy on campaign flyers, he had witnessed housing instability unraveling lives around him.

2.7 Designing Equity

Housing is not just economics; it is architecture. The Harvard Design Magazine (2020) argued that cities must “design housing as essential infrastructure,” embedding equity into urban form. The Bronx illustrated this vividly. The austere towers of NYCHA public housing stood as both monuments of survival and reminders of neglect. Their design spoke to a mid-century vision of mass shelter, yet decades of disinvestment left them cracked and crumbling.

For Mamdani, these towers became political landmarks. They represented the promise and betrayal of public commitment: proof that the state could house millions, but also warning of what happens when the state retreats. Later, when he championed social housing in Albany, these towers’ silhouettes hovered over his speeches.

Comparative models sharpened this lesson. The Harvard JCHS Social Housing in Comparative Perspective (2023) highlighted Vienna, Singapore, and Berlin — cities where public or cooperative housing systems stabilized affordability. These examples gave Mamdani vocabulary and precedent to argue that New York need not be bound by market fatalism.

2.8 Conclusion: The Crucible Complete

Looking back, Mamdani’s Bronx years resemble the overture to a political symphony. Cricket taught him organization. Failed student campaigns taught him resilience. Hip-hop taught him performance. Housing precarity taught him urgency. Together, they formed the chords of a politics that would later crescendo in Astoria.

The Harvard JCHS (2024) summarized the crisis: “The affordability gap has reached historic levels, disproportionately burdening renters in lower-income and immigrant communities.” Mamdani had seen this not as data but as daily reality. Bronx Science had given him equations and debate formats; the Bronx had given him eviction notices and overcrowded apartments. He emerged fluent in both.

Thus, the Bronx Crucible was not incidental to Mamdani’s insurgency; it was its apprenticeship. It taught him that politics is performance, that failure is rehearsal, and that housing is not an issue but the stage upon which all other issues are performed. The Bronx, in its brilliance and brutality, carved into Mamdani the conviction that democracy must be reimagined from the tenant’s floor up. And in that conviction lies the insurgent path that would carry him from cricket fields and failed campaigns to the corridors of City Hall.

Part 3: Hip-Hop, Housing, and Hustle

From basement beats to tenant battles, Mamdani turned rhythm into rebellion and housing into a manifesto.

3.1 Beats as Apprenticeship

Before Zohran Mamdani was a candidate, he was a performer. In Queens basements and Bronx hangouts, he freestyled under a rap alias — a young man sharpening his tongue on beats, learning how rhythm could bend an audience’s mood. Hip-hop was not just art; it was apprenticeship in insurgency.

The Bronx, birthplace of rap, had already taught him that culture was politics in disguise. Every freestyle was a debate, every cipher a council meeting, every verse a manifesto. Hip-hop insisted that visibility could be wrestled from erasure, that the microphone was a weapon against silence.

This cultural apprenticeship would echo later in his campaigns: rallies that felt like concerts, canvassing scripts that read like rhymes, an insurgent aesthetic that fused grassroots organizing with cultural spectacle. He learned that politics is not only about policies on paper but about presence — about how to make people feel that they matter.

3.2 Housing Hustle: From Counseling to Canvassing

If beats gave Mamdani voice, housing gave him purpose. After college, he took a job as a housing counselor in Queens. Day after day, he sat with tenants navigating eviction threats, rent arrears, and the maze of New York’s housing courts. It was work that combined heartbreak and bureaucracy, activism and clerical grind.

Here, theory turned into grit. Mamdani discovered that inequality was not abstract — it arrived in manila envelopes stamped with “Notice to Vacate.” He watched immigrant families juggle three jobs and still fall behind on rent. He listened as tenants debated whether to buy groceries or pay landlords.

The Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies’ 2023 report on “Location, Mobility, and Housing Affordability” describes this reality in structural terms: where affordable housing is scarce, access to jobs and transit collapses, locking families in cycles of poverty. Mamdani did not need the report to know this; he saw it every week in the faces across his desk.

What he grasped — and what would later define his politics — is that housing is the axis upon which all other injustices spin. Without stable rent, health suffers, education falters, mobility shrinks. The Harvard Gazette warned in 2022 that “housing policy fuels inequality” by reproducing racial and economic segregation. Mamdani’s counseling sessions were that thesis made flesh.

The Hustle as Politics

Counseling alone was not enough. Mamdani began to knock on doors, connecting individual crises to collective action. Here, the hustler’s rhythm met the tenant’s reality. He was not just an advocate; he was a translator, turning the bureaucratic jargon of housing law into plain urgency.

The Bronx had taught him resilience. Hip-hop had taught him cadence. Housing counseling taught him insurgency: the ability to transform private pain into public demand.

This hustle would become his political grammar. Later, as an assemblyman, Mamdani would describe housing as a “human right” and push for statewide tenant protections. The seeds of that platform were planted in these early hustles — in the cramped kitchens of rent-burdened apartments, in the waiting rooms of housing courts, in the late-night phone calls from desperate tenants.

From Rap to Rent to Revolution

Looking back, it is easy to draw the arc: a boy who failed at student politics but rapped to keep his voice alive; a young man who sat in Queens counseling tenants through eviction; a future assemblyman who would build campaigns that sounded more like block parties than policy seminars.

The Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies has called today’s housing crisis “a national emergency,” with half of renters cost-burdened. For Mamdani, the crisis was not a statistic but a rhythm he carried from housing offices to campaign rallies. His politics is born not of spreadsheets but of the hustle: the daily grind of families surviving on the brink, the beat of resistance pulsing through immigrant Queens, the cadence of refusal that insists another city is possible.

3.3 Buses, Mobility, and Insurgent Transit

Housing was Mamdani’s entry point into politics, but transit became his insurgent signature. In Queens, the bus is not a luxury; it is the bloodstream of working-class life. Unlike Manhattan’s subways or Brooklyn’s gentrified bike lanes, Astoria’s arteries are its buses — lumbering, late, crowded, often avoided by the city’s elites but indispensable for its tenants.

It was here that Mamdani saw the tight knot between rent and mobility. Families priced out of central neighborhoods were pushed farther into the peripheries, where rents were marginally lower but buses were the only thread connecting them to jobs, schools, and hospitals. The Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies’ 2023 report on “Location, Mobility, and Housing Affordability” describes this trade-off in stark terms: “Households with limited transit access face compounded costs, as savings in rent are offset by longer commutes and reduced job opportunities.” Mamdani recognized that reality every time he heard a tenant describe two-hour bus commutes across boroughs.

Transit as Inequality’s Mirror

The COVID-19 pandemic sharpened the crisis. As ridership collapsed and subways emptied, buses became the essential vehicles for essential workers. They carried nurses to hospitals, cashiers to supermarkets, delivery drivers across borough lines. The Harvard Kennedy School’s 2022 study on “The future of public transit post-COVID” put it bluntly: “Transit was both lifeline and fault line,” exposing the inequities of who must move and who can afford to stay home.

In Queens, those inequities were daily theater. Middle-class professionals logged in remotely; working-class immigrants packed into buses. The pandemic revealed what had long been obvious to Mamdani: mobility is not neutral. It is stratified by class, race, and geography.

The Harvard Gazette echoed this in 2021, noting that “transportation systems that neglect equity reinforce broader patterns of racial and economic segregation.” For Mamdani, this wasn’t theory — it was the lived truth of Astoria, where a missed bus meant a missed shift, a late rent payment, another eviction notice looming.

The Case for Fare-Free

Mamdani’s boldest proposal — fare-free buses — grew from this crucible. To establishment politicians, it sounded like fantasy. To Astoria’s tenants, it sounded like justice.

The Harvard Kennedy School’s 2024 PolicyCast on fare-free transit outlined the case: eliminating fares not only increases ridership but also reduces inequality, boosts economic access, and reframes mobility as a public good rather than a private purchase. Mamdani seized this argument and translated it into insurgent language: why should billionaires ride helicopters while tenants must scramble for $2.90? Why should the MTA balance its books on the backs of cleaners and home health aides?

The Ash Center’s 2023 report on “Rethinking city buses” offered case studies from Boston, Kansas City, and European cities where fare-free pilots proved transformative. Mamdani drew on these examples to show that Astoria’s demand was not a utopian dream but part of a global movement.

Mobility as a Right

Here Mamdani’s politics aligned with deeper legal and moral frameworks. The Harvard Law Review’s 2022 essay on “Right to Mobility” argued that freedom of movement should be recognized as a civil right, akin to free speech or due process. For Mamdani, buses became the vehicle — literally and figuratively — for advancing this claim. His platform was not simply about saving a few dollars per ride; it was about redefining what democracy owed its people.

The Harvard Design Magazine’s 2020 issue “Cities in Motion” emphasized that transit systems are not neutral infrastructure but “design choices that either reinforce or dismantle inequality.” By advocating fare-free buses, Mamdani positioned himself not as a tinkerer of policy but as a designer of equity, reimagining the city’s circulatory system.

Politics as Performance, Again

Here, the beats returned. When Mamdani spoke about buses, it was not in technocratic jargon. It was in cadences learned from hip-hop: sharp, rhythmic, accessible. He turned transportation equity into a chant, a rallying cry, a chorus repeated at protests and rallies. The microphone of hip-hop became the megaphone of insurgent transit.

The buses themselves became symbols, stage sets for his political theater. Campaign videos filmed on the Q18, rallies at bus stops, hashtags declaring #FreeTheBus — these were not gimmicks. They were performances of belonging, proving that the outsider politician did not just speak about tenants’ lives but lived within them.

Conclusion: From Beats to Buses

Thus, the arc of Mamdani’s early life comes into focus: beats, housing, buses. Hip-hop taught him performance, housing taught him insurgency, buses taught him equity. Together, they formed the hustle that would propel him from tenant counselor to assemblyman, from local insurgent to national symbol.

The Harvard Gazette insists that “transportation is central to equity in cities.” Mamdani insists the same, but in the cadence of insurgency: that a city where tenants cannot move freely is not a democracy but a prison.

From beats to buses, he forged a politics that was not only about survival but about rhythm — the rhythm of movement, of voices rising, of buses rumbling through Astoria not as machines of extraction but as vehicles of dignity.

Part 4: The Rise Against Empire Politics

The 2020 Astoria shock: how a young socialist unseated a four-term Democrat and rewrote Queens’ political grammar.

4.1 The Shock of Insurgency

Astoria in June 2020 was supposed to be predictable. Assemblywoman Aravella Simotas, a four-term Democrat with deep ties to the Queens machine, was expected to glide to re-election. She had the endorsements, the institutional donors, and the quiet confidence of incumbency. But when the ballots were counted, it was Zohran Mamdani — a housing counselor, son of immigrants, and self-proclaimed democratic socialist — who stood victorious.

The upset was seismic. In a district where machine Democrats once ruled unchallenged, an outsider had rewritten the grammar of power. Mamdani didn’t just win a race; he punctured the myth of inevitability. His victory joined a wave — from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the Bronx to Tiffany Cabán in Queens — that declared the borough’s future was no longer in the hands of career politicians but in the fists of organizers, tenants, and workers.

To his supporters, it was more than an election. It was a moment when Astoria itself was redefined: no longer a passive constituency, but a laboratory for insurgent democracy.

4.2 Wages as a Battleground

At the heart of Mamdani’s insurgency was a radical claim: workers deserved not just survival wages, but dignity. While the establishment clung to a minimum wage frozen in political compromise, Mamdani proposed a $30 minimum wage — a number that sounded shocking until tenants explained their rent receipts, childcare costs, and hospital bills.

The Harvard Gazette explored this in 2021, arguing that rethinking the minimum wage is essential to reduce inequality and spur productivity. Their economists found that fears of job loss were often overstated, while wage hikes delivered real gains to the working class. Mamdani translated that into street language: if workers create the wealth of New York, why should they live on scraps?

The Harvard Business Review made the moral and economic case even sharper in its 2020 piece, “Why America Needs a Living Wage.” It argued that low wages are not sustainable even for businesses, eroding productivity and morale. Mamdani’s campaign carried that logic into politics, reframing wages not as charity but as sustainability — for families, for neighborhoods, for the city itself.

Astoria, with its armies of restaurant workers, drivers, and retail clerks, was fertile ground for this argument. In campaign rallies, Mamdani repeated a refrain: survival is not enough. His call for a $30 wage was not utopian; it was rooted in rent bills that devoured half of household incomes. The minimum wage was not an abstraction — it was the thin line between eviction and stability, between food insecurity and survival.

And here Mamdani’s insurgency tapped into the Fight for $15 movement, but pushed it further. If $15 had once sounded radical but quickly became mainstream, why not $30? Why should radicalism be defined by the ceiling of political courage rather than the floor of human dignity?

In this way, wages became Mamdani’s battleground. His victory in 2020 was not just about defeating Simotas, but about introducing a new political vocabulary — one where workers were not afterthoughts but protagonists, where wages were not charity but rights, and where elections were not managed succession but insurgent revolts.

4.3 The Future of Work and Worker Power

Mamdani’s victory unfolded against the backdrop of a labor landscape in upheaval. Automation loomed, wages stagnated, and workers were told to accept precarity as the new normal. Yet in Astoria, the script was being rewritten.

The Harvard Kennedy School’s 2022 report on the “Future of Work in America” laid out the dilemma: as productivity rose, worker wages flatlined, fueling inequality and eroding faith in democracy. Mamdani’s campaign was a direct response to that crisis. He didn’t speak about automation in abstract charts. He spoke about Uber drivers underpaid by an algorithm, about grocery clerks treated as disposable during a pandemic, about tenants balancing two jobs while fearing eviction.

The insurgency he led was not merely electoral. It was cultural, tied to what the Ash Center at HKS in 2023 called “worker power and the new labor movement.” Campaign rallies often resembled labor rallies, where speeches sounded like picket-line chants and supporters spoke less about policy platforms than about dignity. Mamdani’s campaign made clear that the ballot box was an extension of the picket line — and that worker power was democracy’s most authentic muscle.

By channeling this current, Mamdani transformed Astoria’s local race into a referendum on the future of work itself. Should New York be a city of landlords and venture capitalists, or of tenants and workers? His victory suggested the latter had begun to claim its voice.

4.4 The Right to Wages, The Grammar of Democracy

If Mamdani’s campaign was insurgent in tone, it was constitutional in spirit. The Harvard Law Review’s 2022 essay on the “Constitutional Case for a Living Wage” argued that wages are not merely an economic issue but a matter of rights — an extension of the promise of equal protection and substantive liberty. Mamdani embodied that idea on the streets of Astoria. He did not frame wages as a policy adjustment but as a civil demand, inseparable from democracy itself.

The legal logic resonated with tenants who had long understood that survival was political. If freedom of speech was a constitutional right, why not freedom from starvation wages? If the Constitution protected property, why not the dignity of labor that sustained it? Mamdani’s campaign turned these questions into chants, fusing legal analysis with street insurgency.

He also embraced transparency as a democratic weapon. The Harvard Business Review’s 2023 study on pay transparency argued that open wage practices reduce inequality and empower workers. Mamdani called for similar reforms in New York, insisting that secrecy protected exploitation while sunlight redistributed power. For him, wage transparency was not a technocratic tweak but a radical act of democracy — breaking the monopoly of knowledge that employers wielded over workers.

The theme recurred in the Harvard Kennedy School’s PolicyCast (2024), which centered on “the dignity of work and the fight for fair wages.” Scholars there argued that higher wages are not just about poverty alleviation but about affirming that democracy depends on valuing labor. Mamdani’s campaign carried that insight onto Astoria’s doorsteps. He insisted that fair wages were not charity, not compromise, but dignity — and without dignity, democracy itself was hollow.

Conclusion: The Grammar of Insurgency

Thus the 2020 Astoria shock was not only an upset but a rewriting of political grammar. Where machine Democrats spoke in the language of incumbency and compromise, Mamdani spoke in the idiom of rights, dignity, and insurgency. He connected the paycheck to the Constitution, the ballot to the picket line, the rent bill to democracy itself.

In doing so, he redefined what it meant to be a representative in Queens. Not a manager of austerity, but a tribune of workers. Not a negotiator of the status quo, but a challenger of its legitimacy.

The Harvard Gazette had written that raising wages “reshapes inequality and productivity alike.” Mamdani translated that into a demand on the streets: Astoria deserved not survival but dignity, not representation but insurgency. And in 2020, voters agreed.

His victory was not only a rejection of one incumbent but a declaration that the American left’s insurgency had found new grammar — written in the wages of workers, spoken in the voices of tenants, and carried by the son of Kampala and Queens who turned rebellion into representation.

Part 5: The DSA Blueprint

Inside the machine of insurgency: how DSA turned anger into power and tenants into a movement.

5.1 From Anger to Architecture

Movements are often dismissed as moments: sparks that flare, dazzle, and fade. But the Democratic Socialists of America in New York has built something sturdier — an insurgent architecture designed to translate outrage into organization, and organization into power.

When Mamdani ran in 2020, he was not a lone visionary but the product of this architecture. The DSA fielded armies of volunteers who treated canvassing less like campaign work and more like community service. They knocked on doors not only to win votes but to start conversations about rent, wages, and buses. Each interaction was less a pitch than a seminar on democracy.

The Harvard Gazette, in its 2022 commentary on the housing crisis, described the need for “bold solutions equal to the scale of the emergency.” This was precisely the ethos of DSA campaigns: proposals that sounded outrageous to the political class — fare-free buses, social housing, a $30 minimum wage — felt like survival plans to tenants. DSA gave Mamdani a platform where boldness was not a liability but a requirement.

Astoria became the case study of this insurgent architecture. What toppled a four-term incumbent was not charisma alone but structure: the networks of tenants, volunteers, and organizers who turned discontent into discipline. Anger had always existed in Astoria; DSA turned it into a machine.

5.2 Housing as the Core of Socialism

At the heart of Mamdani’s insurgency, and at the center of DSA’s blueprint, is housing. The fight for shelter is the fight that threads together tenants, workers, immigrants, and the precarious middle class. In New York, where rent eats half of many households’ income, socialism finds its most visceral expression not in theory but in leases and eviction notices.

The Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies’ State of the Nation’s Housing 2024 underscored the urgency: affordability has collapsed to historic lows, supply shortages persist, and homelessness is rising. What the JCHS laid out in data, Mamdani framed in politics: a city where landlords dictate life is a city without democracy.

The Harvard Kennedy School’s 2023 analysis of housing policy and inequality sharpened the point. Zoning laws and market dynamics, it argued, perpetuate racial and class divides across U.S. cities. Mamdani translated that into insurgent language: segregation is not an accident of markets but a choice of policy — a choice that can be unmade. His call for statewide tenant protections and social housing was thus not a deviation from mainstream politics but an attempt to expose its deepest contradictions.

Evictions, too, became central to his rhetoric. The Harvard Law Review’s 2021 essay on eviction, race, and structural inequality framed eviction as a civil rights issue — disproportionately targeting Black and immigrant families, cementing cycles of poverty. Mamdani’s years as a housing counselor had already given him this perspective: eviction was not just housing policy, it was racial injustice codified in courtrooms. Every tenant who lost their home was a citizen stripped of dignity.

This framing explains why Mamdani’s socialism resonates beyond the traditional left. When he speaks about housing, he is not offering abstract ideology. He is naming the crisis that shapes everyday life. His socialism is not about theory in manifestos; it is about whether Astoria families can pay rent next month.

In this sense, housing becomes the Rosetta Stone of his politics. It translates global critiques of capitalism into local urgency. It binds tenants and workers into a collective subject. And it gives insurgency its clearest moral clarity: a city where people cannot afford to live is not a city worth defending.

5.3 Social Housing as Infrastructure

For decades, American politics has treated housing as a private commodity — a prize for investors, a dream for homeowners, a precarious rental for everyone else. But Mamdani, drawing on the Democratic Socialists of America’s platform, advances a different vision: housing as infrastructure, housing as a right, housing as the backbone of democracy.

The Harvard Kennedy School’s Ash Center (2023) makes this argument explicitly: “Social housing should be treated as public infrastructure, akin to transit, water, and electricity.” That framing is the intellectual scaffolding of Mamdani’s campaign. If a city can guarantee electricity to every apartment, why not affordable shelter? If buses and bridges are funded as collective goods, why not housing towers designed for tenants rather than investors?

This vision is not utopian. It is comparative. The Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies has shown, in its global research, that European cities such as Vienna and Helsinki have sustained affordability through robust social housing sectors. Mamdani invokes these examples not to romanticize Europe but to puncture American fatalism. If Vienna can house half its population in publicly owned or subsidized units, why can’t New York?

The Clash with Market Logic

The confrontation is clear: socialism’s demand for housing as a public good collides with capitalism’s treatment of housing as an asset class. The Harvard Business Review (2020) probed this contradiction in “Can Affordable Housing Be Profitable?” — a question that exposes the absurdity of relying on markets to solve a crisis they profit from. The report highlighted innovative financing models, but even there, profit was treated as the prerequisite for equity.

Mamdani flips the premise. His DSA blueprint does not ask how affordability can be profitable. It asks how a city can call itself democratic if profitability dictates who gets to live in it. For him, the answer is simple: housing must be decoupled from profit, just as public schools are decoupled from tuition markets.

This is where DSA’s radicalism becomes pragmatic. By pushing social housing as infrastructure, they shift the debate from “can the market solve it?” to “can the state be compelled to act?”

Rental Realities

The Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies’ America’s Rental Housing 2022 report showed that half of renter households nationwide spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent, with a growing share spending over 50 percent. These “severely cost-burdened” households are concentrated in immigrant-heavy, working-class neighborhoods — Astoria among them.

Mamdani did not need the report; he lived it through his housing counseling. But the data reinforced the scale of the crisis: America’s rental market is not broken, it is functioning exactly as designed — to extract maximum value from tenants while insulating landlords and developers.

His solution, rooted in DSA’s platform, was to move beyond subsidies and vouchers. Instead, he called for the state to directly build, own, and manage housing — not as a safety net but as the default. This is the crux of the social housing model: take shelter out of the realm of speculation and place it in the domain of rights.

Housing as the New Common Sense

The Harvard Gazette (2022) declared that “the housing crisis demands bold solutions.” Mamdani turned that faculty commentary into campaign praxis. His insurgent blueprint reframes what once seemed radical — rent control, eviction protections, publicly owned housing — as common sense for a city drowning in inequality.

In speeches, he makes the argument visceral. When Wall Street speculators buy Astoria apartments as investment vehicles, tenants are not merely priced out — democracy itself is eroded, because representation cannot survive when constituents are displaced. Housing, then, is not only about affordability; it is about sovereignty, belonging, and the legitimacy of the political system.

The DSA blueprint embodies this recognition. Housing is not one issue among many; it is the ground upon which all other issues stand. Without shelter, wages lose meaning, healthcare is unstable, education is interrupted. Housing is not policy detail — it is democratic infrastructure.

Conclusion: From Anger to Blueprint

The rise of Mamdani cannot be explained by charisma alone. It is the product of an insurgent machine — the Democratic Socialists of America — and a blueprint centered on the most urgent crisis of urban life: housing.

The Harvard reports confirm what tenants in Astoria already knew: affordability has collapsed, inequality is entrenched, eviction is a civil rights violation, and bold solutions are the only solutions. Mamdani translates that data into politics, turning crises into chants, reports into rallies, analysis into insurgency.

The DSA blueprint is thus not just an electoral strategy. It is a reimagining of what infrastructure means in the 21st century. For Mamdani and his comrades, housing is no longer a commodity. It is the stage on which democracy itself is built.

Part 6: Cuomo’s Fall, Mamdani’s Surge

How the prince of Albany crumbled before the insurgent from Astoria — the upset that stunned America’s political class.

6.1 The Empire Cracks

For more than a decade, Andrew Cuomo ruled Albany like a monarch. He was the “prince of power” — ruthless, calculating, a master of patronage and intimidation. His grip on New York politics seemed unshakable. Legislators feared him. Donors courted him. National pundits whispered about a presidential run.

And then, in a cascade of scandal, the empire cracked.

Cuomo’s carefully constructed image — the tough but steady hand guiding New York through crises — collapsed under the weight of corruption investigations, sexual harassment allegations, and a damning cover-up of nursing home deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. Each revelation stripped him of legitimacy, until even his allies abandoned him.

Albany’s strongman fell not with a bang but a series of humiliations, resigning in 2021 after impeachment seemed inevitable. The man who had epitomized machine politics was reduced to a cautionary tale.

But history is not just about decline; it is about succession. As Cuomo’s empire crumbled, insurgents were rising. And in Astoria, Zohran Mamdani — housing counselor turned assemblyman — embodied the opposite of Cuomo’s politics. Where Cuomo ruled by fear, Mamdani organized by trust. Where Cuomo courted developers, Mamdani rallied tenants. Where Cuomo built highways of patronage, Mamdani charted bus routes of justice.

6.2 Astoria vs. Albany

The clash was never direct — Cuomo and Mamdani did not battle on the same ballot. But symbolically, their trajectories were intertwined: the decline of Albany’s empire politics mirrored the ascent of Astoria’s insurgent grammar.

Cuomo’s politics was transactional. His infrastructure legacy tilted toward vanity projects: airports rebranded with his imprimatur, bridges named for his father, expansions that served developers more than commuters. His administration’s transportation priorities were car-centric, growth-oriented, designed to please donors.

Mamdani, by contrast, represented what the Harvard Gazette (2023) diagnosed in its analysis of U.S. transit inequality: the recognition that “transportation policy too often deepens inequality when designed around cars and capital.” In Astoria, Mamdani pushed the opposite vision: buses for tenants, not bridges for billionaires.

His grassroots insurgency looked nothing like Albany’s patronage machine. Campaigns resembled neighborhood assemblies more than political fundraisers. Volunteers were fueled not by lobbyist dollars but by conviction and cold pizza. In every way, Mamdani’s rise dramatized a transfer of legitimacy: from the transactional elite to the insurgent grassroots.

Astoria was Albany’s counter-narrative. And Mamdani was Cuomo’s foil.

6.3 Transit as Counter-Empire

If Cuomo’s empire was defined by monumental infrastructure, Mamdani’s insurgency was defined by the humble city bus.

Buses are not glamorous. They do not inspire ribbon-cuttings or international headlines. But they are lifelines — especially in immigrant-heavy districts like Astoria, where workers depend on them to reach jobs scattered across the boroughs. For Mamdani, fare-free buses became the perfect emblem of insurgent politics: small in cost compared to Cuomo’s megaprojects, massive in democratic meaning.

The Harvard Gazette (2022) profiled Boston’s free-bus experiment, noting that “ridership surged among low-income riders, travel times improved, and households gained disposable income.” What Boston tested, Mamdani demanded: scale it up, make it permanent, treat it as infrastructure, not charity.

The Harvard Law Review (2021) offered the legal framework, insisting that “transit justice is inseparable from the right to mobility,” and that exclusion from public transit should be understood as a civil rights violation. Mamdani seized this argument and carried it into the New York Assembly. A bus ticket, he declared, was not a consumer product but a democratic right.

This argument was insurgent not because it was radical in numbers — the cost of fare-free buses is marginal in the state’s budget — but because it inverted the hierarchy of priorities. Cuomo’s New York invested billions in projects that flattered elites. Mamdani’s New York would invest millions in buses that dignified the working class.

Here, transit became counter-empire. Every fare-free bus was a quiet rebellion against Albany’s extravagance, a moving billboard for equity. Where Cuomo’s bridges symbolized dynastic legacy, Mamdani’s buses symbolized insurgent democracy.

And the symbolism worked. Riders who boarded Mamdani’s campaign buses — often rallies staged at stops, with volunteers handing out literature like transfers — did not see abstract policy. They saw themselves, their dignity, their right to move without penalty.

6.4 Climate, Transit, and the Future

Cuomo liked to present himself as a builder — bridges, airports, gleaming ribbon-cuttings under floodlights. But while he celebrated concrete and steel, climate reality pressed against New York’s foundations. Superstorm Sandy had already devastated the city in 2012, flooding subways and crippling infrastructure. Rising seas threatened neighborhoods from the Rockaways to Red Hook.

Yet Cuomo’s climate politics were wrapped in contradictions: lofty speeches paired with highway expansion, renewable goals undermined by fossil fuel lobbying. His empire politics operated on spectacle; resilience was an afterthought.

Mamdani entered with a different script. For him, transit was not only about equity but about climate justice. The Harvard Kennedy School’s 2023 report, “Rethinking Urban Transit for Equity and Climate,” argued that fare-free transit can simultaneously cut emissions and expand access, especially for low-income riders. Mamdani translated that into plain urgency: every fare-free bus was a small decarbonization policy wrapped in a dignity policy.

The Ash Center (2024) sharpened the argument, describing public transit as “central to climate resilience.” Mamdani made the connection explicit: the same buses that carried tenants to work could also carry the city into survival. In campaign speeches, he fused class struggle with climate adaptation: “The bus is not just how we move today. It’s how we decide if we have a tomorrow.”

This was insurgency reframed: not merely opposition to Albany’s corruption, but a proactive claim that climate and class were one struggle — and that a fare-free bus was a frontline weapon in both.

6.5 Designing Mobility for Democracy

Transit was also about design — not in the architectural sense, but in the political. The Harvard Business Review (2020) explored “designing sustainable and inclusive mobility systems,” highlighting public–private partnerships as ways to innovate. Mamdani was skeptical. For him, privatization was the infection, not the cure. Mobility, like housing, had to be decommodified.

Yet he did not ignore innovation. He looked to the Taubman Center’s 2024 “Urban Mobility Futures” paper, which debated congestion pricing, electrification, and expanded transit funding. Where others framed these as traffic-management tools, Mamdani reframed them as democracy tools. Congestion pricing wasn’t just about unclogging Midtown; it was about redistributing resources toward neighborhoods where tenants relied on buses. Electrification wasn’t just climate adaptation; it was labor dignity, ensuring frontline communities breathed cleaner air.

Here Mamdani insisted that transit was not technocracy but democracy. Policy details were not neutral; they were questions of power. Who pays for the subway? Who profits from congestion pricing? Who decides where the next bus route goes? In Albany, these questions were often answered in closed rooms with lobbyists. In Astoria, Mamdani made them campaign chants.

By doing so, he transformed policy debate into insurgent theater — insisting that democracy begins at the bus stop.

6.6 The Surge of Insurgency

As Cuomo’s career imploded, Mamdani’s profile surged. He was no longer just Astoria’s assemblyman; he became a symbol of the legitimacy shift sweeping New York politics. Cuomo’s empire politics — centralized, donor-driven, car-centric — was exposed as brittle. Mamdani’s insurgency — decentralized, volunteer-powered, bus-centric — revealed itself as resilient.

Transit justice became shorthand for political justice. A fare-free bus in Astoria stood not just for cheaper commutes but for a new kind of politics: participatory, equitable, unafraid of the word socialism.

The Harvard Gazette (2022) had observed that fare-free buses “boost equity while restoring trust in public systems.” Mamdani made that observation a movement. Trust, in his model, was not won through empire-style dominance but through insurgent solidarity. Every canvass, every rally, every free bus pilot became a rehearsal for a new democracy.

The contrast could not have been starker. Cuomo left office as a disgraced relic of old New York, remembered more for scandal than substance. Mamdani rose as the face of a restless left, carrying the grammar of insurgency from Astoria stoops to the halls of Albany.

In this way, Mamdani’s surge was not simply the mirror of Cuomo’s fall. It was its successor. The vacuum left by empire politics was filled by bus politics — small, unglamorous, but profound in its redefinition of power.

The empire cracked, and through the fissure, insurgency surged. From Astoria to Albany, from buses to climate, from tenants to workers, the path forward was no longer carved by princes of power but by insurgents of justice.

Part 7: The People’s Manifesto

A forensic dive into Mamdani’s platform: fare-free buses, public groceries, $30 minimum wage — utopian dreams or practical blueprints?

7.1 Utopian or Practical?

When Zohran Mamdani unfurls his platform — fare-free buses, public groceries, a $30 minimum wage, universal health care — critics dismiss it as utopian theater. Albany insiders whisper that his proposals are impossible in a state budget already strained by pensions and infrastructure debt. Pundits call them slogans, not policy.

But in Astoria, Mamdani’s district, these policies don’t read like dreams. They read like survival plans. For tenants living paycheck to paycheck, a fare-free bus isn’t an abstraction — it’s the difference between buying groceries and skipping dinner. For cashiers making $15 an hour while rents swallow half their income, a $30 wage is not an ideological indulgence but the minimum for dignity. For families juggling bills and medical debt, universal health care is not a socialist fantasy, but the only rational option left.

The Harvard Gazette warned in 2020 that inequality “literally shortens lifespans,” documenting how income and race map onto health outcomes. In New York, that inequality is brutal. A child born in the Upper East Side can expect to live a decade longer than a child born in the Bronx. Against such disparities, moderation looks less like prudence than negligence.

Mamdani insists that the true utopia is believing the current system can continue. The “radical” position, he argues, is not fare-free buses or public groceries, but the fiction that people can survive on $15 wages while landlords and insurers extract more each year. His manifesto, far from being an ideological indulgence, is an attempt to make democracy functional for those long excluded from it.

7.2 Health as a Human Right

If housing and transit have defined Mamdani’s insurgency, health care has become its moral center. He argues, simply, that no democracy can survive while millions live one medical bill away from ruin.

Here he joins a chorus of scholars who insist that health is not a privilege but a right. The Harvard Gazette (2022) featured faculty declaring that “health care is a human right, not a privilege,” noting that the U.S. is the only wealthy democracy that treats care as a market commodity. Mamdani translates that indictment into insurgent cadence: “If we can guarantee the right to property in this country, why can’t we guarantee the right to health?”

The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (2023) sharpened the policy case in “The Case for Universal Health Coverage.” Universal systems, it argued, are not only more just but also more efficient, eliminating administrative waste and ensuring equitable access. Mamdani draws from this pragmatism. His call for universal care is not couched in utopian rhetoric but in fiscal realism: the United States spends more per capita on health than any other nation yet delivers worse outcomes. Efficiency and equity, in this case, are not opposites but allies.

COVID-19 made this case visceral. In Astoria, the pandemic tore through immigrant households, exposing the inequities in testing, treatment, and vaccination access. The Harvard Global Health Institute (2021) emphasized that COVID revealed “structural inequalities baked into the health system” and argued for redesign based on equity. Mamdani didn’t need the report; he saw it on the ground. But the scholarship reinforced his conviction: the crisis was not only viral but structural, and survival demanded systemic reform.

At rallies, Mamdani reframes universal health care not as a luxury but as a baseline. He reminds supporters that even in New York, one of the wealthiest cities on earth, tens of thousands lack insurance. He links this directly to mortality disparities: Black and Latino New Yorkers die younger, not because of biology, but because of a system that rations care by income.

This framing turns health care into a litmus test for democracy. If life expectancy depends on zip code, Mamdani argues, then democracy has failed. His manifesto transforms the moral imperative of care into political architecture: public clinics, universal coverage, dignity-first delivery.

And for his supporters, this isn’t abstract ideology. It is the demand that their democracy extend beyond the ballot box into the doctor’s office, the pharmacy, the emergency room.

7.3 Health Justice as Structural Reform

To Mamdani, universal coverage is the floor, not the ceiling. His manifesto insists that justice requires dismantling the structural inequities that shape health itself.

The Harvard Law Review (2021) argued that U.S. health systems “perpetuate inequality by embedding discrimination in access, financing, and delivery.” This is what Mamdani translates into politics: a clinic system where immigrants hesitate to seek care for fear of bills or deportation, a hospital network where zip code dictates survival rates, a labor market where low wages mean untreated illnesses.

The Harvard Kennedy School (2023) expanded the frame, calling for “redesigning public health infrastructure” around prevention, dignity, and integration. Mamdani echoes this vision in his platform for neighborhood-based clinics and state-backed care. His blueprint seeks to turn health infrastructure from profit centers into public goods, a transformation as radical — and as pragmatic — as electrifying buses or expanding rent control.

The Harvard Medical School (2024) added a cultural dimension, emphasizing “community health and dignity in care.” Mamdani’s speeches resonate with this ethos. For him, health policy is not just about insurance; it’s about respect. When tenants describe hours-long waits in overcrowded ERs, they are not just recounting inefficiency — they are describing humiliation. The manifesto turns this indignity into a rallying cry: care must be reimagined as recognition, not rationing.

Thus, health justice becomes structural justice. It is not a single reform but a reordering of priorities, moving from profit to dignity, from exclusion to belonging.

7.4 The Platform as Insurgency

Health care anchors the manifesto, but it is not alone. Each plank — fare-free buses, public groceries, a $30 minimum wage — is part of the same insurgent grammar.

Fare-free buses, already tested in Boston, are more than transport. They are health policy (cutting stress and improving access), climate policy (reducing emissions), and equity policy rolled into one. The Harvard Gazette (2022) reported that free bus pilots increased ridership and improved outcomes for low-income riders. Mamdani takes this as proof that what skeptics call “utopian” is already pragmatic.

Public groceries, one of his boldest ideas, embody the same logic. If food insecurity is endemic — with immigrant families skipping meals to make rent — then food must be treated as infrastructure. Here Mamdani applies the principle of social housing to nutrition: de-commodify the essentials. Critics deride it as socialism; tenants call it survival.

And the $30 minimum wage ties the manifesto together. It is not only about income; it is about health, education, and life expectancy. The Harvard Gazette (2020) showed that inequality literally shortens lives. A higher wage is therefore not an economic adjustment but a public health intervention. Mamdani reframes wages as medicine: pay people fairly, and you extend lifespans.

In this way, the manifesto operates as insurgency. It takes policies the establishment dismisses as impractical and redefines them as necessary. It refuses to separate economics from health, climate from dignity, survival from democracy.

7.5 The Grammar of Dignity

What unites the manifesto is not ideology but dignity. Each proposal — whether buses, groceries, wages, or clinics — flows from the same premise: democracy without dignity is a shell.

The Harvard Medical School’s 2024 emphasis on dignity-first care provides the intellectual echo. Mamdani makes it visceral. He speaks not in think-tank jargon but in neighborhood cadence: “Why should a billion-dollar city leave its people hungry? Why should a city of skyscrapers evict families into shelters?”

The grammar is insurgent but also poetic. His manifesto reads like scripture for the working class, blending policy architecture with the rhythm of refusal. It is technocratic in detail but literary in style — the $30 wage alongside the language of survival, the public grocery alongside the poetry of belonging.

And perhaps that is why the manifesto terrifies the establishment. It refuses to be dismissed as dream because it is too rooted in reality. It refuses to be dismissed as impractical because it cites both Harvard research and Astoria’s rent bills. It fuses the authority of scholarship with the authenticity of lived experience.

In the end, The People’s Manifesto is not a utopian wishlist. It is a mirror, reflecting the crises of New York — housing, wages, health, food, transit — and demanding that democracy rise to meet them. In Mamdani’s hands, it becomes both blueprint and insurgency, policy and performance, data and dignity.

The manifesto, then, is not about Zohran Mamdani alone. It is about the unfinished work of American democracy. And it insists, with the clarity of both scholarship and struggle: survival is not enough. Dignity must be the floor.

Britain & Nigeria’s Conspiracy To Silence Kanu

Part 8: Empire City vs. Social City

Wall Street panic, grassroots euphoria: how New York’s billionaires and tenants are reading the Mamdani moment.

8.1 Panic in the Towers

In Midtown Manhattan, the towers gleam like monuments to permanence. Hedge funds perch high above the streets, and real estate executives measure the city’s health not by eviction rates but by stock performance. For these stewards of Empire City, the name Zohran Mamdani is spoken less as a politician than as a threat.

Mamdani’s housing-centered politics unsettles them precisely because it aims at the foundations of their wealth. Wall Street treats housing as an asset class — apartments as investment vehicles, luxury towers as safe havens for global capital. For Mamdani, housing is not an asset but a right. That inversion is existential.

The Harvard Gazette (2022) described the U.S. affordability crisis as rooted in “a speculative market detached from the needs of residents and a failure to expand social housing.” That sentence reads like a gloss on Mamdani’s campaign speeches. He argues that New York has become an empire city: a landscape sculpted for investors, not for its own people.

Inside boardrooms, this insurgency is treated with alarm. If tenants can organize at the ballot box, if housing is reframed as infrastructure, then profit margins evaporate. For financiers, Mamdani represents not just a candidate but a contagion: the idea that New York could be governed by tenants instead of titans.

8.2 Tenants’ Revolt

If Wall Street sees a contagion, Astoria sees a revolution. For tenants long ignored by Albany and City Hall, Mamdani’s insurgency feels like representation for the first time in decades. Campaign rallies are less political events than neighborhood assemblies — tenants swapping eviction stories, immigrants comparing rent hikes, activists distributing flyers that read like survival manuals.

The Harvard Law Review (2021) framed tenants’ rights as “a constitutional and moral imperative in the 21st century,” linking rent justice to broader democratic legitimacy. Mamdani echoes this analysis on Astoria’s streets: “If the Constitution protects property, why doesn’t it protect the people who live in it?”

The joy among tenants is not abstract. It is embodied. Elderly renters who remember the old rent-control battles of the 1970s now see echoes of that struggle in Mamdani’s platform. Younger tenants, raised in an era of precarious leases and sudden evictions, discover solidarity in collective refusal.

The Harvard Gazette (2021) called eviction a “public health crisis,” connecting instability to mental illness, poor health outcomes, and shortened lifespans. Mamdani weaves this into insurgent cadence: eviction is not only a housing issue but a survival issue. To fight for tenants is to fight for health, dignity, and democracy all at once.

The revolt, then, is not only about policy. It is about belonging. For tenants who have long felt disposable in a city of billionaires, Mamdani’s rise is a collective vindication: their lives, their homes, their struggles matter.

8.3 Data vs. Lived Crisis

In the halls of Harvard, the crisis is captured in charts and tables. The Joint Center for Housing Studies’ State of the Nation’s Housing 2024 report warns that affordability has collapsed to “historic lows,” with rent burdens rising across all income groups. Its 2022 America’s Rental Housing study documented eviction trends and the widening affordability gap, noting that nearly half of renter households are cost-burdened.

For Mamdani, those statistics are not sterile. They are the arithmetic of Astoria kitchens. He translates percentages into parables: a tenant choosing between insulin and rent, a family doubling up in a one-bedroom apartment, a cashier whose wage increases are devoured by rising rents.

The reports confirm what Astoria has long known: the market is functioning exactly as designed — to enrich investors and dispossess tenants. But where think tanks conclude with policy recommendations, Mamdani concludes with insurgency. His politics transforms data into demand.

He tells supporters that Wall Street has its reports; tenants have their receipts. The former charts trends; the latter proves theft. And between the two lies the battlefield: will New York remain an empire city, organized around speculative capital, or become a social city, organized around human need?

8.4 Designing a Social City

If Empire City is designed for investors, Mamdani’s insurgency asks: what would a city designed for tenants look like?

He begins with rent stabilization, eviction protections, and the radical notion that housing should be governed as infrastructure, not speculation. The Harvard Kennedy School (2023) offered a similar blueprint, arguing that “designing housing policy for equity requires expanding rent stabilization and building new models of social housing.” Mamdani translated that prescription into political rhythm: freeze the rents, build the homes, return the city to its people.

The Ash Center (2020) profiled innovations in affordable housing, from rent freezes in Berlin to city-led social housing programs in Vienna and Helsinki. These international models fuel Mamdani’s argument that New York is not condemned to austerity. Other cities, equally global and capitalist, have built public housing that anchors democracy rather than undermines it.

The Harvard Gazette (2022) had already warned that America’s affordability crisis was “the predictable outcome of policy choices that subsidized speculation while starving social housing.” Mamdani reframes this as indictment: Albany and City Hall didn’t fail tenants accidentally; they succeeded in serving landlords. His insurgency insists that success must be measured differently — in evictions prevented, rents stabilized, lives dignified.

In this vision, the “social city” is not utopia but necessity. It is built from the recognition that democracy cannot stand on a foundation of displacement.

8.5 Empire vs. Socialism as Identity

At its core, the clash between Mamdani’s vision and Wall Street’s panic is not just policy — it is identity.

Empire City is defined by its skyline: towers of glass designed for global investors, apartments purchased but left empty as financial instruments. Its politics is donor-driven, its legitimacy measured in bond ratings and development deals. In Empire City, tenants are temporary; capital is permanent.

The Harvard Law Review (2021) traced this logic to the legal order itself, noting that “tenants’ rights remain fragile while property rights are sacrosanct.” Mamdani seizes that imbalance as the very definition of Empire City: a place where property has citizenship but people do not.

Social City, by contrast, is defined by belonging. It treats housing as infrastructure, eviction as a civil rights violation, and dignity as non-negotiable. The Harvard Gazette (2021) declared eviction a “public health crisis,” linking instability to illness, despair, and shortened lifespans. Mamdani builds on this truth: Empire City shortens lives, Social City extends them.

Data from the JCHS State of the Nation’s Housing 2024 provides the statistical backbone. Nearly half of renters are cost-burdened; millions face eviction risk each year. For Mamdani, this is not a housing crisis but a democratic crisis. Socialism, in his telling, is not ideology but identity: the only way for New York to remain livable for its people rather than a playground for global finance.

The America’s Rental Housing 2022 report described the “deepening rent burden as systemic, not cyclical.” Mamdani translates that into insurgent poetry: “This isn’t a cycle. It’s a system. And we’re here to break it.”

So the choice becomes stark. Empire City or Social City. A skyline owned by investors or a neighborhood owned by tenants. Democracy as speculation or democracy as survival.

Mamdani’s insurgency insists that the city must choose — and in that choice lies the future not only of New York, but of the American left itself.

Conclusion: The Battle for the City

Thus, Part 8 closes where it began: with panic in the towers and euphoria in the tenements. Wall Street fears Mamdani because he makes visible what was supposed to remain invisible: that the empire of glass towers rests on the dispossession of millions. Tenants celebrate him because he turns their survival into political scripture.

The Harvard Kennedy School, JCHS, and Law Review provide the academic scaffolding. Mamdani provides the insurgent grammar. Together, they sketch two visions of New York: Empire City, ruled by capital, and Social City, claimed by tenants.

And in that clash — between profit and dignity, speculation and solidarity — the insurgent from Astoria has found not only his platform but his purpose.

Part 9: The Internationalist Mayor

From Palestine to Modi: Mamdani’s unapologetically global politics — and how foreign policy haunts New York streets.

9.1 Diaspora as Destiny

Zohran Mamdani was never going to be a parochial politician. His very biography refuses borders. Born in Uganda, of Indian heritage, raised in Queens — his identity embodies displacement, empire, and migration all at once. For him, politics was never simply local; it was always global, because his life was evidence of how global violence shapes local existence.

New York is the city of diasporas, where conflicts in Kashmir, Gaza, or Kampala find expression in Jackson Heights parades or Astoria block meetings. Most politicians treat this as a minefield — too dangerous, too polarizing. Mamdani treats it as reality. He insists that to represent Astoria honestly is to acknowledge its global entanglements.

His politics, then, is less about exporting ideology abroad and more about recognizing that the world already resides in Queens. The immigrant who struggles to pay rent in Astoria is often the same immigrant who sends remittances back to families shaped by neoliberal reforms, climate change, or authoritarian regimes. The global is not elsewhere. It is here.

This is why Mamdani can never be just a neighborhood assemblyman. He is, in effect, a diasporic tribune, carrying into Albany the unresolved contradictions of empire, displacement, and global capitalism.

9.2 Palestine in Queens

Nothing illustrates Mamdani’s internationalism more starkly than his unapologetic advocacy for Palestine. In Albany, state legislators are rarely expected to comment on foreign policy. But Mamdani refuses that division. For him, Palestine is not a foreign issue. It is a local one.

Queens is home to thousands of Arab and Muslim immigrants, many of whom carry memories of occupation and dispossession. Their struggles do not vanish at JFK Airport; they reappear in Astoria’s streets, in tenant unions, in Friday prayers. By speaking for Palestine, Mamdani speaks for constituents who have long been told their pain is irrelevant to American politics.

The backlash has been fierce. Pro-Israel lobbies have attacked him, establishment Democrats have distanced themselves, and editorial boards have accused him of distraction. But the grassroots response has been the opposite: rallies filled with Palestinian flags alongside DSA banners, chants for tenant justice interwoven with calls for free Palestine.

For Mamdani, the issue is not whether foreign policy belongs in state politics but whether his constituents belong in democracy. If they carry Palestine in their hearts, then silence would be abandonment.

In this sense, Palestine becomes a mirror of his broader insurgency. Just as he reframes buses as rights, not services, he reframes foreign solidarity as democracy, not distraction. His politics insists that justice cannot be partitioned: to fight for tenants in Astoria while ignoring occupation abroad is to fragment the very meaning of solidarity.

9.3 Modi, Hindu Nationalism, and the South Asian Left

If Palestine tests the boundaries of foreign policy in Albany, Mamdani’s critique of Narendra Modi tests the politics of South Asian diaspora in Queens.

New York’s Indian community is fractured. Many immigrants celebrate Modi’s rise as a triumph of national pride, a long-overdue assertion of Hindu majority power. Others, especially younger progressives, view Modi as an authoritarian who has weaponized religion to marginalize Muslims, Dalits, and dissenters.

Mamdani has taken a clear stand. He denounces Modi’s Hindu nationalism as part of a global authoritarian trend — kin to Trumpism, Bolsonaro, and Orbán. His position is risky: Hindu nationalists in Queens are organized, wealthy, and politically connected. But Mamdani’s insurgency thrives on naming the fault lines others avoid.

His critique resonates especially among Muslim, Sikh, and leftist South Asians who see Modi’s India as a betrayal of pluralism. In rallies, Mamdani frames his opposition to Modi not as foreign commentary but as local solidarity: Astoria’s South Asians are living the consequences of Hindu nationalism through family ties, remittances, and political identities shaped abroad.

This is where Mamdani’s internationalism differs from cosmopolitanism. It is not about celebrating diversity but about confronting power. He does not frame Modi as distant, but as proximate: the ideology shaping Delhi is shaping Jackson Heights too.

In this way, Mamdani links Queens’ South Asian politics to a global left struggle. His Astoria insurgency is simultaneously a resistance against landlords at home and strongmen abroad.

9.4 Wages Without Borders