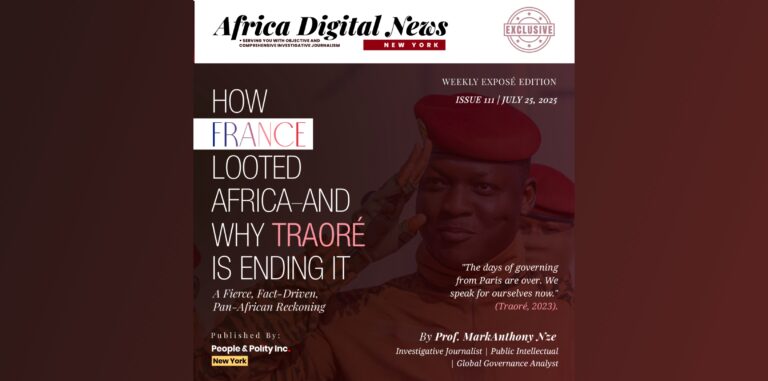

A Fierce, Fact-Driven, Pan-African Reckoning

“The days of governing from Paris are over. We speak for ourselves now.”

(Traoré, 2023).

By Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Investigative Journalist | Public Intellectual | Global Governance Analyst

Executive Summary

This report offers a masterfully detailed exposition of France’s evolving and increasingly challenged role in Africa, revealing the layers of neocolonial legacy, strategic manipulation, economic exploitation, and the continent’s growing resistance, particularly through the assertive emergence of new leaders like Captain Ibrahim Traoré. Over twelve rigorously structured sections, the analysis unpacks the decline of Francafrique—France’s post-independence network of influence in its former colonies—and maps the resurgence of African agency, sovereignty, and unity in the 21st century.

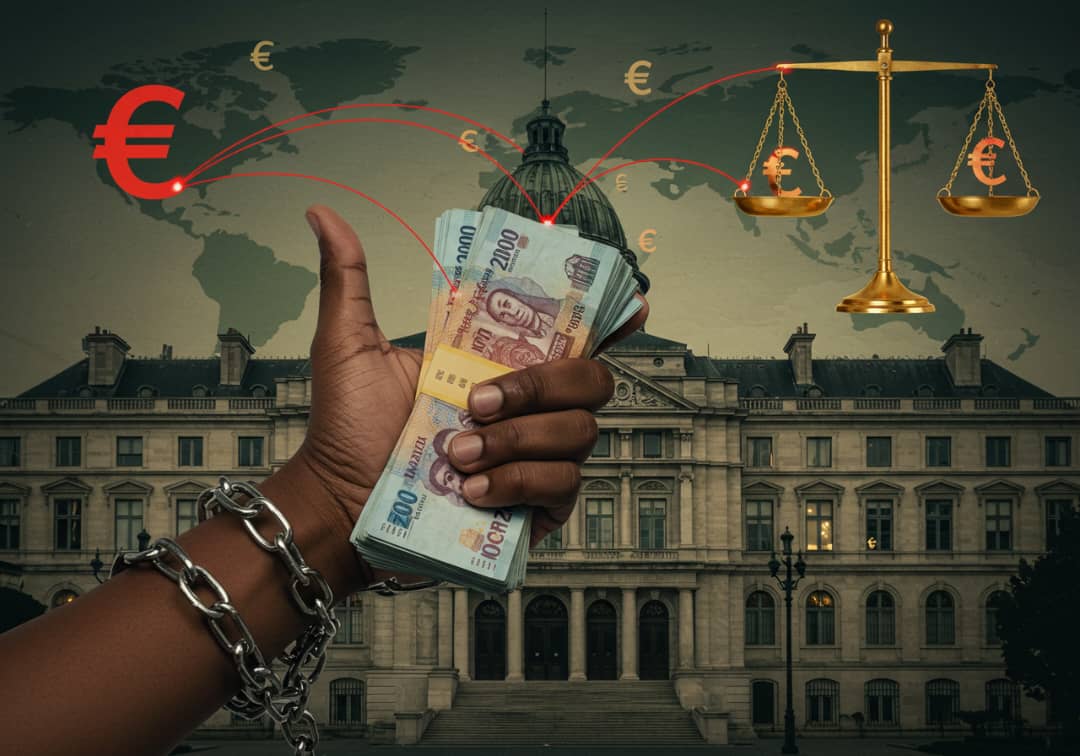

The document begins by exposing how France entrenched its dominance through monetary and institutional means. Chief among these is the CFA franc—a currency system that, under the guise of stability, has long functioned as a tool of French economic hegemony. Through direct control of African reserves and influence over regional central banks, France ensured its continued sway over monetary policy in West and Central Africa. Despite formal independence, this arrangement structurally limited economic autonomy, leaving Francophone nations tied to a colonial-era financial umbilical cord.

This monetary grip was matched by military entrenchment. The report scrutinizes France’s deep military footprint, particularly through Operation Barkhane and other Sahel deployments. Originally justified as counterterrorism initiatives, these missions gradually lost legitimacy amid growing public suspicion and evidence that they protected French interests—especially extractive industries and regional leverage—rather than enhancing African security. Massive protests and civil unrest eventually led to the expulsion of French troops from countries such as Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, signaling a seismic collapse of French hard power in the region.

At the heart of this unraveling are the extractive and corporate interests that underpin France’s involvement. The report provides a compelling account of how multinationals like TotalEnergies and Bolloré have dominated key sectors—from oil to logistics to port management—reaping vast profits while contributing minimally to local development. Their entrenchment, often facilitated by compliant regimes and murky contracts, speaks to the structural economic injustice embedded in France-Africa relations. The exploitation of gold and uranium, particularly in Niger and Mali, is emblematic of this inequity: while France benefits from vital raw materials, local communities suffer from displacement, environmental degradation, and poverty.

Soft power, too, has played a critical role in France’s African strategy. The dominance of French media outlets such as RFI and France 24 served not only to shape narratives but to project a carefully curated image of French benevolence and indispensability. However, African governments and civil societies have increasingly recognized and rejected this informational control. Several states have banned French broadcasters, asserting narrative sovereignty and signaling the death of media imperialism in the Sahel.

The political dimension is perhaps the most damning. The report traces a pattern of French involvement in regime changes, dating back to the 1963 assassination of Togo’s Sylvanus Olympio and the 1987 killing of Burkina Faso’s revolutionary leader Thomas Sankara. These events, it argues, are not isolated historical incidents but part of a systemic strategy to suppress radical, independent African leadership and install regimes amenable to French interests. Against this backdrop, the rise of leaders like Ibrahim Traoré represents a dramatic rupture. Despite foreign pressure, Traoré has remained defiantly committed to national sovereignty, economic justice, and pan-African ideals—emerging as a symbol of the continent’s political reawakening.

Moreover, the report exposes the weaponization of development aid and debt. It reveals how French development finance—touted as benevolent assistance—has often reinforced dependency through conditionalities that align with French corporate priorities. This debt diplomacy has locked African states into cycles of repayment and fiscal austerity, undermining long-term development and weakening domestic policy control.

In its most visionary turn, the report documents a sweeping youth-led renaissance in Africa. This generation, mobilized by frustration, injustice, and historical memory, is reclaiming the continent’s future. Drawing inspiration from past revolutionaries and harnessing the tools of modern activism, African youth are demanding dignity, representation, and economic transformation. The popularity of figures like Traoré is less a cult of personality and more a reflection of a continental yearning for authentic leadership and postcolonial liberation.

In summary, this report provides a searing indictment of France’s neocolonial machinery while spotlighting the continent’s irreversible momentum toward sovereignty, unity, and self-determination. It is both a chronicle of collapse and a declaration of emergence—a portrait of Africa no longer defined by foreign tutelage but propelled by its own will, voice, and vision.

PART 1: Introduction — France’s Colonial Mask Falls Off

1.1 The Aftermath of “Independence”: A New Form of Control

Africa’s wave of decolonization in the 20th century promised liberation, yet in many cases, independence was only skin-deep. While flags changed and national anthems were composed, the levers of control often remained in colonial hands. Nowhere has this been more evident than in France’s continued hold over its former colonies, particularly in West and Central Africa. What emerged is a web of influence known as Francafrique, a system designed to keep African nations politically subordinate, economically dependent, and militarily exposed to Paris’s reach (Le Monde Diplomatique, 2020).

1.2 What Is Francafrique?

At its core, Francafrique is France’s neocolonial strategy to retain dominance over its former African colonies. Far from being a relic of the past, it is a living structure of monetary, military, and media dominance that guarantees French interests in African affairs (Foreign Policy, 2021). Through Francafrique, France has managed to maintain a tight grip on African resources and politics without the administrative costs of direct colonial rule.

A glaring symbol of this dominance is the CFA franc — a colonial-era currency arrangement still used by 14 African nations. These countries must deposit 50% of their foreign exchange reserves with the French Treasury, while France reserves the right to appoint members to the currency’s governing board (CNRS, 2020; Bloomberg, 2022). This system helps France maintain economic stability, but for Africa, it locks nations into a cycle of dependency and restricted sovereignty (Quartz Africa, 2020).

1.3 The Military Presence: Soldiers in the Name of Stability

In the name of fighting terrorism, France has stationed thousands of troops across the Sahel, including in Mali, Niger, Chad, and Burkina Faso. These operations are often portrayed as humanitarian or stabilizing missions, but many analysts argue they are strategically designed to protect French access to uranium, gold, and other critical resources (Pan African Review, 2023; BBC Africa, 2023).

In 2023, this presence was challenged when Burkina Faso’s transitional leader, Captain Ibrahim Traoré, ordered French troops to leave the country (Al Jazeera, 2023). The move was seismic — not only a military decision but a symbolic blow against the legacy of French paternalism. For many in Burkina Faso and beyond, Traoré’s decision marked a bold reclaiming of national dignity.

1.4 The Media War: Propaganda in Plain Sight

Control over narratives has always been central to power. French media outlets such as France24 and Radio France Internationale (RFI) have long been dominant voices in Francophone Africa. While branded as independent journalism, these platforms often amplify perspectives that align with French foreign policy — portraying anti-French protests as chaotic or extremist, and leaders like Traoré as radical or dangerous (Jeune Afrique, 2021).

To counter this, Traoré banned these outlets from broadcasting in Burkina Faso, asserting the country’s right to control its own information environment. In their place, he championed Pan-African and local media as platforms for African perspectives and narratives. The shift has played a critical role in awakening civic consciousness, particularly among the youth.

1.5 The Youth Revolution: Generation Decolonize

Francafrique is not just a geopolitical issue; it’s a generational one. Across Francophone Africa, young people are refusing to inherit a system of dependence. Armed with smartphones and access to global networks, this generation is exposing the contradictions and hypocrisies of neocolonialism.

Traoré’s leadership has captured their imagination. He speaks their language — one of sovereignty, dignity, and liberation. Many liken him to Thomas Sankara, Burkina Faso’s revolutionary hero of the 1980s, or even to Che Guevara — not for ideology alone, but for what he represents: courage, principle, and defiance in the face of empire (African Arguments, 2023).

1.6 A Regional Awakening: The Sahel Bloc Emerges

Traoré’s stance has not remained within Burkina Faso’s borders. Alongside Mali and Niger, Burkina Faso has become part of a nascent alliance rejecting France’s dominance. These nations are forming new security arrangements, diplomatic fronts, and economic collaborations — all aimed at building autonomy and reducing reliance on foreign powers (UNCTAD, 2021; The Africa Report, 2022).

The creation of the Alliance of Sahel States signals a historic pivot. For decades, France served as the regional gatekeeper, leveraging its position to secure deals, deploy troops, and shape institutions. Now, that role is being actively dismantled by African leaders committed to sovereignty.

1.7 Conclusion: The Curtain Falls on Francafrique

What began as isolated acts of defiance is fast becoming a continental reckoning. Francafrique is unraveling — not by diplomatic pressure from the West or reform from within France, but by Africans who are tired of being treated as subsidiaries of a former empire.

Captain Traoré, though still a transitional figure, has become the face of this movement. His bold actions — from expelling troops to challenging media narratives — have reignited hopes for true independence across the continent. While challenges remain, the symbolism is undeniable: a generation is rising that refuses to accept the status quo.

As more African nations reconsider their relationships with France, the colonial mask continues to fall. Francafrique may not yet be gone, but its time of unchallenged dominance is over.

PART 2: The CFA Franc — A Currency of Control, Not Freedom

2.1 The Colonial Currency That Refused to Die

More than 60 years after African nations began gaining independence, a relic of colonial domination continues to haunt the continent: the CFA franc. Created in 1945 under the French colonial regime, it was never designed to empower African economies—it was built to serve France’s interests. In essence, it remains a monetary leash, keeping Francophone African countries tied to decisions made in Paris, not in African capitals (Diop, 2020).

Today, 14 African countries still use this currency. These nations are split into two zones: the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) and the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC). In both cases, real control lies not with African central banks, but with the French Treasury (Quartz Africa, 2020).

2.2 The Mechanics of Monetary Subjugation

At the heart of the CFA franc system is a mechanism that reveals its true intent. Member countries are required to deposit 50% of their foreign reserves into an “operations account” at the French Treasury (Kossi, 2022). In exchange, France guarantees unlimited convertibility with the euro at a fixed exchange rate.

While marketed as “monetary stability,” this arrangement effectively strips African states of sovereign monetary policy. France still prints the CFA franc, holds veto power over the region’s monetary decisions, and ensures that financial flows benefit French companies and investors (Sylla, 2020; Mediapart, 2022).

The result? African countries are trapped in a financial system where they absorb the shocks of eurozone policies but lack the tools to respond to their own crises (CEPR, 2021).

2.3 The Hidden Costs of “Stability”

For African economies, the price of this so-called stability is high. Pegged to the euro, the CFA franc prevents member countries from adjusting their currency in response to global economic changes. That rigidity has discouraged local production, worsened trade imbalances, and made it harder for governments to invest in industrial development (Sylla, 2020; African Development Bank, 2020).

Worse still, the CFA system undermines intra-African trade. With high transaction costs and dependence on euro-zone pricing, member countries find it more practical to export raw materials to Europe than to build value chains within the continent (UNCTAD, 2021; IMF, 2019). The dream of a united, self-sufficient African economy continues to be undermined—one CFA transaction at a time.

2.4 The Growing Rebellion Against the Franc

Across the continent, resistance to the CFA franc is swelling. From Dakar to N’Djamena, street protests and academic conferences are increasingly focused on one issue: monetary sovereignty. Activists, economists, and young people alike argue that no country can call itself free if it cannot control its own money supply (African Monetary Institute, 2021).

Among the loudest voices is Burkina Faso under Captain Ibrahim Traoré. Since assuming leadership, Traoré has criticized the CFA franc as a neocolonial tool and signaled his country’s intention to break free from it (Jeune Afrique, 2023). His administration is now exploring alternative models, and he’s not alone. Countries like Mali and Guinea are also revisiting their ties to the CFA structure.

2.5 France’s Attempt to Rebrand Control

Facing mounting criticism, France attempted a rebranding in 2020. President Emmanuel Macron and West African leaders announced the Eco, a proposed new currency to replace the CFA franc in WAEMU countries. Yet, critics quickly noted that the core mechanisms of control—the foreign reserve deposit, the fixed peg to the euro, and French oversight—remained intact (Bloomberg, 2022).

Many African economists saw this move as a public relations effort rather than genuine reform. Without structural changes, they argued, the Eco was merely “CFA franc 2.0”—another round of colonial economics wrapped in new packaging (Sy, 2021).

2.6 Toward a Pan-African Monetary Vision

Beyond the CFA, a larger conversation is unfolding. Institutions like the African Monetary Institute and African Union are advocating for a unified, continent-wide currency. This goal is rooted in the broader vision of regional integration and Pan-Africanism—a vision that includes the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) (African Monetary Institute, 2021; UNCTAD, 2021).

A single African currency could help protect nations from global currency shocks, simplify trade across borders, and empower African countries to act collectively on global financial issues. But realizing that goal requires dismantling the systems—like the CFA franc—that keep Africa tethered to its colonial past.

2.7 Conclusion: Currency as a Weapon—and a Key to Liberation

The battle against the CFA franc is not merely about economics—it’s about justice, autonomy, and dignity. For too long, African nations have been forced to operate inside a financial framework built not for them, but against them. The CFA franc is the invisible hand that shapes policies, limits choices, and stalls progress.

But that era is beginning to end. Burkina Faso, under Traoré’s leadership, is leading the charge for change. What started as academic critique is now a political movement—one that spans countries, classes, and generations.

True independence isn’t complete until Africa owns its money. And when it does, it will own its future.

PART 3: The French Military Mirage — Troops Protecting Loot, Not Lives

3.1 A Colonial Presence Masquerading as Counterterrorism

For decades, France has presented itself as a stabilizing force in Africa’s Sahel region—intervening militarily under the pretext of combating terrorism and supporting fragile states. Yet beneath the polished language of “security cooperation” and “humanitarian protection,” many African voices have uncovered a more insidious reality: France’s military operations have often shielded its economic interests, especially in resource-rich territories, while exacerbating instability on the ground (Le Monde Diplomatique, 2020).

Burkina Faso, under the leadership of Captain Ibrahim Traoré, has pulled back the curtain. In 2023, Traoré ordered the expulsion of all French military forces, marking a historic rupture with decades of foreign military dependence (Al Jazeera, 2023). His decision is not isolated but part of a broader regional revolt against military neocolonialism dressed in the fatigues of “anti-terrorism.”

3.2 The Sahel Security Façade: Operation Barkhane and Its Collapse

Launched in 2014, Operation Barkhane was the largest French military deployment in Africa since decolonization, involving over 5,000 troops across Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Chad (BBC News, 2023). Its stated aim was to counter jihadist groups and stabilize the region. Yet after nearly a decade, violence intensified, civilian deaths surged, and trust eroded.

By 2022, France was forced to end its operations in Mali, following breakdowns in relations with the Malian military government (The Guardian, 2022). The official narrative blamed the junta’s “uncooperativeness.” But analysts pointed instead to a deeper failure—France’s inability to distinguish counterterrorism from occupation (International Crisis Group, 2022). Mali’s move emboldened neighbors like Burkina Faso to reevaluate the French military’s true purpose.

3.3 Burkina Faso Breaks Free: Troops Out, Sovereignty In

Traoré’s government terminated the 2018 military agreement with France in early 2023. The formal request for French forces to leave the country within a month was met without delay (Reuters, 2023). Public celebrations erupted in Ouagadougou. For millions, the withdrawal symbolized the end of colonial paternalism masquerading as military aid (DW, 2023).

More importantly, this decision was not driven by isolationist nationalism. It was a strategic response to mounting evidence that French military bases were disproportionately located near gold mines and mineral-rich regions, particularly in northern Burkina Faso (Jeune Afrique, 2023). Rather than protecting civilians, French troops were securing zones where French multinational companies, often with opaque contracts, profited from extraction.

3.4 France’s Economic Interests: Minerals and Militarism

The Sahel is more than a terrorism hotspot—it is a resource frontier. Burkina Faso alone is home to over 800 mining sites, with gold being its most valuable export. French companies, often under the radar, have gained privileged access to these sites through strategic agreements forged during earlier regimes.

According to Le Monde Diplomatique (2020), military deployment in the Sahel cannot be separated from France’s military-industrial complex, which profits not only from arms sales but also from geopolitical leverage over African economies. The so-called “war on terror” has thus served a dual function: legitimizing a military presence and protecting extractive operations.

3.5 Regional Repercussions: The Sahel’s Shifting Alliances

The French withdrawal from Burkina Faso came amid a broader collapse of France’s military footprint in the Sahel. As of late 2022, French troops had fully exited Mali and were scaling down in Niger and Chad as well (Bloomberg, 2022). Analysts have described this as the end of the French military era in the Sahel—a region once treated as Paris’s informal backyard (The Africa Report, 2023).

Simultaneously, regional alliances have strengthened outside French influence. The Alliance of Sahel States—formed by Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger—has pledged joint defense and cooperative resource management. This shift reflects not only a security realignment but a deep political awakening against foreign occupation masked as partnership (SIPRI, 2021).

3.6 Human Rights Concerns and France’s Complicity

Amid growing militarization, human rights violations in the Sahel have multiplied. Armed forces—both domestic and foreign—have been implicated in arbitrary detentions, extrajudicial killings, and forced displacements (Amnesty International, 2022). France’s silence or indirect complicity in these abuses has further eroded its moral authority.

Rather than fostering peace, critics argue that France’s military strategies created zones of strategic occupation, where civilians were caught between jihadist threats and foreign firepower. The prioritization of mining zones and trade corridors only amplified resentment (DW, 2023). Traoré’s break from this model was thus seen not only as a matter of sovereignty but as a reclaiming of moral legitimacy.

3.7 The Mirage of Anti-Terrorism: When Occupation Fails

The failure of Operation Barkhane reflects a broader truth: you cannot bomb your way to legitimacy. France’s military operations in the Sahel lacked both a long-term strategy and community trust. While terrorism remains a legitimate threat, the root causes—poverty, marginalization, and foreign exploitation—were never addressed (International Crisis Group, 2022).

By stationing troops in mineral corridors instead of investing in social infrastructure, France deepened instability. The result was a military mirage—visible force without genuine peace.

3.8 Conclusion: Toward a New Security Ethos

The expulsion of French troops from Burkina Faso marks a historic turning point in Africa’s struggle for true independence. Traoré’s leadership has redefined national security—not as something outsourced to foreign powers, but as a function of sovereignty, community resilience, and economic justice.

France’s retreat from the Sahel is not merely a logistical issue—it is the collapse of a colonial security paradigm. For decades, Africa was treated as a terrain to be “stabilized” for Western interests. But a new generation of leaders, inspired by Pan-African values and emboldened by public will, is dismantling that narrative.

The question now is not whether Africa can defend itself. The real question is whether it will ever again allow foreign troops to define its destiny.

PART 4: Areva and Uranium — Niger Lights Paris, But Lives in the Dark

4.1 Nuclear Empires Built on African Dust

At the heart of France’s powerful nuclear industry lies a paradox that exemplifies neocolonial extraction in the 21st century: Niger, one of the world’s poorest countries, supplies the uranium that powers nearly 70% of France’s electricity (The Guardian, 2022). Yet, 90% of Nigeriens lack access to electricity themselves (World Bank, 2023). This is not just an energy gap—it is a profound injustice carved into the desert by decades of foreign exploitation.

This grotesque imbalance is made possible through the operations of Orano, formerly known as Areva, a French state-owned nuclear conglomerate. Through cozy agreements, outdated concessions, and strategic military partnerships, Orano has entrenched itself in Niger’s resource landscape for over 50 years—extracting billions in value while leaving behind environmental ruin, economic stagnation, and unlit homes (Al Jazeera, 2023; OXFAM, 2022).

4.2 Niger’s Uranium: A Strategic Resource, A Human Catastrophe

Niger is the seventh-largest uranium producer in the world, and uranium accounts for over 60% of the country’s exports (Global Witness, 2021). Its key mining sites—Arlit and Akokan—located in the northern Agadez region, have long been controlled by Orano. Yet, the wealth extracted from the earth rarely translates into prosperity for the Nigerien people.

Despite being the backbone of France’s nuclear energy program, Niger receives shockingly low royalties, averaging between 5% and 12% of the total export value (OXFAM, 2022). France, meanwhile, ensures long-term supply stability, paying fixed prices that benefit French consumers while decoupling Niger’s potential gains from volatile global markets (France 24, 2023).

Reuters (2023) noted that even during recent political unrest, France’s uranium shipments from Niger remained “unaffected”—a chilling indication of how deeply embedded these operations are, regardless of the socio-political context.

4.3 The Radiation Toll: A Hidden Public Health Crisis

While the uranium glows in reactors across France, the mining towns of Niger are plagued by radiation exposure, contaminated water, and soaring cancer rates. According to Médecins du Monde (2020), local communities in Arlit suffer from elevated cases of lung disease, birth defects, and unexplained illness—symptoms consistent with long-term radiation exposure.

Human Rights Watch (2020) reports that Areva/Orano has failed to provide adequate environmental remediation or transparency around radiation levels. Even former mine workers have been denied proper medical care or compensation, despite decades of service under hazardous conditions.

The industry’s defenders point to Orano’s own Sustainability Report (2022), which claims adherence to “global environmental standards” and “local development goals.” But these claims are sharply contradicted by ground-level investigations that reveal radioactive waste being dumped near residential areas and water sources (OXFAM, 2022; Médecins du Monde, 2020).

4.4 Darkness at Home: Niger’s Electricity Crisis

The most striking indictment of this extractive relationship is not just in the mine shafts or toxic air, but in the darkness that covers Niger each night. As of 2023, over 19 million Nigeriens lack access to electricity, making Niger one of the least electrified countries on Earth (World Bank, 2023).

While Paris basks in uninterrupted nuclear-powered light, villages near Arlit often depend on diesel generators—when fuel is available—or go without energy altogether (DW, 2022). This cruel irony illustrates the structural violence embedded in colonial economics: the resource is exported, the value is captured abroad, and the burden is left behind.

4.5 Following the Money: Who Really Profits?

According to Global Witness (2021), Orano’s Niger operations are structured to minimize tax obligations and maximize profit repatriation. Complex transfer pricing mechanisms, offshore entities, and vague concession contracts allow the company to report minimal taxable income in Niger while maintaining high margins in France.

The deals signed during the heyday of Francafrique—with little transparency or public accountability—continue to bind Niger into a system of perpetual underdevelopment, even as its soil delivers energy to Europe’s richest nation (France 24, 2023; Le Monde Diplomatique, 2020).

Despite claims of “corporate responsibility,” data from the Bloomberg (2023) and The Guardian (2022) confirm that Orano remains one of France’s most strategically important resource extractors in Africa—a private actor, but deeply entangled with French national interests.

4.6 A Continental Response: Solidarity and Resistance

The uranium question has evolved beyond Niger. Under the leadership of Captain Ibrahim Traoré, Burkina Faso has thrown its weight behind resource sovereignty, supporting Niger’s efforts to renegotiate its mining contracts and increase national control over strategic sectors (Al Jazeera, 2023). This alliance reflects a growing Pan-African awakening, where military, monetary, and resource liberation are seen as interlinked fronts in the struggle for full independence.

In public statements, Traoré has emphasized that true freedom requires control over what lies beneath African soil—a sentiment echoed by activists across West Africa calling for the nationalization of mineral wealth and an end to exploitative deals (OXFAM, 2022; DW, 2022).

4.7 France’s Delicate Dependency

Despite official reassurances, France’s energy sector is deeply vulnerable to disruption from Niger. Nearly one-third of Orano’s uranium comes from the country, and any sustained supply interruption could send shockwaves through Europe’s nuclear market (Bloomberg, 2023).

This dependency gives Niger and its allies new leverage—but only if they are willing to endure the diplomatic and economic consequences of defying French interests. So far, with the rejection of French troops, CFA currency systems, and now mining contracts, Sahelian nations are signaling they are ready for that fight.

4.8 Conclusion: Uranium, Power, and Post-Colonial Reckoning

Niger’s uranium paradox captures the essence of France’s post-colonial grip on Africa: the illusion of partnership masking a reality of one-sided extraction and enduring poverty. The people who dig the uranium live in darkness, while the consumers thousands of miles away enjoy endless light. The miners inhale toxic dust while stockholders cash dividends.

This is not just an economic model—it is a moral crisis. And as leaders like Traoré challenge the pillars of Francafrique, uranium has become a symbol of resistance, of reawakening, and of the unyielding demand for a future powered by African hands—for African benefit.

PART 5: Total, Bolloré, and the Corporate Colonialism Game

5.1 From Gunboats to Shareholders — Colonialism in Corporate Form

The age of direct colonial rule may be over, but the apparatus of economic domination is alive and well. It wears suits, controls contracts, and moves through international boardrooms—not army barracks. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the operations of French multinational giants like TotalEnergies and Bolloré in Africa. Though cloaked in the rhetoric of partnership and investment, these corporations have built what critics call a “corporate colonial empire,” extracting massive profits while leaving African economies dependent and underdeveloped (Oxfam, 2022; Al Jazeera, 2023).

Together, Total and Bolloré have come to symbolize a new frontier of neocolonialism—one that controls oil fields, ports, railroads, and state institutions across Francophone Africa. Their influence is systemic, spanning infrastructure, energy, trade, and politics. Their business models replicate the same extractive relationships of the colonial era—only now, they are enforced not by the French army, but by legal contracts, monopolies, and backroom deals (Mediapart, 2022; Transparency International, 2023).

5.2 TotalEnergies: Oil, Power, and Disguised Dependency

TotalEnergies (formerly Total) has long been entrenched in African oil economies. From Nigeria to Angola, and particularly in Francophone states like Gabon and Congo-Brazzaville, Total has positioned itself as an indispensable player. Yet beneath its glossy reports of “energy partnerships” lies a troubling truth: Total pays some of the lowest royalties on the continent, while extracting billions in revenue annually (Oxfam, 2022; Jeune Afrique, 2022).

For example, in 2022 alone, Total’s African operations generated an estimated $10.4 billion in revenue, yet contributed less than 5% of that in direct taxes or royalties to host governments (Bloomberg, 2023). Contracts are often signed under opaque terms, during moments of political transition or crisis. In many cases, state negotiators are under-resourced, poorly advised, or compromised by foreign lobbying (The Africa Report, 2022).

The result is a model where resource-rich nations remain cash-poor, locked into agreements that prioritize shareholder returns in Paris over schools and hospitals in Port-Gentil or Pointe-Noire. Critics have labelled it “profit without accountability”, arguing that Total’s operations deepen dependency rather than promote development (Oxfam, 2022).

5.3 Bolloré: The Empire of the Docks

If Total dominates African oil, Bolloré ruled its logistics. For decades, the Bolloré Group controlled a vast network of ports, railroads, and warehouses across West and Central Africa—effectively becoming the gatekeeper of African trade. Before partially selling its African logistics arm in 2022, Bolloré operated in over 16 countries, managing flagship ports in Abidjan, Douala, and Conakry (France24, 2022; The Africa Report, 2022).

This dominance was built not on innovation but on strategic monopolies, sweetheart concessions, and long-term contracts that often excluded local competitors. According to Transparency International (2023) and DW (2022), Bolloré’s model has discouraged investment in local port authorities, limited sovereign control over trade infrastructure, and siphoned millions in annual fees to French coffers.

In effect, Bolloré privatized not just African ports—but African sovereignty over its own borders and customs systems.

5.4 Corruption and Capture: How the Game Is Played

Bolloré’s business practices have long raised red flags among anti-corruption organizations. In 2023, the company was fined by Ivorian courts for its role in a bribery scandal linked to port deals in Abidjan. Investigations revealed how Bolloré used media and advertising subsidiaries to support political campaigns in exchange for favorable concessions (Reuters, 2023; OECD, 2021).

This form of “corporate state capture” is not isolated. It reflects a broader pattern whereby French companies operate not just within African markets—but within African politics. In many instances, they become kingmakers—funding campaigns, influencing ministries, and shaping infrastructure priorities to serve their bottom line (Mediapart, 2022; Al Jazeera, 2023).

5.5 The Exit That Wasn’t: Bolloré’s Shadow Lingers

Although Bolloré sold its African logistics division to MSC (Mediterranean Shipping Company) in 2022 for €5.7 billion, critics argue this was a rebranding exercise, not a retreat (France24, 2022). Many of the management structures, port contracts, and local partnerships remain unchanged. The influence continues under new names, with the same networks still in place (The Africa Report, 2022).

Jeune Afrique (2022) notes that key contracts were transferred with little transparency or renegotiation, meaning the new players inherited the old deals—some of which stretch 20 to 30 years into the future. For many African states, the question remains: who controls our ports? And who really benefits from our trade?

5.6 Infrastructure as Extraction: The French Logistics Doctrine

Beyond corruption, the core critique of French logistics companies in Africa is strategic: their infrastructure does not integrate economies—it extracts from them. According to the African Development Bank (2022), much of Africa’s port and rail infrastructure built under French companies serves export corridors for raw materials, not internal trade routes or regional supply chains.

Thus, African goods—cocoa, oil, gold—flow efficiently outward, while intra-African trade remains among the lowest in the world, under 15%. This is not accidental; it’s the result of decades of infrastructure built for European benefit, under European control (DW, 2022; Transparency International, 2023).

5.7 Traoré’s Response: Audits, Reviews, and Resistance

Captain Ibrahim Traoré has not ignored this reality. Since assuming leadership in Burkina Faso, his government has launched a sweeping review of all foreign contracts, particularly in mining, energy, and logistics (Al Jazeera, 2023). French companies are under increased scrutiny, and some are being pressured to renegotiate terms or risk expulsion.

Traoré’s stance is not only legal—it is ideological. His administration views infrastructure as a strategic asset, not a commodity to be leased indefinitely. In his vision, ports, pipelines, and logistics networks must serve the national interest, not foreign shareholders.

5.8 Conclusion: From Concessions to Confrontation

The case of Total and Bolloré reveals a deeper truth: colonialism never left—it was privatized. Through oil contracts and port concessions, two French giants maintained control over African economies long after the tricolor flag was lowered.

But the tide is turning. African leaders, journalists, economists, and civil society actors are questioning the legitimacy of these arrangements. Traoré’s Burkina Faso represents the sharp edge of this resistance—demanding not just fair contracts, but a new paradigm: one in which African infrastructure is owned by Africans, for African prosperity.

The era of “business as usual” is coming to an end. What follows may finally be the decolonization Africa was promised—but never truly received.

PART 6: Political Puppetry — France’s Hand in African Coups

6.1. The Coup Behind the Curtain

For decades, Africa has been haunted by an unending carousel of coups, particularly in Francophone West Africa. Behind many of these power shifts—both historic and recent—lurks the spectral hand of a former colonial power: France. While Paris publicly champions democracy, human rights, and constitutional order, a closer examination of its post-colonial legacy reveals a far murkier reality: one of quiet complicity, strategic ambiguity, and selective outrage (Al Jazeera, 2023; DW, 2023).

From Togo in 1963 to Niger in 2023, France has been implicated in either engineering, enabling, or tacitly endorsing regime changes that favored its geopolitical and economic interests. This covert role—dubbed “Francafrique 2.0”—has morphed from direct military interventions into more refined instruments: economic leverage, elite co-optation, and strategic silence (Columbia University, 2023; Mediapart, 2023).

6.2 Coups with Colonial Fingerprints: A Historical Pattern

France’s entanglement in African political upheavals dates back to the very foundations of “independence.” In 1963, Togo’s first president Sylvanus Olympio was assassinated after attempting to establish monetary autonomy from the CFA franc. His replacement, Gnassingbé Eyadéma, enjoyed decades of French support (Jeune Afrique, 2022). Similarly, the 1987 assassination of Burkina Faso’s revolutionary leader Thomas Sankara—and the rise of pro-French strongman Blaise Compaoré—reflected France’s intolerance for leaders who defied neocolonial structures (The Africa Report, 2023).

These are not isolated events. According to Oxfam (2022), elite capture in Francophone Africa often requires foreign endorsement, and France has long been adept at supporting regimes willing to uphold economic subordination, even at the cost of democracy.

6.3 The Strategic Silence of the Republic

When coups align with France’s interests, its response tends to be muted, diplomatic, or delayed. When they threaten French hegemony, outrage ensues. Consider Mali (2021), Burkina Faso (2022), and Niger (2023)—three Sahelian nations where anti-French sentiment coalesced with military takeovers. In these instances, France issued vague condemnations but quickly pivoted to protect strategic assets, including military bases and mining operations (Reuters, 2023; African Arguments, 2023).

France24 (2022) reported that French officials denied involvement in the Burkina Faso coup that brought Captain Ibrahim Traoré to power. However, the persistent suspicion on the ground, fueled by decades of French meddling, undermined the credibility of such denials. DW (2023) noted that Paris’s “strategic silence” often signals tacit approval or at least a willingness to adapt swiftly to new realities—as long as French interests remain unharmed.

6.4 The Architecture of Influence: Military Bases and Client Regimes

France maintains numerous military installations across West Africa, notably in Djibouti, Chad, Ivory Coast, and until recently, Mali and Burkina Faso. These bases serve dual purposes: counter-terrorism (officially) and geopolitical control (unofficially) (Columbia University, 2023). Military dependence often makes African leaders vulnerable to French pressure—whether that involves maintaining military presence, suppressing opposition, or rubber-stamping exploitative contracts.

The Columbia SIPA report (2023) exposes how these military alliances function as informal pacts of protection: France supports compliant regimes in exchange for continued access to resources and regional influence. This arrangement has often meant turning a blind eye to authoritarianism, election fraud, and human rights abuses (Human Rights Watch, 2023).

6.5 From Francafrique to Francafailure: The Revolt Against Puppet Regimes

A growing number of African citizens are no longer buying the illusion of partnership. Protests across Bamako, Ouagadougou, and Niamey have called out France’s role in sustaining illegitimate governments that fail to deliver on justice, security, or dignity (Bloomberg, 2023).

These aren’t fringe movements. In 2023, a wave of youth-led uprisings in the Sahel made clear that the era of French-backed autocrats is nearing its end. According to The Africa Report (2023), many view the coups not as power grabs, but as corrective revolts against colonial structures disguised as democratic institutions.

Burkina Faso’s Captain Traoré exemplifies this shift. While the West brands him a populist “junta leader,” many Africans see in him a new generation of sovereign-minded leadership—unwilling to be puppeteered by external actors, French or otherwise (DW, 2023; Al Jazeera, 2023).

6.6 France’s Double Game: Democracy as Diplomacy, Autocracy as Strategy

France’s foreign policy remains steeped in paradox. It publicly promotes democracy, yet its historical alliances suggest a preference for stability over sovereignty—even if that stability is maintained through repression.

Human Rights Watch (2023) details how France has continued to arm, finance, and train forces loyal to authoritarian regimes across West Africa, despite well-documented abuses. In Chad, for example, France stood by as Mahamat Déby seized power following his father’s death—without an election. Paris’s rationale? “Continuity in the fight against terror.”

This selective morality undermines France’s credibility and reinforces the belief that its commitments to democracy are negotiable when economic or military interests are at stake (France24, 2022; DW, 2023).

6.7 Ghosts of Influence: The Psychological Legacy of Meddling

The damage of France’s coup diplomacy is not only political—it is psychological. Generations of African leaders have risen to power with the implicit understanding that sovereignty ends where French interests begin. This unspoken doctrine—perpetuated through language, education, and elite networks—has stunted the emergence of independent, visionary governance (Oxfam, 2022; Mediapart, 2023).

Even when France is not directly involved, its historical fingerprints influence how coups are interpreted. As African Arguments (2023) notes, every shift in power is viewed through the lens of France’s shadow, creating a trust vacuum that weakens African political institutions from within.

6.8 Conclusion: France’s Strategic Playbook Is No Longer a Secret

The myth of France as a neutral arbiter or benevolent ally in African affairs has collapsed. The reality, increasingly laid bare, is one of systematic interference, elite manipulation, and geopolitical hypocrisy. As more African nations reclaim their political agency, France finds itself exposed, untrusted, and unwelcome—not because of propaganda, but because of a long history of treating African sovereignty as negotiable.

The Sahel’s coups are not random acts of military ambition. They are the aftershocks of decades of political puppetry, in which France pulled the strings, then feigned surprise at the fallout. What remains now is a continent demanding not just new leaders, but a new political architecture—free from external domination.

The age of silent complicity is over. The hands behind the curtain are now in plain view.

PART 7: Media Warfare — France24, RFI, and the Colonial Echoes of Information Control

7.1. When the Mic Becomes the Baton

For much of the post-independence era, France retained its presence in Africa not only through the military and currency systems but also through media imperialism—a subtler yet potent arm of soft power. Through state-funded broadcasters like France24 and Radio France Internationale (RFI), the French government has curated narratives, shaped perceptions, and undermined African sovereignty in the realm of information (France Diplomatie, 2022; Columbia Journalism Review, 2022).

The power of these media outlets lay not merely in news reporting but in agenda setting—positioning France as a rational, stabilizing force while painting African movements for independence, nationalism, or reform as destabilizing, irrational, or extremist. However, a dramatic shift is underway. Led by figures like Captain Ibrahim Traoré of Burkina Faso and Assimi Goïta of Mali, Sahelian states are not only rejecting France’s military and economic grip, but also ejecting its media mouthpieces from their airwaves (Al Jazeera, 2023; DW, 2023).

7.2 The Media Complex: Soft Power as Strategy

France’s global media presence is coordinated through France Médias Monde, a government-backed enterprise that manages France24, RFI, and Monte Carlo Doualiya. This media conglomerate operates in over 180 countries and is explicitly tied to France’s foreign policy objectives (France Diplomatie, 2022).

Under the guise of objective journalism, these outlets have often amplified French diplomatic narratives. For instance, insurgencies in the Sahel are commonly framed through the lens of terrorism and instability—with little regard for the underlying grievances of local populations, such as poverty, foreign exploitation, or historical injustices (African Arguments, 2023; Columbia Journalism Review, 2022).

This editorial bias becomes especially visible during political transitions. Leaders like Traoré and Goïta—who rise through anti-French populism—are framed as “junta leaders,” while France-backed presidents are described as “constitutional,” regardless of their actual democratic legitimacy (Jeune Afrique, 2023; Quartz Africa, 2023).

7.3 Censorship or Self-Defense? Banning the Broadcasters

In March 2023, Burkina Faso suspended France24, citing its decision to air an interview with an Al-Qaeda affiliate without adequate editorial framing (Al Jazeera, 2023). Days later, RFI was also banned, accused of broadcasting false information and stirring panic. The government defended the bans as a matter of national security and informational sovereignty—not censorship (Reuters, 2023; BBC, 2023).

Mali and Niger quickly followed, citing similar concerns about biased coverage and misinformation (DW, 2023). Critics in Western media decried these moves as authoritarian. But within these countries, public sentiment largely supported the decision. According to The Africa Report (2023), local journalists, activists, and scholars increasingly view these media outlets as extensions of French foreign policy, not neutral informants.

7.4 Propaganda by Omission: What France24 and RFI Don’t Say

The power of imperial media is not just in what it reports—but what it chooses to omit. France24 and RFI rarely examine the economic structures that underpin instability in the Sahel: the CFA franc, mining concessions to French companies, or the role of foreign troops in strategic resource zones (Le Monde Diplomatique, 2023).

When these topics are addressed, they are often wrapped in technocratic jargon or obscured through a “both sides” narrative that erases France’s historical culpability. This omission protects France’s image while demonizing African efforts toward self-determination (African Arguments, 2023; Quartz Africa, 2023).

Moreover, these outlets have been accused of consistently underreporting human rights violations by French troops, while sensationalizing abuses committed by African forces. This informational asymmetry has eroded public trust in France’s so-called “free press” across the Sahel (Reporters Without Borders, 2023).

7.5 Soft Power Losing Its Grip

For decades, France’s soft power in Africa was unrivaled. Scholarships to French universities, cultural institutions like the Institut Français, and media like RFI ensured that Francophone elites were trained to think, speak, and act in alignment with Paris. But this model is rapidly collapsing.

The digital revolution has democratized media production and consumption. In Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, a new wave of Pan-African media platforms—from online publications to YouTube political analysts—has emerged to challenge dominant narratives and reclaim the African story (The Africa Report, 2023; African Arguments, 2023).

This evolution terrifies Paris—not because it threatens journalism, but because it threatens control. As more Africans get their news from Pan-African sources, the relevance of French state media continues to plummet.

7.6 The Double Standards of “Press Freedom”

Western institutions often cite the banning of France24 and RFI as examples of press repression. Yet these same voices remain largely silent when Western states apply similar measures under the banner of national interest.

For instance, during the Ukraine war, the EU banned Russia Today (RT) across the bloc for “spreading disinformation.” This precedent makes France’s outrage over being banned in Africa deeply hypocritical (BBC, 2023; Le Monde Diplomatique, 2023).

In this light, the bans enacted by Sahelian governments are not attacks on journalism—they are acts of decolonial resistance against informational occupation.

7.7 A New Age of Communication Sovereignty

Captain Traoré has taken the concept of sovereignty into the digital battlefield. He speaks directly to the people of Burkina Faso via national broadcasts, social media, and carefully coordinated press briefings—bypassing French channels altogether (Reuters, 2023; African Arguments, 2023).

This direct-to-citizen model has become a blueprint for leaders across the Sahel, who are asserting control over their narrative space and refusing to let their revolutions be mediated through colonial filters. What once required a coup d’état now begins with a Twitter thread or a YouTube video. And the people are listening.

7.8 Conclusion: The Last Broadcast of Empire

The expulsion of France24 and RFI marks more than a media blackout—it is the end of an era. In the past, empires needed soldiers and flags. Today, they rely on satellites and talking heads. But the function is the same: to dominate the imagination, to dictate who is civilized, who is dangerous, who is worthy of freedom.

The Sahel has begun to reject this soft colonialism. Through bold action, African states are reclaiming their informational sovereignty—insisting not only on the right to govern themselves, but to tell their own stories, in their own voice, for their own people.

The signal may be off. But for Africa, the volume is finally rising.

PART 8: The Youth Rebellion France Can’t Bribe

8.1 The Fall of Influence: A New Fire Rises

Across the once-silent boulevards of West Africa, a new generation is rising. These are not the youth of old—tempered into silence by political fear or shackled by the invisible chains of dependency. No. This generation is different. Their rebellion is not rooted in violence but in the power of consciousness, solidarity, and unflinching clarity. From the alleyways of Bamako to the campuses of Ouagadougou, they are speaking, marching, organizing—and they cannot be bought.

The youth rebellion in Francophone Africa is not merely a protest against poor governance. It is a seismic shift in identity and allegiance, a public renunciation of France’s long-standing soft-power dominance. Decades of influence, carefully crafted through scholarships, media channels, and NGO relationships, are now crumbling under the weight of African awakening. These young citizens are rejecting the psychological grip of the colonizer—loudly, proudly, and without compromise.

8.2 The Crumbling Empire of Soft Power

For years, France relied not solely on military or economic levers, but on the subtle tools of soft power: the glowing prestige of French universities, the allure of French-language media, and the enticement of humanitarian aid through French-backed NGOs. These were not just instruments of goodwill—they were strategic assets designed to maintain cultural hegemony long after independence had been won.

France’s media houses like RFI and France 24 were positioned as neutral voices in African news, but are increasingly seen by young Africans as colonial megaphones. Scholarships to Parisian institutions were once regarded as golden tickets to the global elite; now, many view them as golden handcuffs—benefits laced with ideological expectations. Civil society partnerships once welcomed are now scrutinized for their agendas.

This shift didn’t occur overnight. It has been catalyzed by growing access to the internet, social media, and independent Pan-African voices. What was once hidden behind diplomacy is now dissected on TikTok and X (formerly Twitter). Propaganda falters in the face of decentralized truths.

8.3 The Rise of Unbribable Youth Movements

From Dakar to Niamey, youth-led movements have emerged not only as opposition voices but as the conscience of a continent. These are movements fueled not by foreign grants but by grassroots energy. Their slogans carry more than just anger; they are manifestos of Pan-African rebirth.

In Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, we see an electrifying push against political puppetry and neocolonial dependence. These movements reject both the political old guard and the external forces that prop them up. France’s influence is no longer challenged with whispers—it’s met with chants in the streets, digital resistance, and cultural insurgency.

A defining feature of these movements is their immunity to bribery. The youth have seen what happens when their elders are absorbed into the system—silence, compromise, and the slow death of national dignity. They have also seen how aid money often becomes elite wealth while communities remain impoverished. So they demand a different path: integrity over convenience, sovereignty over sympathy.

8.4 Traoré: The Symbol of Youth Defiance

Amidst this generational shift, one figure has emerged as a unifying symbol: Captain Ibrahim Traoré of Burkina Faso. Charismatic, young, and uncompromising, Traoré has become the face of a new Pan-African defiance. He is not revered for his military credentials alone, but for what he represents—a break from the old order.

Traoré speaks the language of the streets. He echoes the frustrations of the youth and amplifies their demands for a reimagined Africa. In an era where many African leaders are seen as reluctant reformers, Traoré has positioned himself as a revolutionary. Under his leadership, Burkina Faso has restructured its foreign alignments, pushed back against French military presence, and committed to Pan-African cooperation that prioritizes African interest over European appeasement.

To the youth, Traoré is not a savior but a mirror. He reflects their beliefs, their refusal to be docile, their dreams of an Africa that does not apologize for its power. His refusal to be seduced by diplomatic platitudes has only cemented his place in their hearts.

8.5 The Cultural Frontline: Rappers, Bloggers, and Digital Rebels

This rebellion is as much cultural as it is political. Today’s African youth do not simply protest through slogans—they weaponize poetry, music, memes, and livestreams. The frontline of resistance includes rappers who spit verses about liberation, bloggers who dismantle foreign propaganda, and digital creators who reimagine African futures.

Artists like Smockey in Burkina Faso and Didier Awadi in Senegal have turned their craft into resistance. Songs once censored now trend on underground platforms. Lyrics no longer praise the state—they interrogate it. Music videos become viral critiques of French neocolonialism and domestic betrayal.

Meanwhile, online spaces once dominated by foreign voices are now repurposed as arenas of Pan-African thought. YouTube, X, Instagram, and Telegram channels provide uncensored forums for political education, organizing, and identity assertion. Young Africans no longer wait for permission to narrate their story. They own the camera, the microphone, and the feed.

In rejecting France’s narrative, they are building their own. They are refusing the cultural inheritance handed down by colonialism and scripting new legacies rooted in self-respect.

8.6 The Fall of Elite Diplomacy

France has long relied on elite diplomacy—cultivating relationships with African presidents, ministers, and technocrats who could be trusted to maintain the status quo. Lavish state visits, bilateral roundtables, and symbolic handshakes formed the choreography of control.

But the youth rebellion has exposed the fragility of this model. Presidents may nod in Paris, but their people shake their fists in Ouagadougou. What was once behind closed doors now spills onto timelines. Every concession, every compromise, every foreign agreement is scrutinized, criticized, and, when necessary, rejected.

The legitimacy once bestowed by proximity to France now invites suspicion. Youth no longer view alignment with France as prestige—they see it as betrayal. Leaders who accept French backing often lose the trust of their own populations.

This is the death knell of elite diplomacy in Africa. Its era is ending, not because of foreign withdrawal, but because of domestic awakening.

8.7 Pan-Africanism Reborn

What makes this youth rebellion especially potent is its philosophical foundation. It is not merely a reaction—it is a vision. A revival. A rediscovery of Pan-Africanism not as theory but as praxis.

This rebirth unites language groups, tribal identities, and colonial histories. It says that the borders drawn by Europeans are not our destiny. It declares that unity is strength, that African problems require African solutions, and that freedom must be economic, cultural, and psychological.

Young Pan-Africanists are not content with blaming France alone. They are interrogating their own institutions, dismantling internal colonial structures, and redefining what it means to be African in the 21st century. They seek alliances with like-minded nations, global south partners, and diasporic voices that align with sovereignty and dignity.

In this vision, France is not the enemy—it is a relic. And relics are remembered, not obeyed.

8.8 The War for Minds: France’s Failing Response

In response to this awakening, France has scrambled to salvage its influence. Media houses ramp up public relations campaigns, embassies launch youth empowerment initiatives, and think tanks publish white papers on “renewing trust.” But the youth are not impressed.

They see through the spin. They remember the duplicity of interventions disguised as peacekeeping. They question the value of media that never questions Paris. They ask: how can a nation that preaches liberty abroad still control currencies in Africa?

France’s soft-power arsenal—once its strongest suit—has become a burden. Its every move is suspect. Its offers are refused. Its former admirers are now its fiercest critics.

What France is learning too late is this: you cannot bribe those who have found purpose. You cannot colonize those who have decolonized their minds.

8.9 The Continent’s Crossroads

This moment is a crossroads for Africa. It is also a test. Will this youth rebellion become the foundation of a new system or collapse under the weight of resistance? Will Pan-African dreams translate into institutions, policies, and transnational movements? Or will the inertia of old systems reclaim the narrative?

What is certain is this: Africa’s youth are no longer waiting. They are building schools that teach real history. They are creating tech that serves African needs. They are cultivating a culture of questioning, and from it, a culture of building. They are not the future—they are the present reshaping the past.

This movement may be fragmented, and its victories uneven, but its direction is clear. The call is for real independence. The demand is for reparative justice. And the dream is no longer deferred.

8.10 Conclusion: Irreversible Consciousness

The youth rebellion France can’t bribe is not just about geopolitics—it’s about dignity. It is the loud, defiant, and beautiful insistence that African voices matter, that African futures belong to Africans, and that liberation is a daily act.

France may recalibrate. It may offer new aid packages, organize cultural summits, or rebrand its embassies. But the tide has turned. Influence rooted in dominance cannot coexist with a generation that knows its worth.

From lyrics to legislation, from slogans to systems, this rebellion is rewriting the rules. It is creating a continent where respect is earned, not begged; where leaders serve, not rule; and where foreign interests are welcome only if they align with African aspirations.

This is not the Africa of dependency. This is not the Africa of permission. This is the Africa of will—driven by its youth, unshackled by its past, and unstoppable in its course.

Read also: British Empire’s Corruption And Exploitation In Nigeria

PART 9: Education and Language — The Final Frontier of Colonial Domination

9.1 The Invisible Chains of the Mind

While military occupation and economic dependency are readily visible, one of the most pervasive and underexamined legacies of French colonialism in Africa lies in the sphere of language and education. It is here—in blackboards, textbooks, and national exams—that France’s soft grip continues to mold African thought, identity, and governance.

In most Francophone African countries, French remains the official language of education, law, and government—despite being a foreign tongue to the vast majority of citizens. It is the medium through which students access knowledge, the language in which laws are drafted, and the primary mode of elite communication. As Oxfam (2022) and Oxford Economics Africa (2022) note, this linguistic dominance is not neutral: it is a calculated strategy that entrenches economic hierarchies, stifles indigenous knowledge systems, and ensures continued dependency on former colonial institutions.

9.2 French as the Language of Power and Exclusion

In theory, language should be a tool for inclusion. In post-colonial Francophone Africa, however, it functions as a gatekeeper to power. Fluency in French is the price of admission into the civil service, academia, or international diplomacy. Yet, in most of West and Central Africa, less than 30% of the population speaks fluent French, and even fewer speak it as a first language (Quartz Africa, 2022).

This creates what Jeune Afrique (2023) calls a “linguistic elite caste”—a small minority fluent in French who dominate national discourse, policymaking, and resource allocation. The rural and urban poor, whose native languages are Wolof, Bambara, Fulfulde, or Mooré, are largely shut out of political participation and public life.

Language, in this context, is not a unifying national force—it is an instrument of stratification, maintaining a class divide rooted in colonial history (Al Jazeera, 2023; DW, 2023).

9.3 Colonial Curricula: Sanitizing Empire, Silencing Resistance

Language is only the beginning. What is taught—and how it is taught—is equally significant. Across much of Francophone Africa, education systems still reflect the epistemological frameworks of the French colonial state. As The Africa Report (2023) highlights, history textbooks often glorify French civilization, minimize African resistance movements, and erase indigenous governance systems.

This colonial pedagogical framework encourages students to identify with France’s version of history, seeing colonization as a civilizing mission rather than a violent economic enterprise. It also means that Pan-African thinkers, anti-colonial revolutionaries, and local intellectual traditions are marginalized or erased altogether (Oxford Economics Africa, 2022).

The result is a generation of students more familiar with Rousseau and Molière than with Thomas Sankara or Cheikh Anta Diop—a strategic outcome, not an accidental omission.

9.4 Francophone Institutions: Gatekeepers of Cultural Dependency

The entrenchment of French language and thought is also reinforced through a dense web of French-funded institutions, including the Institut Français, AUF (Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie), and a range of bilateral education programs. These institutions offer scholarships, research partnerships, and cultural programming—but often at the cost of epistemic independence.

According to Mediapart (2023) and France24 (2022), these initiatives serve dual purposes: promoting the French language and maintaining ideological alignment with Paris. Even where curricula are “Africanized,” funding structures and teaching materials still trace back to French institutions, leaving African education colonized in content, form, and funding.

9.5 The Economics of Linguistic Dependency

The colonial education model is also economically parasitic. African governments spend millions annually to import French-language textbooks, fund French-language exams, and train teachers in foreign pedagogical standards. This fiscal burden—compounded by an already fragile public finance system—limits investment in locally relevant and inclusive education models (Oxfam, 2022; African Development Bank, 2023).

Moreover, the dominance of French in higher education and business locks African economies into French-speaking markets and partnerships, stifling economic diversification and deepening dependency. Bloomberg (2023) reports that language barriers impede regional integration, particularly with Anglophone neighbors and emerging Asian and Arab markets.

As The IMF (2022) notes, linguistic alignment with a former colonial power creates structural inefficiencies in trade, finance, and knowledge production.

9.6 Traoré’s Cultural Revolution: Decolonizing the Classroom

Captain Ibrahim Traoré’s government in Burkina Faso has recognized the centrality of education in the broader decolonization struggle. In 2023, his administration announced reforms to incorporate national languages into primary education, while also promoting Pan-African history and indigenous knowledge systems in secondary curricula (Al Jazeera, 2023; Jeune Afrique, 2023).

This bold step is more than symbolic. It signals a rejection of the myth that French is the sole vehicle of progress, and it reflects a desire to cultivate cultural self-respect and cognitive liberation. Traoré has argued that true sovereignty cannot exist without mental decolonization, and education is the battlefield where this must occur.

9.7 The Battle for the Mind: Cultural Liberation and Resistance

Language is not simply a tool for communication; it is the architecture of thought. As long as Francophone Africa thinks in French, dreams in French, and educates its children in French, its independence will remain partial and performative.

This linguistic imperialism is reinforced by the broader Francafrique ecosystem, in which economic, political, and cultural levers all reinforce one another. As The Africa Report (2023) and IMF (2022) argue, the fight for a new currency, for fair contracts, and for self-governance will be incomplete if the minds of future leaders are still shaped by colonial frameworks.

This is why France continues to invest heavily in its cultural influence across Africa. As its military and economic grip weakens, its last stronghold may well be the classroom.

9.8 Conclusion: From Linguistic Chains to Liberation

Francophone Africa’s path to liberation will not be paved by coups alone, nor by contracts or currency reform. It must also pass through the classroom, the library, the language policy, and the curriculum. The colonization of the mind is France’s most enduring legacy, and breaking that chain is the most formidable task ahead.

A sovereign Africa must think in its own languages, teach its own histories, and build its own intellectual traditions. As Captain Traoré and others have begun to assert, the decolonization of education is not a cultural issue—it is a strategic necessity.

For only when the African child learns who they are, in the words of their ancestors, will the continent begin to fully reclaim its future.

PART 10: France’s Fear of a United Sahel — The Military Exodus and Rise of African Sovereignty

10.1 From Military Might to Political Fallout

In the wake of decades of military interventions justified by counterterrorism, France now finds itself in strategic retreat across the Sahel. Its once-formidable military footprint, anchored by Operation Barkhane, has steadily crumbled under the weight of anti-colonial backlash, growing Pan-African sentiment, and a surge of leaders demanding true sovereignty. The Sahel states—Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger—have emerged as the vanguard of this revolt, not just in rejecting foreign troops but in forming a bold, collective alternative to France’s long-standing regional dominance (Al Jazeera, 2023; Reuters, 2023).

At the heart of this geopolitical shift is Captain Ibrahim Traoré, the Burkinabè military leader who has inspired a new regional assertiveness. The formation of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES)—a trilateral pact of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger—is no coincidence. It is a deliberate rejection of France’s neocolonial scaffolding, and a strategic step toward a self-determined Sahel future.

10.2 The Fall of Barkhane: End of the Colonial Sword

Operation Barkhane, launched in 2014, was once heralded as the centerpiece of France’s anti-terror operations in Africa. With thousands of troops stationed across Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad, it was presented as a bulwark against jihadist insurgencies. But over time, local populations began questioning its effectiveness—and its motives (Brookings Institution, 2022).

Despite billions in military spending, terrorism flourished, insecurity deepened, and trust in France plummeted. Critics argued that French forces were more concerned with protecting strategic mining corridors and geopolitical interests than actually securing civilians (BBC, 2023; Le Monde, 2022). By 2022, public protests in Bamako and Ouagadougou erupted into calls for French troops to leave.

France’s withdrawal from Mali (2022), Burkina Faso (2023), and Niger (2023) was not a strategic redeployment—it was a forced exit (France24, 2023; The Guardian, 2023). Each ejection reflected deepening resentment toward France’s perceived imperial behavior, and a rejection of the logic that security must come from Paris.

10.3 The Alliance of Sahel States: A Bloc is Born

In response to mounting threats—internal and external—Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger formalized the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) in 2023. This was not merely a defensive military pact, but a political declaration of post-colonial autonomy (ISS Africa, 2023). For the first time in decades, three Francophone nations publicly aligned to declare their intent to control their own security apparatus, economic systems, and political trajectories, without mediation from Paris, Brussels, or Washington.

This alliance is revolutionary in its implications. It bypasses ECOWAS, which many now see as compromised by France-aligned elites, and opens the door to joint military command structures, shared economic zones, and unified diplomatic platforms (African Arguments, 2023).

As RFI (2022) reports, this is not a symbolic gesture. Coordinated border security operations have already begun, and meetings are underway to explore common trade policies. In essence, AES seeks to be an African alternative to Francafrique—one born not out of foreign strategic calculus, but of necessity, dignity, and self-reliance.

10.4 France’s Diminishing Leverage: From Bases to Backlash

France’s residual military infrastructure in Chad and Djibouti remains under increasing scrutiny. Once viewed as strategic anchors, these bases are now symbols of foreign imposition and potential liabilities for local regimes (Jeune Afrique, 2023). The public discourse across Francophone Africa has decisively shifted, and governments that host French troops now face serious legitimacy crises.

In Chad, for instance, civil society groups and opposition politicians have demanded a review of the long-standing military agreements with France. In Niger, even after the 2023 military coup, transitional authorities demanded the departure of French forces within 30 days—a move that would have been unthinkable even five years earlier (France24, 2023).

The narrative that France is a stabilizing force has collapsed. Instead, the prevailing view, as DW (2023) reports, is that France’s military presence perpetuates insecurity and obstructs sovereign solutions. With diminishing trust, France is rapidly becoming a strategic orphan in the Sahel, losing not just military partners but also moral ground.

10.5 Traoré’s Role: A Youth Icon, A Continental Symbol

Ibrahim Traoré’s rise was not just political—it was psychological. He embodies a generational rupture: a rejection of the docile Francophone leadership that long traded sovereignty for stability. Traoré speaks directly to the youth, bypassing traditional diplomatic channels and framing anti-imperial resistance as both necessary and righteous (Reuters, 2023).

His speeches echo those of Thomas Sankara, but with sharper clarity for the 21st century: the war is not just about security; it’s about identity, dignity, and economic emancipation. Traoré has insisted that security cannot be outsourced, and that African nations must stop serving as “buffer zones” for foreign wars and extractive ambitions (The Guardian, 2023).

His symbolism has spread beyond Burkina Faso. Across Mali and Niger, murals, rap songs, and university debates portray him as the face of a Pan-African renaissance. In France, his image incites unease. In Africa, it inspires unity.

10.6 The ECOWAS Question: Realignment or Irrelevance?

As Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger consolidate their new bloc, questions swirl around the future of ECOWAS, the West African economic community historically backed by France and influenced by Nigeria’s diplomatic leadership. ECOWAS’ ambiguous stance on military coups, combined with its perceived subservience to foreign interests, has eroded its credibility among AES members (Brookings Institution, 2022).

Rather than wait for reform, the Sahel bloc has chosen strategic divergence. AES is actively pursuing independent economic frameworks, joint infrastructure development, and even the formation of a shared currency—potentially replacing the CFA franc (Al Jazeera, 2023). These efforts represent a radical realignment of West African politics, centered not on Abuja or Paris, but on a new Sahelian consensus.

This reconfiguration terrifies France, not only because it diminishes its military access, but because it threatens to inspire a broader continental revolt against the logic of dependency.

10.7 What France Fears Most: Replication of the Traoré Model

France’s worst nightmare is not the loss of a single military base or mining concession. It is the viral spread of the Traoré doctrine—a template of resistance, sovereignty, and popular legitimacy that other African nations might emulate. If Guinea, Senegal, or even Côte d’Ivoire were to adopt a similar stance, the entire Francafrique architecture would implode.

This is why France has responded to Sahelian realignments not only with diplomatic scorn but with increased media propaganda, economic threats, and support for ECOWAS sanctions (RFI, 2022; BBC, 2023). But the tide appears irreversible.

The African youth, representing over 60% of the continent’s population, have found a language of defiance that no longer bends to the rhetoric of partnership and peacekeeping. The truth is out: France was not keeping peace—it was keeping power.

10.8 Conclusion: The Sahel Leads, the Continent Watches

In the crucible of resistance, a new Sahel is emerging—one that no longer seeks approval from Paris or validation from the West. Its leaders, particularly Ibrahim Traoré, have taken the bold step of declaring: “We will fight our own battles, defend our own borders, and define our own future.”

The Alliance of Sahel States is more than a security coalition; it is a philosophical rebellion, a declaration of mental, political, and strategic liberation. France, once the arbiter of African destinies, now stands at the margins, watching the house it built crumble brick by brick.

The continent is watching. And history is being rewritten—in African hands.

Part 11: Debt Diplomacy — How France Keeps Africa Chained Through Finance

11.1 The New Chains of Control

While the colonial empires of the 19th and 20th centuries relied on gunboats and governors, 21st-century imperialism is disguised in spreadsheets, aid packages, and loan agreements. France’s modern hold over many African nations is less visible than military occupation—but no less powerful. Through a web of loans, debt servicing structures, and “development aid” tied to French conditions, France has entrenched itself in African economies, continuing to extract value while presenting itself as a benefactor (The Conversation, 2022; Eurodad, 2022).