By Prof. MarkAnthony Nze

Investigative Journalist | Public Intellectual | Global Governance Analyst

“The British Empire did not simply rule Nigeria—it rewired it, embedding its logic into the economy, the law, the classroom, and the imagination.”

Executive Summary

The Long Shadow of Empire and the Urgent Call for Decolonization

This 12-part series unpacks the deep, systemic, and enduring exploitation of Nigeria by the British Empire—revealing a history not of reluctant rule, but of deliberate conquest, control, and resource extraction. From the initial economic footholds of the Royal Niger Company to the violent annexation of sovereign kingdoms like Benin and Sokoto, Britain established an empire not to civilize, but to capitalize.

Colonialism in Nigeria was orchestrated through a complex web of military dominance, administrative engineering, cultural suppression, and economic plunder. Indigenous resistance—whether through the guerrilla tactics of the Ekumeku Movement, the revolutionary leadership of Nnamdi Azikiwe, or the mass mobilization of the Aba Women’s War—was constant and courageous. Yet the British state responded with brute force, manipulation, and divide-and-rule tactics that fractured Nigerian unity.

Even after independence in 1960, the architecture of exploitation persisted. British corporations like Shell maintained a stranglehold on Nigeria’s most valuable resource—oil—while British banks, schools, and military partnerships continued to shape the country’s trajectory. Through instruments like the Commonwealth, foreign aid, education policy, and soft power diplomacy, Britain repackaged imperialism as partnership, leaving Nigeria politically free but economically and epistemically bound.

This series reveals that neo-colonialism is not a theory—it is a living, material condition. The scars of colonial education, extractive trade, and British-backed authoritarianism continue to define Nigeria’s development crisis, institutional dysfunction, and cultural identity struggles. While British officials celebrate decolonization as a past accomplishment, Nigerians live its unresolved consequences every day.

Yet, there is hope—and it lies in resistance. Nigeria’s history is not just one of exploitation, but of resilience. From nationalist movements to decolonial scholarship, Nigerians have continuously challenged imperial narratives and demanded justice. Today, this legacy endures in campaigns to return looted artefacts, reform curricula, renegotiate foreign contracts, and reject Western epistemic dominance.

The British Empire did not simply rule Nigeria—it rewired it, embedding its logic into the economy, the law, the classroom, and the imagination. Dismantling this legacy requires more than remembrance. It demands restitution, systemic reform, epistemic liberation, and a collective refusal to normalize colonial residues.

This executive summary calls on scholars, policymakers, and the public to see beyond flags and independence anniversaries. The real task of liberation lies in confronting Britain’s ongoing imperial entanglements—and building a Nigeria that is not only independent, but truly sovereign in mind, economy, and spirit.

Part 1: Introduction – A Legacy That Never Left

1.1 Introduction: Empire’s Enduring Footprint

In the sprawling and complex history of empires, few leave behind footprints as deep and damning as the British Empire. At its peak, the empire claimed dominion over nearly a quarter of the world’s landmass and population, building its strength not on noble ideals or mutual prosperity, but on calculated plunder, deception, and domination. Nowhere is this legacy more sharply illuminated than in Nigeria—a nation whose vast natural wealth, diverse cultures, and vibrant pre-colonial civilizations were reduced to tools of imperial gain. The British Empire did not merely colonize Nigeria; it exploited, corrupted, and engineered a system that continues to manipulate the country from afar under new guises and in more insidious forms.

This essay contends that British imperialism in Nigeria was not just a historical act of foreign domination—it was a meticulously structured system of resource extraction, cultural erasure, and institutional corruption. More importantly, the imperial machine did not simply disappear with the lowering of the Union Jack in 1960. It morphed, migrated, and modernized—repackaging itself into neocolonial mechanisms such as trade agreements, multinational corporate interests, and international financial institutions. These contemporary structures continue to influence and at times destabilize Nigeria’s sovereignty, mirroring the very logic of exploitation that defined colonial rule.

To truly grasp the depth of Britain’s role in shaping modern Nigeria—its divisions, its systemic corruption, its economic vulnerabilities—one must begin not with the flag-waving ceremony of independence, but with a deeper, more uncomfortable truth: the British Empire’s presence in Nigeria was never about partnership. It was about power. And that power remains, less visible perhaps, but no less damaging.

1.2 From Trade to Tyranny: The Genesis of Exploitation

The relationship between Britain and what is now Nigeria began not with governance, but with commerce—and specifically, with the transatlantic slave trade. From the 16th to the 19th century, British merchants played a central role in the capture, transport, and sale of millions of Africans, many from the territories that would later be called Nigeria. Human lives were reduced to economic units in a brutal triangular trade network that fueled British industrialization and decimated African communities. This period laid the psychological and economic groundwork for future exploitation: Africans were commodities, and African lands were warehouses waiting to be looted.

As abolition gained momentum in Britain, colonial interest did not wane—it merely adapted. The moral veneer of abolition was quickly replaced with the “civilizing mission” rhetoric, even as economic motives remained paramount. The Royal Niger Company, a mercantile corporation backed by the British government, became the de facto ruler of large parts of the Nigerian interior by the late 19th century. It imposed taxes, enforced monopolies, and deployed armed forces to crush dissent, all while funneling profits back to London. This privatized form of imperialism—where a company, not a crown, wielded power—was a forerunner to today’s global corporate exploitation, a theme we will revisit later.

1.3 The Machinery of Corruption: Governance as Control

When Nigeria was officially amalgamated into a British colony in 1914, the machinery of governance was designed not to serve the people, but to discipline them. British administrators ruled through a model of indirect rule, appointing local elites and traditional rulers as intermediaries while retaining ultimate control in colonial hands. This system sowed divisions—ethnic, religious, and regional—that were not incidental, but deliberate. By fostering mistrust and competition among groups, the British created a fractured society where unity was virtually impossible. Divide-and-rule was not a tactic; it was doctrine.

This structure institutionalized a form of corruption that persists in Nigeria today. Colonial officers encouraged Nigerian chiefs and elites to act as local enforcers in exchange for power and privilege. In doing so, they birthed a political culture rooted in patronage, exploitation, and loyalty to foreign interests rather than local constituencies. Power became transactional, governance became extractive, and justice became a service that could be bought or silenced. When independence arrived in 1960, the newly minted Nigerian elite inherited not a democratic legacy, but a colonial blueprint for personal enrichment and national neglect.

1.4 The Illusion of Independence: A New Face of Empire

Nigeria’s independence in 1960 was celebrated with much fanfare, but it was, in many ways, an illusion. While the Union Jack was lowered, British companies retained massive control over Nigeria’s key economic sectors, particularly oil and mining. Legal agreements ensured that profits continued to flow to London, not Lagos. British-trained civil servants remained embedded in Nigeria’s bureaucracy, and the education system continued to prioritize Western epistemologies while marginalizing indigenous knowledge.

This wasn’t a retreat—it was a rebranding. The empire had traded in its overt colonial symbols for corporate logos, investment treaties, and diplomatic formalities. Britain’s influence became more discreet but no less potent. Nigerian leaders who sought to challenge this system were often isolated or undermined. Those who complied were rewarded. This dynamic entrenched a post-colonial elite that functioned as domestic proxies for external interests, deepening the gulf between government and governed.

1.5 Neocolonialism and the Continuum of Exploitation

In the decades since independence, British involvement in Nigeria has shifted from territorial control to financial and economic manipulation. Through institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank—where Britain holds considerable sway—Nigeria has been subjected to structural adjustment programs that decimated public services, devalued its currency, and opened up its markets to foreign predation. These policies, often imposed as conditions for aid or debt relief, prioritized global capital over local welfare and made it nearly impossible for Nigeria to chart an autonomous economic path.

Moreover, British multinational corporations, particularly in the oil and gas sector, continue to reap enormous profits from Nigeria’s natural resources. Shell, once a British-Dutch entity and now functionally headquartered in London, has been repeatedly implicated in environmental devastation, human rights abuses, and corrupt dealings with Nigerian officials. The Niger Delta—one of the most oil-rich regions in the world—remains among the poorest and most polluted, a stark symbol of modern imperialism masquerading as foreign investment.

1.6 The Cultural Legacy: Erasure, Alienation, and Resistance

The British Empire did not merely exploit Nigeria economically and politically—it also waged war on its cultural identity. Indigenous languages were suppressed in favor of English. Traditional religious practices were ridiculed and replaced with Christian dogma. Historical narratives were rewritten to glorify colonial benevolence and obscure indigenous resilience.

This cultural colonization produced a psychological disorientation that lingers today. Nigerians often find themselves navigating a hybrid identity, caught between pride in their heritage and internalized beliefs in Western superiority. Educational curriculums still prioritize British authors and perspectives. Even the legal and political systems bear the stamp of Westminster, despite functioning in a radically different context.

Yet, resistance has always existed. From early anti-colonial warriors to today’s environmental activists, Nigerians have continuously challenged imperial domination in all its forms. But resistance alone is not enough if the global structures enabling exploitation remain intact.

1.7 Conclusion: A Nation Still Bound

The British Empire’s corruption and exploitation of Nigeria was not a historical episode—it was the opening chapter of a longer story of domination. What began with conquest and resource theft has evolved into economic dependency, cultural alienation, and political manipulation. The names have changed—from colonial governors to corporate boards, from missionary schools to foreign NGOs—but the logic remains: extract, control, profit.

Understanding this legacy is not merely an academic exercise; it is a moral and political imperative. To confront corruption and exploitation in present-day Nigeria, we must recognize that much of it is rooted in structures designed by colonial powers and sustained by global complicity. True sovereignty requires more than independence; it requires decolonization—not just of institutions, but of minds, economies, and systems of power.

As we trace this legacy across history and into the present, one truth becomes painfully clear: the British Empire never truly left Nigeria. It simply changed its clothes.

Part 2: Pre-Colonial Nigeria – A Landscape of Sovereign Power

2.1 Introduction: A Fabric Already Woven

Long before the British arrived with their imperial ambitions and mercantile guns, the territories that make up present-day Nigeria were not only inhabited but deeply organized. These lands were governed by thriving kingdoms, city-states, and confederacies with complex social, economic, and political systems. The popular colonial justification of bringing “civilization” to a “dark continent” was not only misleading—it was a deliberate erasure of centuries of indigenous governance, knowledge, and prosperity. Understanding this pre-colonial landscape is critical because it demonstrates that Nigeria was not a void waiting to be filled but a vibrant, functioning society dismantled by colonial corruption and control.

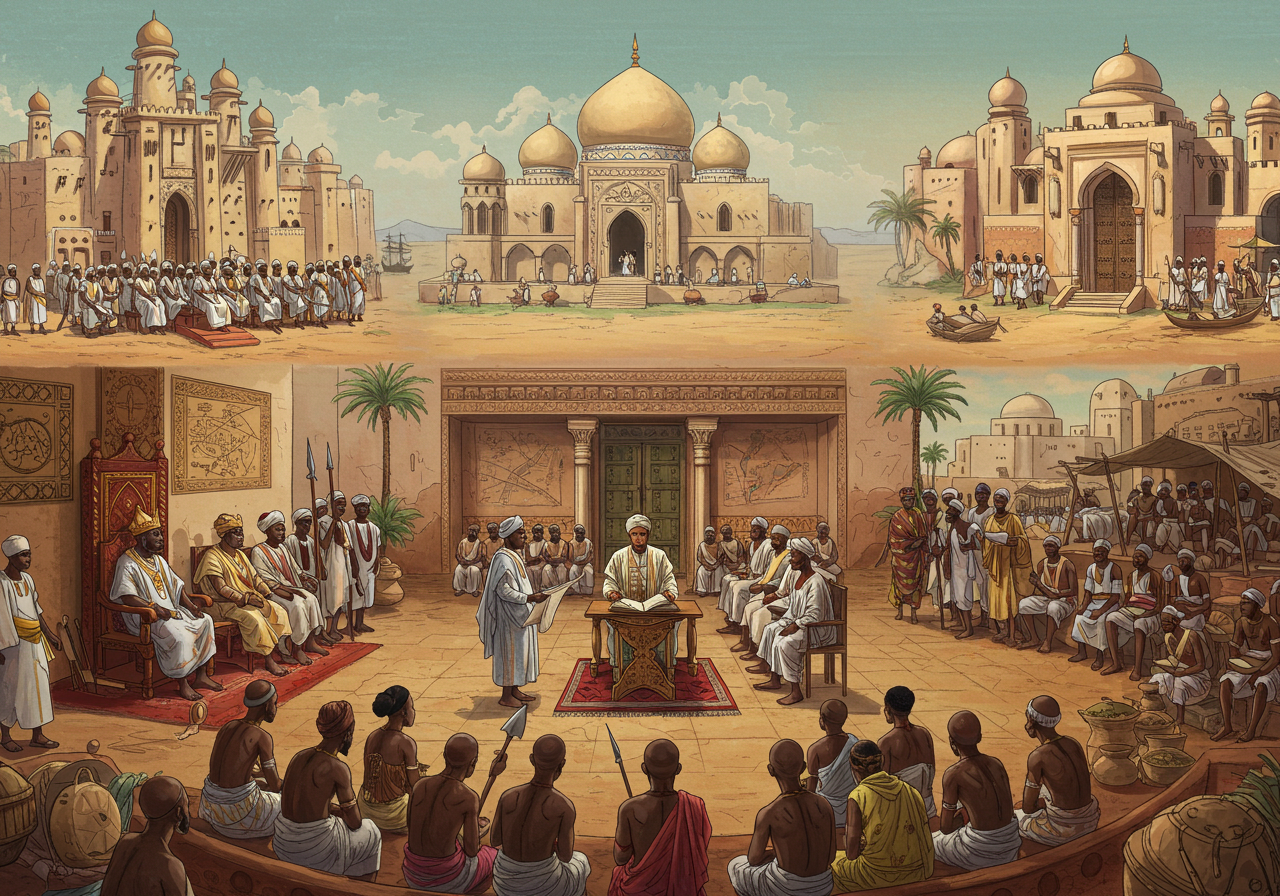

2.2 Sophisticated Political Systems and Governance

Contrary to colonial portrayals of Africa as anarchic or primitive, pre-colonial Nigeria boasted some of the most advanced political systems in sub-Saharan Africa. The Oyo Empire, for example, had a constitutional monarchy with a system of checks and balances, including the powerful council of state known as the Oyo Mesi, which could depose the king (Alaafin) if he abused his powers (Ajayi & Crowder, 1985). In the north, the Sokoto Caliphate, established by Uthman dan Fodio in the early 19th century, governed a vast territory through a decentralized network of emirates that combined Islamic law with indigenous administrative practices (Last, 1967).

These systems reflected not only political sophistication but also a recognition of governance as a social contract. Leaders were held accountable, power was distributed, and administrative structures allowed for local participation and adaptability. This reality stands in stark contrast to the British-imposed indirect rule system, which would later strip local institutions of their autonomy and weaponize them for extraction.

2.3 Economic Complexity and Regional Trade Networks

Pre-colonial Nigerian economies were far from stagnant. Trade was extensive, both within and beyond the region. The Hausa city-states, located along trans-Saharan trade routes, had established commercial links with North Africa, exchanging leather goods, textiles, kola nuts, and slaves for salt, books, and other goods (Falola & Heaton, 2008). In the forest zones of southern Nigeria, the Kingdom of Benin developed a sophisticated bronze and ivory industry, which was highly prized across West Africa and even in parts of Europe before direct colonization (Ryder, 1969).

In fact, archaeological findings in the Nok region of present-day central Nigeria reveal iron-smelting technology dating back to 500 BCE—predating many European metallurgical developments (Shaw, 1978). Markets were central to daily life and often governed by guilds or local institutions that regulated prices, ensured quality, and maintained peace (Lovejoy, 1980).

These economic structures illustrate a degree of financial self-reliance that was later disrupted by colonial intervention. British colonial authorities did not expand or support indigenous economies—they repurposed them to serve British industrial interests, extracting raw materials while underdeveloping domestic industries (Rodney, 1972).

2.4 Cultural and Intellectual Flourishing

Nigeria’s pre-colonial societies were also vibrant cultural and intellectual hubs. In the Sokoto Caliphate, Islamic scholarship flourished, with centers such as Kano and Katsina producing legal, theological, and philosophical texts in Arabic and Ajami (Hausa written in Arabic script) (Boyd & Mack, 1997). In the south, the Ife and Benin Kingdoms developed highly advanced artistic traditions, most famously the Ife heads and Benin bronzes, which demonstrated a mastery of metallurgy, symmetry, and realism comparable to Renaissance Europe (Dark, 1973).

These achievements were not simply decorative. Art, literature, and oral traditions served as tools of history-making, diplomacy, and political messaging. The cultural self-confidence of these societies challenges the colonial trope of a blank-slate Africa. In fact, Britain’s later pillaging of Nigerian artifacts—many of which still reside in British museums—was both an act of material theft and cultural suppression (Hicks, 2020).

2.5 Religious Pluralism and Social Harmony

Religious practices in pre-colonial Nigeria were diverse and often coexisted peacefully. While Islam spread through the northern emirates and Christianity began to arrive via Portuguese traders in the south, indigenous religions—rooted in animism, ancestral worship, and cosmology—remained dominant. These systems emphasized communal ethics, environmental stewardship, and a sacred interconnectedness between the physical and spiritual realms (Peel, 2000).

British colonizers viewed these belief systems as “superstitions” to be stamped out, not as viable philosophies with complex theological underpinnings. As such, the arrival of colonial rule introduced a divisive religious binary, exacerbating tensions between Muslim and Christian communities that continue to plague Nigeria’s political landscape today (Kalu, 2008).

2.6 Social Organization and Gender Roles

Many pre-colonial Nigerian societies practiced forms of gender complementarity rather than rigid patriarchy. In Igbo communities, for instance, women held significant power through associations like the Umuada (daughters of the lineage) and market guilds, which could organize economic boycotts or sanction male leaders (Amadiume, 1987). The famous Aba Women’s War of 1929, often misrepresented as a tax protest, was in fact a sophisticated act of resistance rooted in pre-colonial traditions of female political activism.

Colonial rule introduced Victorian gender norms that undermined these structures, relegating women to the domestic sphere and excluding them from formal political participation. This colonial reshaping of gender dynamics served to weaken communal resilience and centralize authority in male-dominated systems amenable to British control (Oyěwùmí, 1997).

2.7 A False Justification for Empire

British colonial rhetoric often depicted Africa as a wilderness awaiting enlightenment—a moral justification for conquest. Yet the reality of pre-colonial Nigeria exposes this narrative as not only false, but deeply manipulative. Far from introducing governance, commerce, or culture, the British dismantled existing systems that were often more inclusive, sustainable, and locally accountable than the foreign institutions that replaced them.

As Mamdani (1996) argues, the colonial state in Africa was built not to develop but to dominate. In Nigeria’s case, it replaced consensual authority with coercion, diversified economies with monocultures, and community governance with hierarchical bureaucracy. The myth of benevolent empire crumbles under the weight of evidence showing that British rule did not bring civilization to Nigeria—it interrupted it.

2.8 Conclusion: A Stolen Beginning

Understanding Nigeria’s pre-colonial systems is essential not merely for historical completeness, but for justice. It challenges the narrative that colonialism was a necessary step in Nigeria’s development and reveals the truth: that the British Empire did not discover a blank canvas, but a tapestry of power, intellect, and culture that it proceeded to unravel for profit.

As modern Nigeria grapples with corruption, inequality, and a fractured national identity, it must reckon with the fact that many of these challenges were seeded by a colonial project that intentionally destabilized the very structures that once held Nigerian societies together. In recovering the memory of this pre-colonial strength, Nigeria can begin the process not just of healing—but of reimagining sovereignty on its own terms.

Part 3: The Tools of Infiltration – Trade, Treaties, and Treachery

3.1 Introduction: Diplomacy as Disguise

Before Nigeria became a formal colony of the British Empire, its sovereignty was steadily and systematically eroded by imperial strategies that masked aggression under diplomacy. These strategies relied not on direct warfare but on calculated trade policies, manipulated treaties, and cultural penetration through soft power. The British did not immediately conquer Nigeria through sheer force; instead, they gained influence through deception, coercion, and monopolistic capitalism. What followed was the construction of an imperial web that transformed commerce into control, negotiation into nullification of sovereignty, and diplomacy into a tool of dominion.

3.2 Commercial Entry as Imperial Beachhead

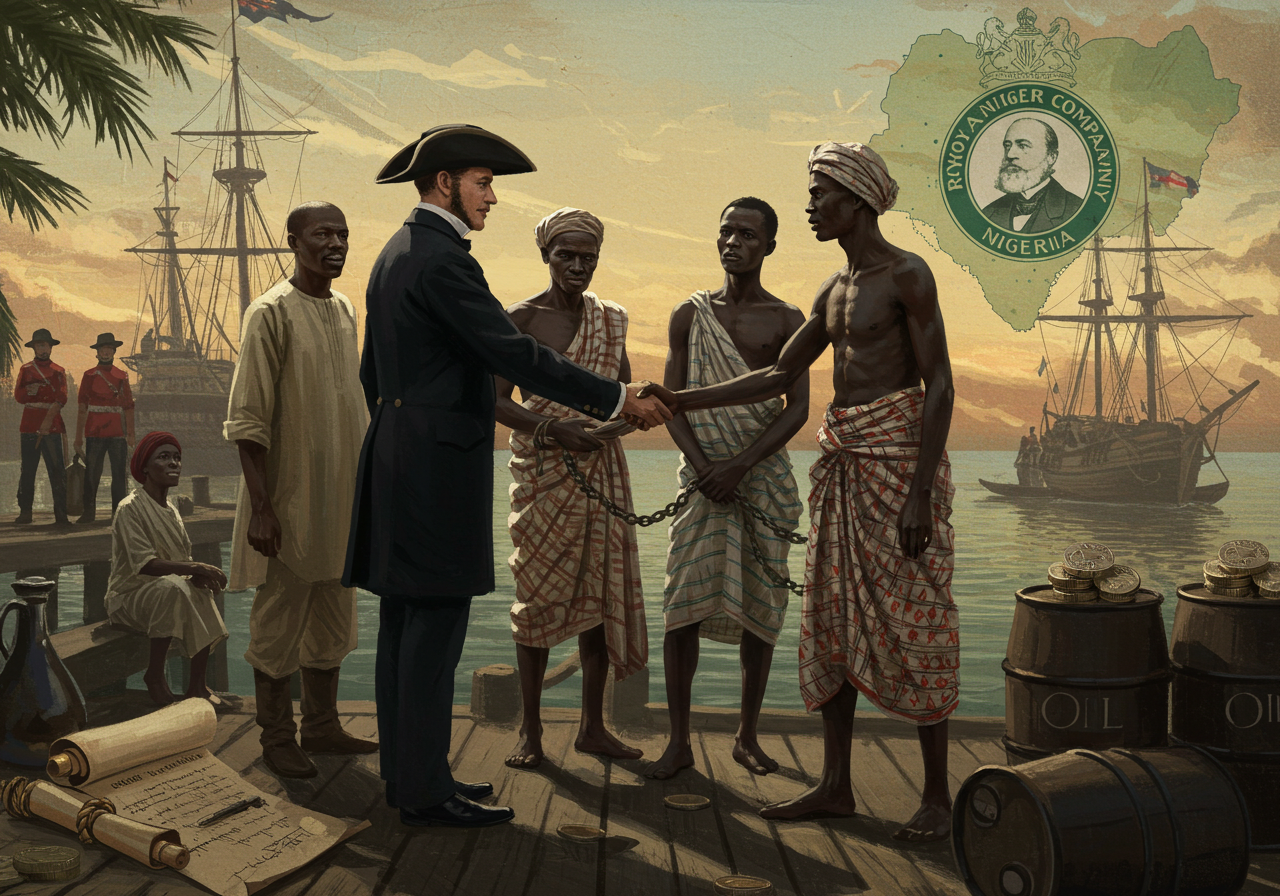

The initial entry of Britain into what is now Nigeria was commercial rather than political. By the mid-19th century, British traders had begun consolidating control over palm oil and other key exports from the Niger Delta, under the guise of promoting “legitimate trade” after the abolition of the slave trade (Falola & Heaton, 2020). However, this trade was not open or equal. British merchants, backed by the Royal Navy, established exclusive trading posts, often eliminating indigenous competition and forcing chiefs into unequal partnerships.

One of the key instruments of this economic takeover was the Royal Niger Company, chartered in 1886. The company, led by Sir George Goldie, functioned essentially as a private government, with powers to negotiate treaties, raise militias, and collect taxes (Lawal, 2021). This merger of private capital and imperial authority laid the foundation for Britain’s full political control over Nigeria by the turn of the century.

3.3 Treaty Diplomacy: Contracts of Coercion

One of the most insidious tactics employed by the British in this phase was the use of treaties—often signed under duress or with deceptive terms. Local rulers, in many cases unfamiliar with European legal norms or unable to read English, were pressured or tricked into signing documents that effectively ceded political and economic sovereignty (Njoku, 2021).

The Treaty of Cession of Lagos in 1861 is a vivid example. Oba Dosunmu of Lagos signed the treaty while British warships threatened bombardment of the city. Though presented as a diplomatic agreement, it was, in effect, an act of blackmail that turned Lagos into a British colony (Ogbogu, 2022).

Scholars have argued that such treaties were constructed not to reflect genuine consent but to provide Britain with a legal façade to justify colonisation before European rivals and the international community (Ezeani, 2023). These treaties often included vaguely worded clauses that transferred ambiguous “protection” into complete administrative control.

3.4 Corporate Colonialism and the Royal Niger Company

The Royal Niger Company (RNC) was central to Britain’s early infiltration. It signed over 400 treaties with local leaders, many of whom later protested that they had been misled or coerced. The RNC created monopolies on palm oil and other key exports, drastically underpaying local producers while amassing enormous profits (Smith, 2021).

Under the guise of economic development, the company enforced price controls, outlawed competition, and used armed force to suppress dissent. For example, the 1895 Brass War saw the RNC’s military forces crush the Nembe people of the Niger Delta who resisted economic strangulation (Udo, 2020). The company’s actions served as a precursor to the colonial state’s broader approach: extractive, coercive, and dismissive of indigenous authority.

3.5 Divide-and-Conquer Tactics

Ethnic and political fragmentation became a strategic tool for Britain’s early imperial ambitions. By negotiating separate treaties with rival leaders and factions within the same regions, the British undermined efforts at regional unity and exploited long-standing tensions.

For instance, in the Niger Delta, the British alternated alliances between the Itsekiri, Urhobo, and Ijaw groups, manipulating each against the other to secure trade advantages and political leverage (Okonkwo & Abiola, 2022). In the north, the British engaged directly with the Sokoto Caliphate and the Emirate system, offering conditional autonomy in exchange for acceptance of British authority—a policy that would later evolve into indirect rule (Abubakar & Mustapha, 2021).

These diplomatic strategies deliberately disrupted pre-existing networks of cooperation and sowed divisions that continued into Nigeria’s post-independence era.

3.6 The Language of “Protection”

British agents often used the language of “protection” to mask imperial ambition. Chiefs were promised military assistance or political support in return for ceding trade rights and political control. Yet this protection often meant little more than domination. As soon as treaties were signed, British representatives demanded tribute, imposed new taxes, and dismantled local governance structures (Onuoha, 2023).

This strategy was particularly effective in frontier areas like the Middle Belt, where smaller polities sought security from more powerful neighbors. British officials exploited this vulnerability to insert themselves as arbitrators, only to gradually take over the administrative and legal systems of the region (Aluko, 2020).

3.7 Missionaries as Instruments of Influence

While traders and treaty-makers advanced economic and political goals, Christian missionaries played a subtler but equally significant role. The Church Missionary Society and other Christian groups introduced Western education and literacy—tools that helped shape the cultural and ideological alignment of local elites (Chinweuba & Olukoya, 2021). Mission schools taught British history, values, and language, fostering a generation of Anglicized Africans who would become intermediaries for colonial administration.

Though many missionaries had sincere humanitarian motives, their activities often prepared the ground for deeper British penetration. The erosion of indigenous belief systems and the elevation of Western epistemologies made colonial domination appear natural and even desirable in the eyes of some local converts (Adewale, 2023).

3.8 Transition to Formal Colonial Rule

By 1900, Britain formally assumed control over territories previously governed by the Royal Niger Company, compensating the company with £865,000 (roughly £100 million today) for its loss of charter (Lawal, 2021). This transition was not the beginning of British control but a formalization of a system that had already been embedded through treaties, trade monopolies, and missionary influence.

Frederick Lugard, who became High Commissioner of the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria, simply extended the infrastructure already built by the RNC. The tools of infiltration had completed their purpose: Nigeria was not just militarily annexed—it was economically and ideologically captured.

3.9 Conclusion: A Nation Bought Before It Was Conquered

The British Empire did not need to fight a full-scale war to dominate Nigeria. It achieved control through strategic trade monopolies, coercive treaties, and cultural manipulation. The use of legal contracts, commercial ventures, and missionary activities as instruments of empire reveals how deeply entrenched imperial ambition was in every British action during the pre-colonial period.

These tools of infiltration laid the foundation for the systemic exploitation that followed. More importantly, they disrupted indigenous structures of governance, trade, and culture in ways that continue to haunt Nigeria today. The legacy of these tactics is not just historical—it is institutional, woven into Nigeria’s political and economic systems, from its trade dependencies to its fractured national identity.

Britain may have planted its flag in Nigeria in 1900, but it had already claimed the country—through ink, not blood—long before that.

Part 4: The Royal Niger Company – Corporate Colonialism and the Foundations of Exploitation

4.1 Introduction: Empire by Enterprise

When the story of Nigeria’s colonization is told, the emphasis often rests on British governmental forces and formal imperial administration. However, long before Nigeria was declared a protectorate, an entity with no democratic legitimacy was already ruling significant parts of the territory—The Royal Niger Company (RNC). Backed by the British Crown, the RNC was not just a trading organization but a state in everything but name: it signed treaties, collected taxes, operated private armies, and enforced monopolies.

This section explores how the Royal Niger Company institutionalized economic exploitation, legalized plunder, and laid the foundation for the systemic corruption that would define British colonial rule in Nigeria. It highlights how corporate imperialism operated not only as a business model but as a proto-colonial state, prioritizing profit over people and expansion over ethics.

4.2 Corporate Power with Imperial Backing

Established in 1886 under the leadership of Sir George Goldie, the Royal Niger Company was a direct product of British capitalist expansionism. It was created from the merger of competing British trading firms in the Niger Basin, unified under the National African Company, which eventually received a Royal Charter—effectively granting it the powers of a government (Lawal, 2021). The Company’s authority extended over what would become Northern Nigeria, with its headquarters in Lokoja.

The Charter allowed the RNC to sign treaties with indigenous leaders, levy customs duties, administer justice, and maintain armed forces. In practice, this meant the RNC could operate independently of parliamentary oversight while enjoying the military and diplomatic protection of the British Crown (Smith, 2021). It was a prototype for modern corporate neocolonialism: an enterprise with extraordinary extraterritorial powers operating for imperial profit under the camouflage of commerce.

4.3 Treaties of Coercion and Legal Fictions

Between 1884 and 1898, the RNC secured over 400 treaties with local rulers along the Niger and Benue Rivers. These treaties, typically written in English and couched in deliberately vague legal terms, were often misunderstood—or outright mistranslated—by local chiefs (Njoku, 2021). In exchange for trivial gifts—such as gin, mirrors, or uniforms—rulers signed away their sovereignty, trade rights, and land.

For instance, a typical clause read: “The chief cedes forever the whole of his territory to the Company… with full rights of jurisdiction, administration, and taxation.” In many cases, rulers believed they were merely establishing trade partnerships or securing protection against rival groups (Ezeani, 2023).

This exploitation of linguistic and cultural differences was a deliberate tactic. As Onuoha (2023) notes, these treaties were legal instruments of dispossession, not diplomatic agreements. They were written not to record consent but to justify conquest in the eyes of British law and European competitors.

4.4 Monopoly and Economic Suppression

One of the core goals of the RNC was to secure a monopoly over palm oil, then a vital industrial lubricant for British machinery. Once treaties were signed, the Company enforced exclusive rights to purchase goods at severely deflated prices. Local producers were prohibited from selling to competitors—particularly French or German traders—or from setting their own prices (Falola & Heaton, 2020).

Those who resisted were labeled criminals or rebels and faced military reprisals. This included economic blockades, destruction of villages, and seizure of goods. In 1895, the Nembe-Bassambiri people of the Niger Delta attacked the RNC headquarters at Akassa after years of price suppression and trade restrictions. The British responded by launching a full-scale retaliatory expedition that razed Nembe town and killed hundreds (Okonkwo & Abiola, 2022).

The message was clear: economic resistance would be met with violent suppression.

4.5 Militarized Capitalism

The RNC maintained a private armed force composed of British officers and West African mercenaries. This militia enforced trade monopolies, collected taxes, and defended Company territory. According to Smith (2021), the Company’s private army conducted more than 30 punitive expeditions between 1885 and 1899. These campaigns were framed as pacification but were, in reality, mechanisms to protect profit margins and suppress local opposition.

Unlike state-led military operations, the RNC’s campaigns were not subject to parliamentary debate or public scrutiny. The Company exercised power in a legal grey zone—backed by the British Navy when necessary but largely free from moral accountability.

This corporate militarization blurred the line between commerce and conquest. The aim was not to stabilize the region for mutual development but to create a secure trade environment for unilateral British enrichment (Adewale, 2023).

4.6 Taxation Without Representation

In territories under its control, the RNC implemented taxation policies without consultation with local leaders. The most infamous was the head tax, a flat fee levied per adult male, regardless of income or social status. This tax forced many communities into debt and created widespread resentment.

The funds collected rarely contributed to local development. Instead, they were used to fund military campaigns or repatriated to Britain to satisfy shareholders (Lawal, 2021). This system resembled modern extractive regimes where corporate profits are prioritized over local welfare.

4.7 Collapse and Transition to Crown Rule

By the late 1890s, the RNC was facing increasing resistance—both from Nigerian communities and from rival European powers. The Berlin Conference (1884–85) had formalized the “Scramble for Africa,” and Britain needed to establish direct state control to ward off German and French claims.

In 1900, the British government revoked the Royal Charter and assumed administrative control over the Company’s territories. The RNC was compensated with £865,000 (equivalent to over £100 million today), and its assets were transferred to the newly formed Protectorate of Northern Nigeria under Sir Frederick Lugard (Abubakar & Mustapha, 2021).

This transition did not end exploitation—it nationalized it. The exploitative systems built by the Company were adopted wholesale by the colonial state, including indirect rule, forced labor, and economic extraction. The RNC had simply prepared the ground.

4.8 Corporate Imperialism and Modern Parallels

The Royal Niger Company’s legacy extends beyond history. It was one of the earliest examples of corporate imperialism, a system where private interests are empowered to govern, exploit, and extract under state patronage. The model it pioneered—outsourcing empire to business—can be seen today in multinational corporations operating in Africa’s oil, mining, and agricultural sectors (Chinweuba & Olukoya, 2021).

Contemporary firms like Shell and Glencore, which dominate resource extraction in Nigeria and elsewhere, continue to operate within systems that prioritize shareholder value over local development. Just like the RNC, their operations are often protected by diplomatic relationships, legal loopholes, and weak regulatory environments (Akinola & Udo, 2022).

4.9 Conclusion: A Nation Leased for Profit

The Royal Niger Company represents one of the most egregious examples of capitalism weaponized as empire. It functioned with the full backing of the British state but without the ethical or legal constraints of governance. In the name of trade, it dispossessed, repressed, and impoverished. In the name of treaties, it erased sovereignty. In the name of development, it laid the groundwork for economic dependency.

Understanding this corporate colonization is essential to decoding Nigeria’s modern challenges—from resource dependency to institutional corruption. The RNC did not just extract resources; it extracted power from the people and handed it to institutions built on exclusion and exploitation. What followed was not accidental—it was a direct extension of a system built for profit, not people.

Part 5: Conquest and Control – Military Occupation and the Brutal Machinery of British Expansion

5.1 Introduction: The Final Push for Domination

By the dawn of the 20th century, Britain had successfully entrenched itself in the economic and political affairs of what would become Nigeria. However, where commerce and diplomacy failed to ensure full control, the British Empire turned to open military conquest. The annexation of Nigerian territories was not a defensive measure—it was a systematic campaign of violent domination. While earlier imperial efforts had masked themselves in treaties and trade, the final push for colonial consolidation was driven by gunboats, scorched-earth policies, and the strategic destruction of indigenous institutions.

This section explores how military conquest completed Britain’s imperial project in Nigeria, revealing how violence, suppression, and forced submission shaped the country’s colonial structure and long-term instability.

5.2 The Context of Conquest: Scramble and Sovereignty

The late 19th century was dominated by the Scramble for Africa, formalized at the Berlin Conference (1884–85). European empires raced to secure territories under the guise of civilizing missions and free trade. For Britain, consolidating its influence in the Niger region required not just treaties but outright occupation. The failure of the Royal Niger Company to suppress widespread resistance and increasing pressure from European rivals forced Britain to assume direct control in 1900 (Falola & Heaton, 2020).

As Akinrinade (2020) argues, Britain’s conquest of Nigeria was not a spontaneous military campaign, but a meticulously planned exercise in imperial expansion that utilized military superiority to overcome local governance systems and economic autonomy.

5.3 Northern Nigeria: Subduing the Sokoto Caliphate

In Northern Nigeria, British conquest targeted the Sokoto Caliphate, a vast Islamic empire that had governed through a decentralized emirate system since the early 19th century. Although the Caliphate had entered into limited diplomatic engagements with Britain, it remained wary of British intentions and refused to cede sovereignty.

Frederick Lugard, then High Commissioner of the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria, initiated a series of military campaigns beginning in 1902. Using African soldiers under British command, Lugard captured Kano in 1903 and forced the Sultan of Sokoto to surrender shortly after (Shokpeka & Nwaokocha, 2020).

The emirate system was not abolished, however. Instead, Britain introduced its famed “indirect rule”, co-opting emirs to administer the colony under British oversight. While this preserved certain cultural structures, it entrenched hierarchical systems and ensured loyalty to the colonial regime rather than indigenous communities (Osaghae, 2021).

5.4 Southern Nigeria: Punitive Expeditions and Cultural Destruction

While the north saw relatively centralized conquest, Southern Nigeria required piecemeal suppression of diverse ethnic groups and polities. British forces employed “punitive expeditions”—a euphemism for violent retribution against communities that resisted British economic and political control.

One of the most infamous examples is the Benin Expedition of 1897. After a group of British officials was ambushed near Benin City, the British launched a full-scale invasion, razed the city, exiled Oba Ovonramwen, and looted thousands of cultural artifacts, including the famed Benin Bronzes (Hicks, 2020). These artifacts remain central to global debates about colonial plunder and cultural restitution.

As Ikime (2021) notes, British justifications for such invasions—usually couched in terms of stopping “barbaric practices”—obscured their real motivations: to dismantle sovereign power structures that blocked British access to trade routes and resources.

5.5 The Aro Expedition and the Igbo Resistance

Another major campaign was the Aro Expedition of 1901–1902, aimed at dismantling the influence of the Arochukwu oracle and its vast spiritual-political network across Igboland. The British deemed the oracle a threat to their authority because it was a unifying symbol for resistance among the decentralized Igbo communities (Njoku, 2022).

British troops attacked Arochukwu, destroyed the shrine, and established colonial posts in the region. The expedition enabled Britain to break Igbo resistance and facilitate administrative annexation. However, the use of brute force deepened mistrust between colonial authorities and local populations—tensions that persisted long after independence.

5.6 Technology and Psychological Warfare

British military superiority stemmed from more than troop numbers. The use of advanced weapons—especially Maxim guns—gave British forces overwhelming firepower compared to spears, swords, and muskets wielded by indigenous fighters. This technological imbalance enabled the British to devastate entire communities in a matter of days.

Olatunji (2023) emphasizes that the psychological effect of this violence was as significant as its physical toll. Villages were burned, leaders executed, and symbolic institutions desecrated—all as a message that resistance would result in collective punishment. These tactics did not just suppress dissent—they aimed to break the will of resistance itself.

5.7 Guerrilla Movements and Continued Resistance

Despite British claims of “pacification,” many Nigerians resisted colonial occupation long after formal conquest. In the west, the Ekumeku Movement waged guerrilla warfare against British posts from 1898 to 1914, using the forests of Anioma as tactical cover (Okonkwo, 2020). In the north, small uprisings continued among Fulani communities disillusioned with colonial interference in Islamic law and land rights.

These rebellions were often brutally suppressed, but they demonstrated that colonization was never universally accepted. The narrative of a passive Nigeria falling willingly into British hands is a colonial myth designed to sanitize imperial violence.

5.8 The Role of ‘Pacification’ in State Formation

Once resistance was quelled, Britain moved to consolidate power. It introduced administrative divisions, appointed colonial officers, and imposed tax systems to fund the occupation. The most infamous of these was the head tax, which sparked further revolts—most notably the Aba Women’s War of 1929, where thousands of women protested colonial taxation and political marginalization (Amadiume, 2020).

These systems transformed Nigeria from a mosaic of autonomous societies into a colony unified not by culture or consent, but by violent centralization. The artificial borders and ethnic tensions created during this period continue to undermine national cohesion in postcolonial Nigeria (Osaghae, 2021).

5.9 Conclusion: Nigeria Conquered at Gunpoint

The British conquest of Nigeria was neither a noble endeavor nor a reluctant assumption of responsibility. It was a calculated military campaign driven by imperial ambition and executed with cold efficiency. From Benin to Sokoto, from Arochukwu to Ekumeku, British forces imposed colonial order by annihilating resistance and replacing it with a hierarchy of collaborators and administrators.

This conquest laid the foundation for Nigeria’s colonial state: centralized, coercive, extractive, and fundamentally disconnected from the people it governed. It also embedded patterns of authoritarianism, militarism, and ethnic division that would haunt Nigeria long after independence. Understanding this violent origin is crucial to confronting the ongoing consequences of empire—and dismantling the myths that continue to protect it.

Part 6: Divide and Rule – Engineering Fragmentation in Colonial Nigeria

6.1 Introduction: Divide to Conquer

The British conquest of Nigeria was not only military and economic—it was psychological and political. After violently subduing indigenous resistance, the British did not seek to unify Nigeria in any genuine sense. Instead, they introduced and institutionalized a policy that would define Nigeria’s colonial and post-colonial identity: divide and rule. Rather than confront the logistical complexity of managing a vast and diverse territory, Britain strategically fragmented it, exploiting ethnic, linguistic, and religious divisions to maintain control.

This section explores how British colonial administrators engineered and entrenched divisions among Nigerians, not merely as a by-product of imperialism, but as a deliberate policy to weaken resistance, suppress unity, and preserve imperial dominance. The legacy of this fragmentation—ethnic tensions, unequal development, political instability—continues to shape Nigeria’s trajectory more than a century later.

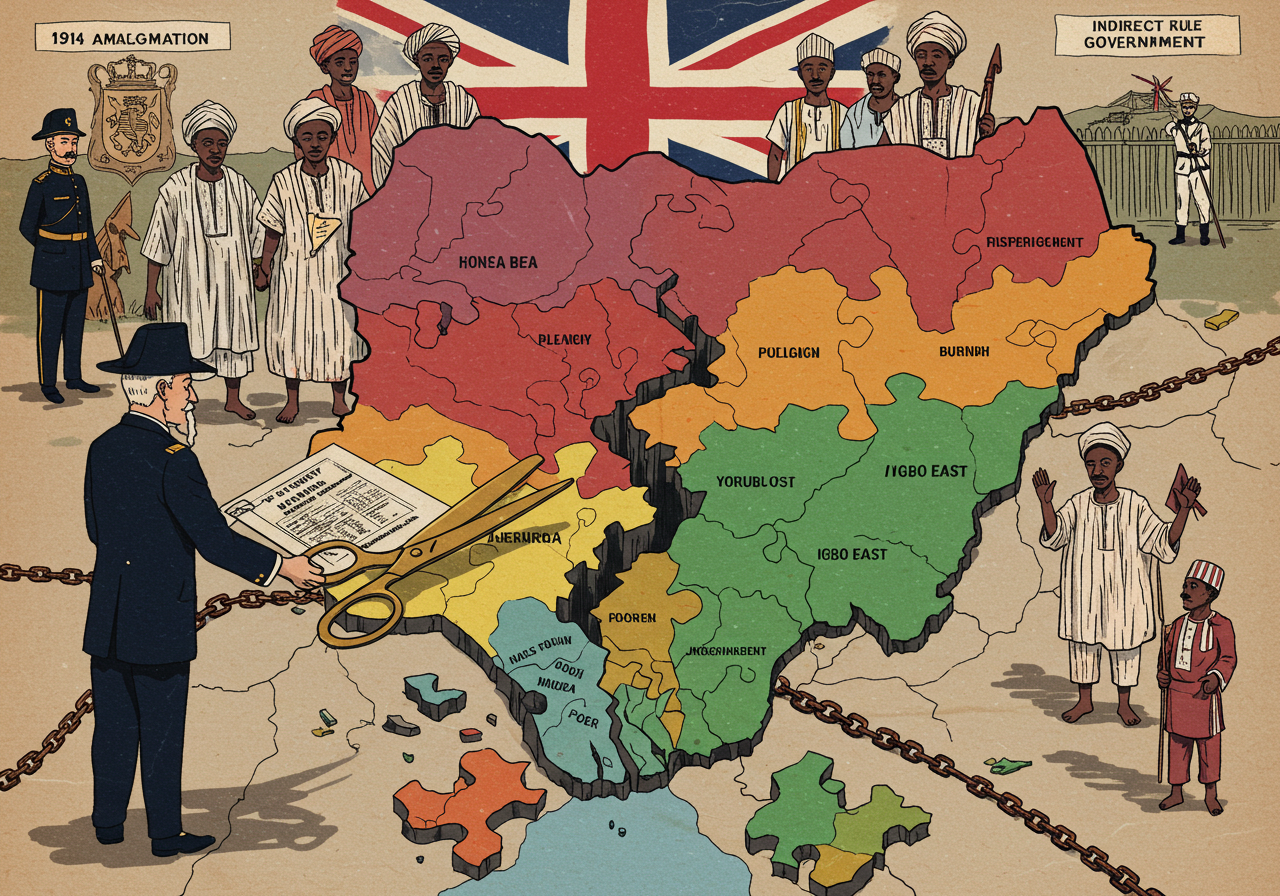

6.2 The Colonial Construction of ‘Nigeria’

Nigeria, as a nation-state, did not exist before colonization. What became Nigeria was a geopolitical invention—a forced amalgamation of over 250 ethnic groups, numerous religious traditions, and vastly different political systems. The 1914 amalgamation of the Northern and Southern Protectorates was not the result of organic unity but an administrative cost-saving decision by Lord Lugard, aimed at using Southern revenues to subsidize the North (Falola & Heaton, 2020).

According to Akinyemi (2022), the British made little effort to create national cohesion. Instead, they ruled the Northern, Western, and Eastern regions as discrete units, with separate legal systems, administrative hierarchies, and education policies. The result was a deeply balkanized colonial state where shared national consciousness was nearly impossible to develop.

6.3 Indirect Rule: Decentralized Control, Centralized Power

The core instrument of Britain’s divide-and-rule policy in Nigeria was indirect rule. Introduced by Lugard in the North and later extended to other regions, indirect rule relied on traditional rulers to govern on behalf of the colonial state. However, the system was applied inconsistently across regions.

In the Muslim North, where emirates had centralized authority, indirect rule reinforced pre-existing structures. Emirs retained significant power, including control over taxes, education, and legal matters (Shokpeka & Nwaokocha, 2020). In contrast, the Igbo-dominated East, which was organized into decentralized village republics, had no comparable centralized authority. British administrators responded by manufacturing ‘warrant chiefs’, imposing authority where none existed—leading to resentment and rebellion, including the Aba Women’s War of 1929 (Chuku, 2021).

This uneven application of indirect rule entrenched regional inequality and seeded political distrust that would explode after independence.

6.4 Ethnicization of Administration

British administrators did not view Nigerians as a unified people. Instead, colonial ethnographers categorized them into tribes, often exaggerating differences and ignoring commonalities. These ethnic categories became the basis for administrative decisions—who was appointed to office, where resources were allocated, and which regions received infrastructure investment (Udo, 2020).

The Northern region, for instance, was deliberately kept “closed” to Southern missionaries and Western education, under the pretense of preserving Islamic tradition. As a result, the South, especially the Yoruba and Igbo regions, developed faster in terms of literacy and exposure to nationalist ideas (Ikime, 2021). This educational disparity laid the groundwork for inter-regional suspicion—with Northern elites fearing Southern domination in later political processes.

British colonial officers nurtured these fears. As noted by Olatunji (2023), the colonial government often portrayed the Igbos as “aggressive,” the Yoruba as “calculating,” and the Hausa-Fulani as “loyal”—creating ethnic stereotypes that were institutionalized in colonial policy and later weaponized in post-independence politics.

6.5 The Census and the Politics of Numbers

British colonial censuses were another major tool of division. Ostensibly a demographic exercise, colonial censuses became political instruments, particularly from the 1930s onwards. Population figures were tied to representation, revenue allocation, and development planning. As such, each region sought to inflate its numbers.

According to Osaghae (2021), the colonial government encouraged this competition by refusing to establish a national identity system or centralized statistical authority. Instead, it conducted censuses regionally and inconsistently, often resulting in politically charged and contested figures. The emphasis on numbers over unity reinforced regionalism and turned ethnicity into a tool of political bargaining.

6.6 Regionalism and Educational Inequality

Britain’s education policies further deepened divisions. In the South, particularly among the Yoruba, missionary schools flourished, producing a Western-educated elite by the early 20th century. The Igbo, too, embraced education as a tool of upward mobility. By contrast, in the Muslim North, the British deliberately restricted Western-style education to prevent “political agitation,” preferring Qur’anic schools with limited secular instruction (Adewale, 2023).

This resulted in a generational literacy gap between North and South that has persisted to the present day. When Nigerians began taking over civil service roles in the 1940s and 1950s, Southerners—especially the Igbo and Yoruba—dominated, further intensifying Northern anxieties and setting the stage for future political instability (Njoku, 2022).

6.7 Divide and Rule in Economic Policy

British economic investments were also regionally skewed. The colonial government prioritized cash crop production in the South (e.g., cocoa in the West, palm oil in the East) while focusing on groundnut and cotton extraction in the North. However, transportation infrastructure like railways and roads was designed not to promote inter-regional trade or integration, but to extract resources and export them through southern ports like Lagos and Port Harcourt (Okonkwo, 2020).

The effect was an economic architecture that reinforced regional dependency on the colonial center while limiting interdependence among Nigerian regions. This fragmentation stunted the growth of a national economy and made post-independence integration far more difficult.

6.8 Divide and Rule in Nationalism and Political Mobilization

Even as nationalist movements emerged in the 1930s and 1940s, the British ensured that they remained regionally divided. Leaders such as Herbert Macaulay, Nnamdi Azikiwe, Obafemi Awolowo, and Ahmadu Bello developed strong ethnic bases and resisted alliances across regional lines.

Colonial constitutional reforms—such as the Richards Constitution of 1946 and the Macpherson Constitution of 1951—reinforced this by granting regional autonomy in a federal structure that emphasized local governance over national unity. While presented as steps toward self-government, these constitutions hardened regional identities and made cooperative governance more difficult (Falola & Heaton, 2020).

By the time Nigeria gained independence in 1960, it was already politically polarized along ethnic lines, with the three major regions dominated by three major ethnic groups. These fault lines, created and deepened by British policy, would lead to the 1966 coup, the Biafran War, and a cycle of ethnic-based politics that persists today.

6.9 Conclusion: The Empire that Fractured a Nation

British colonialism in Nigeria was not just about resource extraction or military conquest—it was about control through fragmentation. Through indirect rule, regionalized education, ethnicized administration, and selective development, Britain created a state where mistrust was structural, and unity was elusive.

The divide-and-rule policy was no accident. It was a deliberate imperial strategy—one that allowed a small number of British administrators to govern a large and diverse population by keeping it divided. In doing so, the British left behind not a united nation, but a deeply fractured one.

The long-term legacy of these divisions is evident in Nigeria’s post-colonial struggles: contested federalism, ethnic politics, regional inequality, and recurring conflict. To fully understand these modern challenges, one must reckon with the colonial project that engineered fragmentation not as failure—but as method.

Part 7: Economic Exploitation During Colonial Rule – Britain’s Engineered Underdevelopment of Nigeria

7.1 Introduction: Exploitation as Policy, Not Accident

British colonization of Nigeria was never a neutral encounter. It was not an accidental historical moment born of trade or missionary work—it was an intentional, violent project aimed at extracting economic value from a resource-rich region while embedding systems of underdevelopment. The economic policies, infrastructure design, taxation schemes, and trade mechanisms implemented during colonial rule served British interests exclusively, not Nigerian progress.

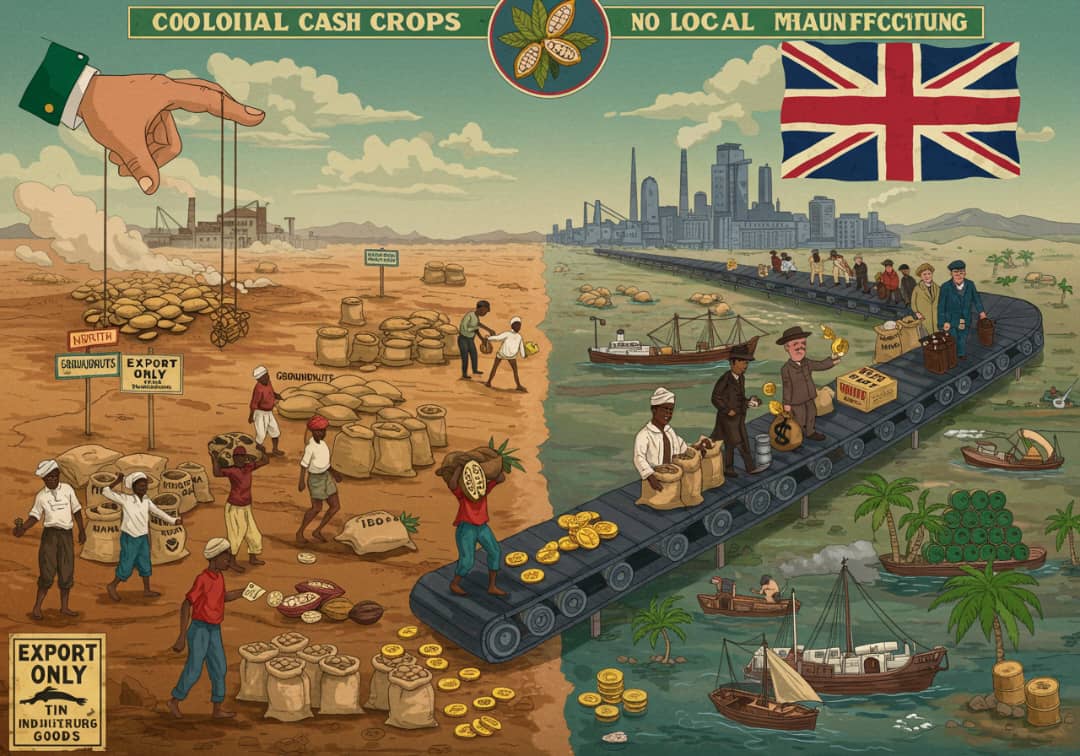

7.2 Colonial Economy: Extraction Without Industrialization

At the heart of the colonial economy in Nigeria was raw material extraction without domestic processing. Nigeria was converted into an exporter of palm oil, cocoa, groundnuts, tin, and cotton, with no encouragement for local manufacturing (Falola & Heaton, 2020).

Britain flooded Nigeria with its own manufactured goods, eliminating the space for indigenous industrial growth. This created a permanent trade imbalance, reinforcing dependency on Britain for finished products and leaving Nigeria’s economy externally oriented and structurally weak.

7.3 Monoculture and Regional Economic Fragmentation

Colonial policy entrenched cash crop monoculture:

- Groundnuts in the North

- Cocoa in the West

- Palm oil in the East

This served Britain by:

- Preventing regional economic integration

- Encouraging export dependence

- Exposing Nigeria to global price shocks

Okonkwo (2020) shows how colonial marketing boards paid below global market prices to Nigerian farmers while exporting surpluses to Britain. Njoku (2022) argues that the colonial state deliberately set price controls to suppress rural wealth accumulation.

7.4 Taxation as Exploitation: From Subsistence to Submission

British colonial taxation—poll taxes, hut taxes, income levies—was designed to force Nigerians into the cash economy, not to fund public services. Most Nigerians lived in subsistence systems with little access to currency.

As Akinyemi (2022) observes, these taxes were coercive mechanisms used to push rural populations into cash crop farming and colonial labor markets.

Direct taxation also led to major resistance movements, including the Aba Women’s War of 1929, a rebellion against both taxation and the colonial gender order (Chuku, 2021).

7.5 Labor Exploitation and Forced Work Regimes

Despite claims of humanitarian colonialism, forced labor persisted throughout British Nigeria. Known as corvée labor, it compelled Nigerians to work on:

- Railway lines

- Road construction

- Mines and plantations

The Enugu Colliery massacre of 1949—where 21 coal miners were shot for protesting wages and safety—illustrates how economic grievances were often met with lethal state violence (Adewale, 2023).

7.6 Infrastructure for Extraction, Not Development

British colonial infrastructure was export-oriented:

- Railways linked resource zones to ports, not people to opportunities.

- Roads were designed to move goods, not communities.

The Eastern Line and Western Line connected tin, coal, cocoa zones to Port Harcourt and Lagos respectively.

Olatunji (2023) notes that this infrastructure ignored local development, creating a transport network divorced from internal economic integration.

7.7 Trade Monopolies and Discriminatory Policies

Colonial Nigeria was dominated by British firms such as:

- John Holt

- United Africa Company (UAC)

- Lever Brothers

These companies enjoyed exclusive licenses, legal protections, and preferential access to land. Nigerian entrepreneurs were sidelined through:

- Discriminatory permits

- Lack of access to credit

- Colonial import-export restrictions

As Osaghae (2021) argues, the colonial economy was a rigged system, designed to benefit expatriates while excluding indigenous capitalists.

7.8 Currency and Financial Control

Nigeria’s financial sovereignty was severely compromised through the West African Currency Board (WACB), introduced in 1912:

- Nigerian currency had to be backed by British sterling, limiting liquidity.

- Nigeria’s reserves were held in London, not within local banks.

- No independent monetary policy was allowed (Udo, 2020).

This currency arrangement effectively tied Nigeria’s economy to Britain’s needs, not Nigeria’s.

7.9 Education and Economic Mobility: Limited by Design

British educational policy aimed to create clerks and interpreters, not engineers or entrepreneurs. Schools were underfunded, and the curriculum was Eurocentric.

In the North, education was even more restricted under the guise of protecting Islamic culture. In reality, it was to prevent political consciousness and resistance (Adewale, 2023).

The result was a regional literacy gap that persists, feeding into economic inequality and uneven access to government jobs (Njoku, 2022).

7.10 The Colonial Budget: Built on Inequality

Colonial Nigeria’s fiscal priorities were heavily skewed:

- Salaries of British officials consumed large portions.

- Military operations received generous funding.

- Public services such as health and education got less than 10% (Falola & Heaton, 2020).

This budgetary structure confirms that colonial policy was not developmental—it was exploitative and self-serving.

7.11 Legacy of Colonial Exploitation

The consequences of British colonial economic policy remain embedded in Nigeria’s post-independence challenges:

- Overreliance on commodity exports

- Minimal domestic manufacturing

- Infrastructure gaps

- Regional inequalities

As Osaghae (2021) argues, these are not coincidental failings, but the intended outcomes of an economic system built for imperial extraction.

7.12 Conclusion: An Empire of Extraction

British colonial rule in Nigeria was not an act of altruism—it was an empire of engineered economic underdevelopment. From forced labor and monopolized trade to taxation and infrastructural misdirection, the British created a system that:

- Extracted value without reinvestment

- Suppressed local enterprise

- Subordinated economic sovereignty

Modern Nigeria continues to grapple with this legacy. The economic roots of its present dysfunctions—resource dependency, uneven development, and fiscal vulnerability—lie in the imperial blueprint drawn by Britain.

True economic sovereignty will require not just reform, but a conscious deconstruction of colonial economic architecture.

Part 8: Corruption and Administrative Greed – Colonial Roots of Nigeria’s Governance Crisis

8.1 Introduction: Colonialism’s Hidden Currency

Corruption is often mistakenly viewed as a purely post-independence issue in Nigeria. However, this interpretation is historically narrow. The roots of systemic corruption lie in the colonial structures imposed by Britain, which introduced a governance model centered on exclusion, elitism, and impunity.

Britain didn’t invent corruption in Nigeria—but it normalized and weaponized it. This part explores how administrative greed, complicit governance, and institutional inequality were designed as tools of control, not accidental by-products.

8.2 Administrative Structure: Governance as Extraction

The British Empire ruled Nigeria through a thin layer of expatriates—fewer than 1,000 administrators for millions of people (Falola & Heaton, 2020). This forced reliance on traditional rulers and clerks created a corrupt intermediary class:

- In the South, warrant chiefs levied illegal taxes and sold justice.

- In the North, emirs exploited tax systems and appointments.

- Colonial officers ignored these abuses as long as they ensured order and revenue.

According to Osaghae (2021), the metric of success was not transparency but obedience and tribute.

8.3 Corruption by Design: The Culture of Complicity

British officials knew their system was corrupt—and allowed it. They viewed corruption not as dysfunction, but a mechanism of control. Chiefs and administrators who kept taxes flowing and rebellions suppressed were allowed to embezzle, extort, and mismanage (Njoku, 2022).

British records were sanitized. Allegations against officials or loyal elites were quietly dismissed. This institutionalized a culture of complicity, where accountability was optional and impunity expected. Misgovernance was simply the cost of stability.

8.4 Colonial Elites and Patronage Networks

Britain created a local elite class—Western-educated, mission-trained, and English-speaking. These elites were gatekeepers to power and privilege, but access to this class was highly restricted.

Akinyemi (2022) notes that employment and education were doled out along ethnic and religious lines, favoring Christians, Southerners, and loyalists. Elites quickly learned to trade loyalty for privilege. Patronage was not corruption—it was currency.

8.5 Land and Resource Mismanagement

The colonial state declared most land Crown property, allowing British officials to allocate land to companies or allies without compensation.

- In Jos and Enugu, minerals were seized while locals were displaced.

- In the Niger Delta, chiefs were bribed to sign contracts with Shell and BP (Okonkwo, 2020).

This corrupt land economy laid the foundation for post-independence oil theft, land grabs, and elite capture of resources.

8.6 The Colonial Judiciary: Law as an Instrument of Power

In theory, colonial law aimed to unify Nigeria under a modern legal system. In practice, it served empire, not justice:

- Urban centers had formal courts.

- Rural areas had “native courts”, often led by corrupt, untrained chiefs.

- Bribery, nepotism, and biased rulings were common (Shokpeka & Nwaokocha, 2020).

- British officers rarely intervened unless British interests were harmed.

The 1916 Native Administration Ordinance shielded colonial officials from legal challenges, placing them above the law.

8.7 Colonial Budgeting and Misallocation of Resources

Colonial budgeting prioritized imperial needs:

- Salaries for British expatriates

- Colonial police and military

- Infrastructure for export (railroads, ports)

Social sectors—health, education—were severely underfunded. Udo (2020) shows education often received less than 5% of colonial budgets.

This fiscal neglect incentivized local corruption. Chiefs and clerks created “customary fees,” turning state service into personal enterprise.

8.8 Elections and Early Political Corruption

With moves toward self-rule in the 1940s and 1950s, Britain introduced selective electoral politics. But these reforms were tightly controlled.

- Political parties learned to buy votes, bribe chiefs, and intimidate rivals.

- Britain supported “moderates” and discredited radicals (Osaghae, 2021).

Politics became about access to state wealth, not ideology. The corrupt administrative tactics of the colonial state were now being replicated in the name of democracy.

8.9 Institutionalizing Impunity: The Crown Above the Colony

British officials operated under full immunity. Even when caught abusing power, they were shielded by law and diplomacy.

This taught Nigerian administrators that power equals impunity. Adewale (2023) argues that this precedent shaped Nigeria’s kleptocratic post-independence culture, where elites are rarely held accountable.

The lesson learned was simple: those who serve power can serve themselves.

8.10 Continuity After Independence: Colonialism Never Left

Nigeria’s 1960 independence did not dismantle colonial governance—it inherited it:

- Civil service retained opaque processes

- Judiciary kept colonial legal codes

- Politicians practiced divide-and-rule, electoral fraud, and patronage

- Economic structures still privileged foreign companies

Njoku (2022) emphasizes that corruption in Nigeria is not a deviation, but the natural extension of a system built on control through exclusion.

8.11 Conclusion: Empire’s Most Enduring Legacy

British colonialism in Nigeria was never about good governance—it was about control, compliance, and capital. Corruption was the method, not the flaw.

- Governance was unaccountable

- Justice was selective

- Institutions served the powerful, not the people

Today’s corruption in Nigeria cannot be understood—or defeated—without confronting its colonial genealogy. The British Empire didn’t teach Nigeria how to build a state. It taught it how to rule without responsibility.

That may be the empire’s most enduring and damaging legacy

Read also: Nigeria: Corruption, Collapse, And The Crisis Under Tinubu

Part 9: Cultural and Educational Suppression – Colonialism’s War on Nigerian Identity

9.1 Introduction: The Empire of the Mind

While much of British colonization focused on land, labor, and natural resources, one of its most lasting and insidious weapons was cultural domination. The British Empire not only conquered Nigeria’s geography—it sought to remake Nigerian identity, marginalizing indigenous knowledge, languages, religions, and values.

This part explores the systematic suppression of Nigeria’s intellectual and cultural foundations and how colonialism waged a psychological war that persists long after independence.

9.2 The Assault on Indigenous Knowledge and Language

Pre-colonial Nigeria was home to rich oral traditions, complex languages, legal codes, and indigenous philosophies. The British dismissed these as “primitive” (Falola & Heaton, 2020), replacing them with English as the dominant language in education, religion, and governance.

Punishment for speaking native languages in schools and exclusion of Nigerian content from curricula severed cultural continuity. As Adewale (2023) notes, this deliberate epistemicide detached generations from their ancestral worldviews and implanted a belief in the superiority of Western knowledge.

9.3 Christian Missions and Cultural Conversion

Missionary education became the vehicle for cultural erasure. Churches portrayed African religions as demonic, customs as uncivilized, and names as shameful. Converts were encouraged to adopt European dress, names, and lifestyles.

Njoku (2022) argues that Christianity offered social and political mobility, aligning converts with colonial authority. However, it also bred identity fragmentation, where allegiance to ancestry clashed with loyalty to empire.

9.4 Educational Control and Intellectual Dependency

The colonial education system had a clear agenda: to produce obedient, Westernized clerks, not critical thinkers or scientists. Subjects were limited to:

- English language and literature

- British geography and history

- Christian religious studies

Nigerian history, folklore, and cultural systems were excluded. Chinweuba & Olukoya (2021) contend that this created an intellectually dependent elite, literate in colonial norms but detached from indigenous knowledge. Fanon’s critique of the “black skin, white mask” rings loudly in this context.

9.5 Regional Disparities and Cultural Disintegration

In the South, missionary education spread rapidly, but at the cost of cultural displacement. In the North, British policy preserved Islamic schools but restricted secular education (Olatunji, 2023).

The result was an enduring educational and cultural gap between regions, reinforcing stereotypes of Southern radicalism and Northern conservatism. These policies deepened interregional mistrust and fragmented national identity.

9.6 The “Civilizing Mission” and Psychological Subjugation

British imperial ideology justified cultural domination under the “civilizing mission”—the belief that African societies required enlightenment. This mission devalued African aesthetics, philosophies, and lifestyles, portraying colonialism as salvation.

Akinyemi (2022) explains how this manufactured inferiority. Nigerians were conditioned to feel shame in their hair, clothing, language, and religion. This psychological colonization undermined self-worth and national pride, weakening resistance.

9.7 Censorship and Control of Cultural Expression

Colonial authorities censored newspapers, theatre, and literature that celebrated African identity or questioned imperial authority. Writers like Herbert Macaulay and later Chinua Achebe faced surveillance or harassment.

Traditional festivals were sometimes banned under public order laws. Schools were warned against promoting “tribalism,” a euphemism for suppressing indigenous stories and languages. This ensured cultural silence and submission.

9.8 Art, Artefacts, and the Looting of Cultural Heritage

British forces looted thousands of cultural artefacts during military campaigns, especially during the Benin Punitive Expedition of 1897. These treasures—Benin Bronzes, ivory masks, and royal regalia—were more than art; they were repositories of authority, memory, and spirituality (Hicks, 2020).

Okonkwo (2020) argues that this theft was cultural warfare, severing Nigeria’s link to its own history. Calls for restitution continue today but face stiff resistance from Western museums that still profit from stolen heritage.

9.9 Post-Colonial Echoes: Lingering Cultural Alienation

Even after independence, Nigeria retained a colonial educational and linguistic framework. English remained the official language, and colonial-era curricula endured. Urban youth increasingly abandon indigenous languages, while traditional rituals are marginalized or commodified.

This results in cultural insecurity—a nation unsure of its identity, often measuring progress through Western aesthetics, products, and ideals.

9.10 Resistance and Cultural Reawakening

Despite colonial suppression, Nigerians have continuously resisted. From the Aba Women’s War to the literary activism of Achebe and Soyinka, resistance took creative and political forms.

The rise of Afrobeat, Nollywood, indigenous fashion, and decolonial scholarship marks a cultural reawakening. As Chinweuba & Olukoya (2021) argue, reclaiming Nigerian identity is not mere nostalgia—it is essential for national healing, dignity, and development.

9.11 Conclusion: The Empire That Rewrote the Self

British colonialism in Nigeria was not just a seizure of land—it was a seizure of identity. Through language, religion, and education, Britain rewrote Nigerian values, reshaped its intellectual horizons, and seeded psychological dependence.

Rebuilding Nigeria requires more than economic or political reform. It requires cultural sovereignty—a national project to recover suppressed histories, revive indigenous knowledge, and resist the colonial mindset.

Only then can Nigeria move from being a post-colony to becoming a post-imperial nation, whole in identity and confident in its own cultural power.

Part 10: Resistance and Nationalist Movements – Nigeria’s Struggle Against British Imperialism

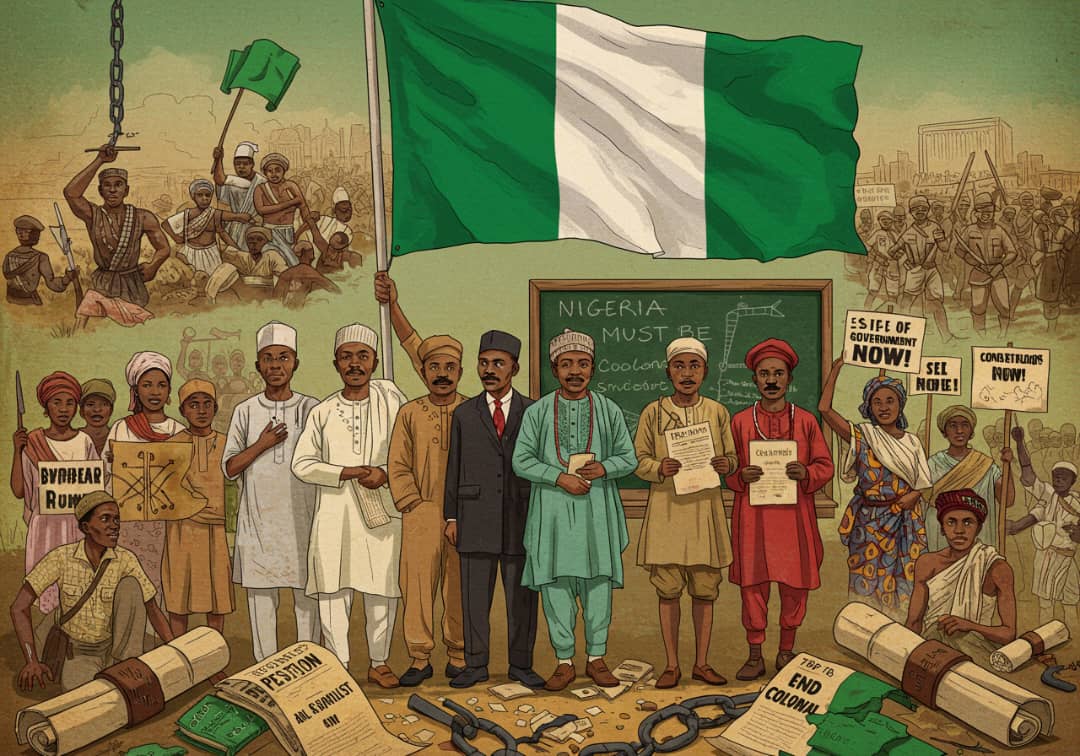

10.1 Introduction: Defiance as a Language of Liberation

From the onset of British colonial intrusion, resistance was the norm, not the exception. Nigerians did not passively accept foreign domination. Across the country, various communities employed armed rebellion, cultural defiance, intellectual protest, and political activism to contest imperial authority.

This part chronicles the evolution of Nigerian resistance, beginning with early revolts in the 19th century, escalating into mass movements and the formation of political organizations in the 20th. The narrative underscores a critical truth: Nigeria’s independence was not handed over—it was won through organized struggle and national sacrifice.

10.2 Early Resistance: Rebellion Before the Flag

10.2.1 The Akassa Raid (1895)

The Nembe Kingdom, under King Koko, challenged the Royal Niger Company’s economic monopoly and political interference in the Niger Delta. Years of exploitation, exclusion from trade, and disrespect for Nembe sovereignty culminated in a bold raid on Akassa, the company’s stronghold.

King Koko’s forces attacked and killed British personnel, seized weapons, and destroyed warehouses. In retaliation, Britain launched a naval bombardment, razed Nembe, and forced King Koko into exile.

While militarily unsuccessful, the Akassa Raid remains a pivotal moment that exposed the violent underpinnings of British capitalism and the resolute will of indigenous resistance (Falola & Heaton, 2020).

10.2.2 The Benin Massacre and Punitive Expedition (1897)

In 1897, British officials attempted to enter Benin City during a sacred festival, violating protocols. Their ambush by Benin warriors led to a full-scale British military response.

The Benin Punitive Expedition saw the British invade, burn, and loot the ancient city, exile Oba Ovonramwen, and steal thousands of artefacts—the Benin Bronzes, now symbols of colonial theft and cultural vandalism.

This assault was not just territorial—it was psychological and cultural subjugation. Yet, the sophistication of Benin’s pre-colonial civilization, revealed through its resistance and artistry, later became a touchstone for nationalist pride (Hicks, 2020).

10.2.3 The Ekumeku Movement (1898–1914)

Among the Anioma people of Western Igboland, a decentralized network of guerrilla fighters—the Ekumeku Movement—formed in response to British attempts at annexation and taxation.

Operating from the forests, the group launched surprise attacks on colonial outposts, destroyed infrastructure, and engaged in long-term resistance. Despite brutal suppression campaigns—including mass executions and scorched-earth tactics—the movement persisted for over 16 years.

British officials labelled Ekumeku “terrorist,” but local oral traditions celebrate it as a heroic struggle for self-rule and cultural survival. The movement’s resilience laid ideological groundwork for future resistance formations.

10.3 Women’s Resistance: The Aba Women’s War (1929)

Often overlooked in male-dominated histories, women played a central role in anti-colonial resistance. The most iconic example is the Aba Women’s War—a mass uprising in 1929 by thousands of Igbo women against British-imposed taxation and administrative overreach.

The root causes of the revolt were:

- The imposition of direct taxation on women, seen as a gross violation of Igbo gender norms.

- The increasing corruption and abuse of warrant chiefs, colonial appointees with no traditional legitimacy.

- Broader economic hardship and the erosion of women’s political power in village assemblies.

Beginning in Aba and spreading to surrounding areas, the protests involved sit-ins, singing, dancing, and occupation of colonial courts. Women used cultural idioms and protest songs to denounce colonial authorities and demand justice.

The British response was violent. Troops opened fire on unarmed women in multiple locations, killing over 50 protesters and wounding many more (Chuku, 2021).

Despite the tragedy, the movement forced the colonial government to reassess direct taxation, dismiss many warrant chiefs, and reform local governance. The Aba Women’s War remains one of the earliest mass women-led anti-colonial uprisings in Africa.

10.4 Rise of Early Nationalist Thinkers

The early 20th century witnessed the emergence of nationalist intellectuals who used writing, activism, and legal action to challenge British imperialism. These figures laid the ideological foundation for Nigeria’s eventual independence.

Herbert Macaulay (1864–1946)

Often referred to as the Father of Nigerian Nationalism, Macaulay was a civil engineer, journalist, and political agitator. He founded the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP) in 1923 and used his paper, The Lagos Daily News, to criticize colonial injustices.

Macaulay championed:

- Legal defense for marginalized Nigerians

- Protests against land seizures

- Advocacy for indigenous governance

As Adewale (2023) notes, Macaulay bridged the gap between elite Lagos politics and grassroots agitation, becoming the first public figure to articulate a Nigerian political identity.

Nnamdi Azikiwe (1904–1996)

Educated in the United States., Azikiwe returned to Nigeria in the 1930s, launching The West African Pilot newspaper and quickly becoming a symbol of Pan-African resistance. His ideology combined national self-determination with continental solidarity.

Azikiwe:

- Criticized colonial racism and economic exploitation

- Promoted mass literacy and political mobilization

- Founded the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) in 1944

His emphasis on unity, mass mobilization, and federalism made him a central figure in the independence movement.

Obafemi Awolowo (1909–1987)

Leader of the Action Group (AG), Awolowo was a visionary who pushed for:

- Free primary education

- Regional autonomy

- Economic self-reliance

Though often regional in base (Southwest/Yoruba areas), Awolowo’s governance in Western Nigeria demonstrated that nationalist rhetoric could translate into developmental policy (Osaghae, 2021).